- Home

- Mark Lawrence

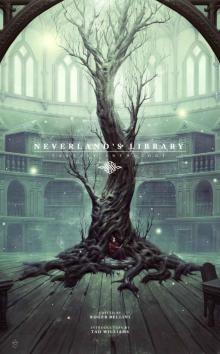

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Page 21

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Page 21

Unless it was some sort of trap to make our punishment even worse, our father was giving us a means of escape. But while I groped for an answer, Soff didn’t. “Break our hands, father. Not both. I mean both of us, but not both our hands. Just our off-hands. That way we can still be useful.”

If I was stunned by the question I was even more stunned by the answer. Break our hands? Was the girl mad? I wanted to hit her, tackle her, choke her. But then my father turned to me. “And what of you, Bray? Do you agree with your sister?”

I felt like I was swallowing hot sand, like the distances in the room shifted and my father and his question were very far away. It wasn’t him who trapped us, but my sister, the one who initiated the idea, the one who planned out each robbery, who challenged my manhood, goading me into going each time. And here she was challenging me again. If I suggested a lesser punishment, I would be less than a girl, a cretin, the lowest of the low.

Hating her, I sucked down the sand and nodded once. My father nodded too, as did my mother, and for the briefest second I thought I saw the corners of her lips lift, but then it was gone. My uncle, however, didn’t nod, and certainly didn’t smile. He glared at my father, and though he didn’t spit, I’m sure he wanted to. “No. It isn’t enough. They broke into our father’s grave, brother. A chieftain. It isn’t enough.”

Our father patted our cheeks and dropped his hands to his sides. “They understand what they've done. They understand how they must pay.”

Sirk opened his belt pouch and pulled out the torc and cloak clasp he’d seized from us. “They stole for profit, Findarr. Profit. Bad enough if they were just jealous of his accomplishments, his possessions. Few don’t covet from a chieftain. But they wanted only coin.”

Our father looked at us and asked, “Is this true, children? Did you steal these things to sell them?”

Before Soff could make it worse, I replied, “No, father.”

My father crossed his arms in front of his chest and looked at our uncle. “The punishment matches the crime, Sirk. I’ve made my decision.”

Sirk’s lip curled. “They lie. But it doesn’t matter. This isn’t your decision to make. It’s ours, Findarr. Ours. All descendants must agree on the punishment, and I don’t.”

“They are my children,” my father said. “And I’ve spoken on this matter. If you had children, you might understand. But—” Sirk gave my father a withering look, slid the sword in his belt, and then disappeared through the deerflap.

Our mother tucked a strand of hair behind her ear, looked at my sister’s face and then mine. She opened her mouth, shut it, and opened it again, “I’m ashamed of what you’ve done. But proud you didn’t run from it. Now go to bed.” And so we did, heading to our pallets for a sleepless night.

#

The hours passed slowly, and despite the chill in the air, my pallet was a mess of fur, sweat, and spindly limbs. I changed positions a hundred times, each worse than the last. I was finally closing in on exhausted sleep when I saw Soff sit upright on her pallet, arms braced behind her. I was happy to see her tunic as sweat-stained as mine, but nervous about her expression.

“What’s going on?”

She didn’t look back at me. “It’s Sirk. He’s come back.”

I listened. Voices, angry from the sound of it, although they were some distance from the longhouse.

Soff stood, slipped into her trousers, threw a belt around her waist, pulled her hair out of her eyes and knotted it behind her head. “Get up and get dressed.”

“What? Why? I don’t—”

“Just do it,” she said. “They’ll be back in a few minutes. It’s impossible to be strong crouched and naked. Now get up.”

“For what? Strong for what? Are they…” I had difficulty saying it. “Are they going to do it, now? Break our hands?”

Soff walked over and pulled me to my feet. “Worse.”

“Worse? Than breaking our hands? How worse? What’s—?”

“They’re taking us to the grove, Bray.”

I stepped into my trousers, cringed as they slid across the welts on the back of my legs. My words felt small and so did I. “I don’t understand.”

Soff wrapped a belt around my waist and buckled it. “Of course you do. Uncle called for a Reckoning. And unless I mislistened or someone was lying, it’s about to start.”

I would’ve fallen back on the pallet if she hadn’t been holding my shoulders. “But last night, father said he decided, you were there—”

“The priests don’t see it that way. Now splash some water on your face and comb the hair out of your eyes.” She gave me one of her rare smiles. “It's also easier to be strong when you can see who your enemies and allies are.”

And so I readied myself as best I could and sat at our table. Soff brought me a hunk of dry bread, a small bowl of honey, and a clay jug of goat milk. I protested, but she pushed the food on me. “Eat.”

It wasn't long before we heard our parents enter the adjoining room. My sister had time to wipe some milk off my face and tell me to stand tall, and then the flap opened and they stepped through. My father looked at us both, looking weary. “Your uncle Sirk, he—”

“We know,” Soff said. “We heard you outside. Or I did. We know about the Reckoning.”

Under any normal circumstances, my mother would’ve berated Soff for interrupting. Instead, she said, flatly, “Do you?”

“Yes,” Soff said. “And we’re ready.”

My father nodded again. “Good. Because the priests are ready for you. But before we go, I want you to know something—your uncle is no less fierce than his father before him. Fierce in love, fierce in vengeance. And it’s only his fierce love of his father prompting this. Nothing else. Remember that.”

Our father led us out of the longhouse, into the cold gray daylight. The village was deserted, as we expected. Everyone was at the grove, waiting. Our parents leading, we walked over small wooded hills, oak trees rising high above us, an ageless trail and our breath before us. Autumn and winter fought for possession of the land and leaves crunched beneath our feet. The Reckoning site wasn’t far, a clearing carved out of a grove of birch alongside a small river, and it wasn’t long before we could hear the gurgle of rushing water.

The site had been used as far back as any skald could remember, and had never changed. Or hadn’t, until the summer before the graverobbing. As we made our way through the tall, peely birch, the change wasn’t immediately obvious. First one tree, toppled, as if blown over by wind, its white bark flaking off in huge ragged chunks. And then another, much further along on the path, on the opposite side. Nothing truly peculiar. Trees die, and fall when they do. But the closer we got to the river, the more trees we saw on the ground. Two dead birch laying across each other on the right, trunks rotted, and more on the left, increasing until the dead outnumbered the living. What had once been a small clearing in a tightly knit forest was now a vast opening, littered with trees poisoned by some unseen thing.

Stones and logs served as seats at the outskirts of the clearing, all occupied. Our uncle was standing with the river at his back, flanked by our three priests garbed in furs and the drab colors of the deep forest. Grubarr, the Earth Priest, was a short, hairy man, head as bald as a stone, big-bellied, big bearded, his mustache covering all but the bottom of his bottom lip. Another, taller and of middling weight, but pale, beardless, and ill-looking, a Moon Priest, called Throp to his face, Milkthrop behind his back. And last, Sun Priest Hrodomin. Impossibly tall, impossibly severe Hrodomin. Though Grubarr was the grayest of the three, Hrodomin’s bark face and rooty hands attested to his years. But he still had a voice like a slide down a gravel pit, deeper and rougher with each word, and a legendary temper.

Hrodomin saw us at the edge of the grove and with one clap of his gnarled hands conversation ceased. People began looking over their shoulders and spinning on the stones to find us.

Hrodomin waited for us to enter the circle and then spoke to all atte

nding, “A Reckoning has been called, a Reckoning must be had.” The other priests echoed him and he continued. “We’re here today to decide the punishment of Soffjan and Braylar, children of Findarr and Morlen. Though they were caught in the middle of their crime, their punishment is in dispute. It will be settled today. So says the tribe, so say the priests.” Again he was echoed.

Hrodomin raised a hand, his sleeve falling down his sinewy arm. “Soffjan, Braylar, step forward.” All eyes were on us, a mixture of scorn, disapproval, and curiosity.

As we came closer, I wanted to look away, at the ground, the dying birch, the sunless sky, but a Reckoning is a tricky business—to stare defiantly at the priests was to risk their wrath, but to avoid their gaze entirely was to show disrespect and cowardice. I looked at Soff and sure enough, her head was high and she was staring directly at them, the only sign of discomfort a few blinks to free her long lashes. It seemed she was determined to make this as bad for us as possible. I thought if I looked at my shoes penitently we might balance out, but when Hrodomin cleared his throat to speak I found myself looking up anyway, into a face craggier than our mountains.

He said, “You swear upon the gods you’ll speak nothing but the truth, today and forever.”

We nodded. Hrodomin didn’t continue. It was Soff who remembered the next part, saying, “Today and forever.” It took me a second before realizing I was required to say it as well and did.

Hrodomin said, “Last night you were discovered disturbing the grave of your grandfather. Is this true?”

Soff replied, “This is true,” and after a moment I parroted.

“Your uncle Sirk was the one who discovered you. Is this true?”

A duet of “This is true.”

“Sirk claims you were not vandalizing, but opened the grave to loot it. Is this true?” Neither of us spoke. “Let me remind you, Soffjan and Braylar, you swore before your priests, your kin, your ancestors, and the gods. Let me also remind you that refusing to reply is the same as a lie. Now, do you freely admit you broke into the tomb to loot it?”

Before I could stop myself I said, “Not freely.”

Soff elbowed me in the ribs and there were a few laughs behind me but Hrodomin clapped twice, demanded silence, and got it.

He took a step towards me, towering even more. “What did you say?”

I licked my lips but held my tongue. Hrodomin bent at the waist, his mixed beard of white and black dangling in front of my face, his breath like the air in a dark, dank place a dying animal might choose to hide in. “Speak, son of Findarr.”

“I said… I said not freely.”

He raised a hoary eyebrow. “Meaning?”

“Well… “ I looked at my sister and then at my uncle standing alongside the other priests. He still had our grandfather’s sword in his belt, one hand resting on the pommel. “You said to speak the truth, and that’s the truth. We don’t admit to looting. Freely. If we had a choice I’m sure we wouldn’t be here at all.”

“Ah. I see.” Hrodomin rose back up, turned and walked back to the center. “Let it be known Hrodomin, Sun Priest of the Tribe Vorlu, misspoke in asking the question.” There were some chuckles around the grove. He faced us once more. “Let me try again. You broke into the tomb to loot it, to sell what you found. Is this true?”

I was afraid my mouth might betray me again, so I kept it shut, but Soff had no such reservations. “Yes. I mean, this is true. We did.”

“But you told your family something different last night.” He paused and then looked directly at me. “Is this true?”

Soff looked at me too, along with everyone else. Afraid my voice might squeak, I simply nodded.

Hrodomin waited, apparently dissatisfied. Very quietly, I said, “This is true,” and immediately began wondering why my sister insisted on telling the truth when it clearly wasn’t helping us.

Hrodomin continued, “So, it seems you’re liars as well as thieves.” Soff started to object but Hrodomin overrode her, hand raised, palm out. “That wasn’t a question.” She shut her mouth more quickly than I believed possible. “Liars and thieves prove to be very poor witnesses. Especially in their own trials. Which leads me to believe asking more questions of you is a waste of this council’s time, oath or no oath.” He crossed his arms in front of his chest. “Before I’m done with you though, I have one final question: you could’ve chosen any grave to rob, and yet you chose not only kin, but one who was a respected chieftain as well. Why?”

I looked at Soff, since the plan was hers, but she was silent. Hrodomin approached us again, but this time addressed her. “Your brother is better at ‘this-is-true’ questions, but seeing as how he’s younger, I’m sure he looks to you for guidance. There are many tombs in these hills, and you could have chosen any of them, yet you picked your grandfather’s.” He stood directly in front of her. “You would be wise to tell me why.”

I was afraid she might be possessed by another fit of damning honesty, admitting to the previous graverobbings, but she didn’t. Instead, she said, “His was the finest tomb we knew of. I thought so long as we were going to steal, we might as well steal big.”

Hrodomin’s wrinkled face somehow grew more wrinkled with anger. “Do you have anything further to add before I dismiss you, daughter of Morlen?”

I hoped she wouldn’t. Foolishly. “I understand what we did is considered wrong,” she said. “I’m sorry for having been caught, but I’m more sorry for any pain I’ve caused my kin.” She looked at our father briefly and then back to Hrodomin. Never one to know when to bite her tongue, she added, “But I’m also sorry to see such fine things left in the ground to rot. Seems a shame to bury it all, tradition or no. That’s it. That’s all.”

Hrodomin waved his hand in dismissal to both of us, but it was evident on his face that wasn’t quite the sentiment he has expecting to hear. He stepped back and rejoined the other priests; they conferred quietly for a moment and then gray Grubarr spoke, “Come forward, Findarr, son of Drogan.”

Our father walked a few steps closer to the trio of priests. I wondered if he was relieved. Where Hrodomin embodied menace and intimidation, Grubarr was a study in detachment. Amused detachment. Disconcerting in its own way, but still better than Hrodomin.

Grubarr blew on his hands and rubbed them together. “Findarr, your brother tells us you decided upon a punishment for your misbehaving brood, but he…disagreed with you. Tell me more of this.”

Though it was cold, my father was sweating, but he still managed to smile as he glanced in our direction. “After explaining the severity of the crime, I asked my children what they thought would be a proper punishment. I was satisfied with their answer.”

Grubarr seemed interested, although only mildly. “Their answer?”

“Soffjan suggested we break one of their hands. Braylar agreed.”

Grubarr looked at us briefly, quizzically perhaps, then back to our father. “Hmm. A moment ago, this daughter of yours didn’t sound so…penitent. Most impenitent, in fact. What do you make of this?”

Our father replied, “She’s a headstrong girl, stubborn to a fault. Braylar is little better. But when confronted last night they showed more courage than I would have at their age. Maybe any age. I would have suggested a less harsh punishment than what they came up with themselves.”

Grubarr didn’t appear wholly convinced or unconvinced, still looking at us curiously. “Hmm.” He licked his fingers, played with his mustache, and said, “But your brother, he felt… differently?”

“Yes. He did.”

Grubarr tapped his chin, licked his finger, and then said, “Very good, Findarr, father of strange thieves. Thank you.”

Our father rejoined our mother, Grubarr rejoined Hrodomin, and then it was Throp’s turn to speak. Though Milkthrop often had the pale face and shaky demeanor of someone who just vomited, he took his office seriously and intoned with a great deal of vigor. “Sirk, son of Drogan, step forward and be recognized.”

; Sirk stepped forward, one hand on the hilt of his father’s sword. Milkthrop pointed at our father as if Sirk might have forgotten his identity in the last few minutes, and said, “You have heard your brother on this matter. Do his words sound ill-forged to you?”

The season’s first snowfall began with his words, heavy, wet flakes falling straight down. Sirk replied, “Not ill-forged, Moon Priest. But there’s strong metal and there's weak.”

“Meaning?”

“All here know how he responded when our father died. He didn’t side with Drunik. He didn’t side with me. Fine. But he didn't even side with himself. He stayed out of the conflict. That’s his way. Avoid a problem, avoid a fight, avoid anything demanding something of him. Weak.”

My father’s face tightened with these words, but his turn to speak had come and gone, and he couldn’t really offer any evidence to the contrary.

Sirk continued. “The same holds true with his children. Over-indulgent. If he could avoid punishing them at all in this matter he would. A few stiff words would be all. But he can’t. I won’t let him. And you won’t let him.”

“Don’t presume to know the mind of this council, Sirk.”

Had these words come from Hrodomin, he might have let them go, but Sirk replied, “We’re here to see justice done, are we not?”

Milkthrop raised a finger, as if admonishing a child. “We are indeed. And we will see it done. We. Your purpose here is solely to supply information. In calling for this Reckoning you relinquished your right to determine punishment. You would do well to remember that.”

Sirk looked ready to choke but slowly forced himself to reply, “As you say.”

Milkthrop said, “You believe your brother weak and indulgent. This much you’ve said. And this council might be inclined to agree if he hadn’t suggested such a punishment. But—”

“He didn’t suggest it, his children did.”

“Fine. But does the origin make it any less substantial or appropriate?”

Sirk pulled his father’s blade from his belt and Milkthrop took two quick steps back, nearly tripping over himself. “Need I remind this council who this belongs to? Alive it was his; dead, just the same.” He spun around and addressed the crowd. “He’s ten years in the ground, but there isn’t a person among you,” he looked directly at us, “save stupid children, who don’t remember him well. My father was a hard and powerful man, respected if not always loved, but he did what no one has done since Hrolan. Unified the mountain tribes. I challenge any of you to name a more revered chieftain in living memory.”

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology