- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Read online

Vodka Politics

VODKA POLITICS

Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

MARK LAWRENCE SCHRAD

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

© Oxford University Press 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–199–75559–2

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For my wife, Jennifer.

I have so many words to express so many things, but none could hope to describe my love and appreciation for who you are and all you do.

CONTENTS

Note on Proper Names

Preface

1. Introduction

2. Vodka Politics

3. Cruel Liquor: Ivan the Terrible and Alcohol in the Muscovite Court

4. Peter the Great: Modernization and Intoxication

5. Russia’s Empresses: Power, Conspiracy, and Vodka

6. Murder, Intrigue, and the Mysterious Origins of Vodka

7. Why Vodka? Russian Statecraft and the Origins of Addiction

8. Vodka and the Origins of Corruption in Russia

9. Vodka Domination, Vodka Resistance … Vodka Emancipation?

10. The Pen, the Sword, and the Bottle

11. Drunk at the Front: Alcohol and the Imperial Russian Army

12. Nicholas the Drunk, Nicholas the Sober

13. Did Prohibition Cause the Russian Revolution?

14. Vodka Communism

15. Industrialization, Collectivization, Alcoholization

16. Vodka and Dissent in the Soviet Union

17. Gorbachev and the (Vodka) Politics of Reform

18. Did Alcohol Make the Soviets Collapse?

19. The Bottle and Boris Yeltsin

20. Alcohol and the Demodernization of Russia

21. The Russian Cross

22. The Rise and Fall of Putin’s Champion

23. Medvedev against History

24. An End to Vodka Politics?

Notes

Index

NOTE ON PROPER NAMES

In this book, Russian names generally follow the British standard (BGN/PCGN) transliteration, with some alterations to accommodate the widely accepted English equivalents of familiar historical figures (for example, Tsar Nicholas and Tsarina Catherine, rather than Tsar Nikolai and Tsaritsa Ekaterina). To aid pronunciation, I have opted to change the Russian “ii” ending to a “y,” and eliminate the Russian soft sign from personal and place names (so Maksim Gor’kii becomes Maxim Gorky). These alterations do not apply to the bibliographic references in the notes, which maintain the standard transliteration for those who wish to consult the original sources.

PREFACE

A book about Russia based on vodka? How’s that going to sit with Russian readers? Well, when a New York Times article I wrote related to the subject found its way onto the Russian-language blogosphere, it certainly didn’t take me long to find out: “Vodka? Hey, while you’re at it, don’t forget the bears and balalaikas” came one understandable rejoinder, drenched in the requisite sarcasm about gullible foreigners and their misguided perceptions about Russia. Dozens more jibes and sneers quickly followed.1

To be sure, confronting well-worn clichés is an uncomfortable business. Especially when unflattering broadsides are made against an entire nation, they prompt a response from both those outside and inside the group such stereotypes purport to describe. For insiders, the usual response to a hurtful platitude is to downplay or deny it. Sympathetic outsiders normally try to politely ignore it. Rarely do offended parties embrace a perceived insult, and rarer still does anyone stop to investigate and explore it.

Obviously, in studying Russia—its people, culture, politics, and history—we encounter just such a widely held and uncomfortable stereotype in the form of the hopelessly drunken Russian. People who can barely locate Russia on a map readily associate it with insobriety, while foreigners studying the Russian language surely know how to say “vodka” well before they even learn to say “hello.”

Yet that image is not exclusive to foreigners: as the new millennium dawned, the All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion (VTsIOM) asked actual Russian citizens what they considered the main symbol of twentieth-century Russia: vodka beat out not just bears and balalaikas, but also nesting dolls and even AK-47s for the top spot.2 When it comes to perceived challenges for Russia’s future, such concerns as “national security,” “economic crisis,” and “human rights” are routinely listed as national threats only by some ten percent of VTsIOM poll respondents. “Terrorism” and “crime” are consistently named around twenty-five to thirty percent of the time. The challenge that usually claims the top spot as Russia’s most pressing challenge is “alcohol and drug addiction”—voiced by some fifty to sixty percent of respondents, year in and year out.3 Still, while everyone knows alcohol is a major social problem, vodka’s roots run so deep in Russian history and culture that simply acknowledging—much less unpacking and confronting—this endemic challenge seems somehow impolite, especially for an outsider.

Yet while virtually every developed country on earth put their so-called liquor question to bed a century ago, alcohol continues to bedevil high politics in Russia. For instance, in late 2011 and 2012, an unprecedented wave of popular opposition in Moscow nearly thwarted Vladimir Putin’s return to a third term as Russia’s president following four years as prime minister alongside his protégé Dmitry Medvedev. In his last major speech to the Duma—the lower house of Russia’s parliament—before his re-inauguration, Putin highlighted Russia’s precarious health and demographic situation as one of his administration’s most pressing political challenges. “Without any wars or calamities,” Putin said, “smoking, alcohol, and drug abuse [alone] claim 500,000 lives of our countrymen every year. This is simply a horrific figure.” Unless Putin suffers from amnesia, these indeed-horrific figures should not have come as any surprise: he repeatedly lamented vodka’s ghastly toll during both his first and second administrations (2000–2008) in almo

st the same language.4

Since Putin emerged on the political scene in 1999, Russian social indicators have unquestionably improved upon the unimaginable social devastation and economic demodernization in the years immediately following communism’s collapse in 1991. The economy grew at some seven percent per year for an entire decade from 1998 to 2008 before getting hammered by the global financial crisis. Yet while the macroeconomic indicators were on the rebound, figures on Russian life expectancy more closely resembled sub-Saharan Africa than postindustrial Europe. Even today, the average teenage Russian boy has a worse chance of living to age sixty-five than do boys in failed states like Somalia and Ethiopia.5 But unlike these desperate places, it isn’t malnourishment or famine that is to blame—nor is it the errant bullets of civil war: it is vodka, pure and simple. With Russians consuming on average eighteen liters of pure alcohol per year—or more than twice the maximum amount deemed safe by the World Health Organization—in 2009 then-president Dmitry Medvedev called alcohol a “national disaster,” ushering in a new attempt to combat the eternal Russian vice.6

Russia’s tragic cultural weakness for vodka is often chalked up to the torments of the “Russian soul.” But simply assuming that intoxication and self-destruction are somehow inherent cultural traits—unalienable parts of what it is to be Russian, almost down to the genetic level—is akin to blaming the victim. There is nothing natural about Russia’s vodka disaster.

As I argue here, Russian society’s longstanding attachment to the vodka bottle—and the misfortune that follows in its wake—is instead a political disaster generated by the modern, autocratic Russian state. Before the rise of the modern Russian autocracy, the people of medieval Rus’ drank beers and ales naturally fermented from grains, plus meads naturally fermented from honey, and kvas naturally fermented from bread. If they were well-to-do, they imported wines fermented from grapes and berries. They not only drank beverages similar to those elsewhere on the European continent; they also imbibed similar amounts and in a similar manner. That all changed with the introduction of the very unnatural process of distillation, which created spirits and vodkas of a potency—and profitability—that nature simply could not match. Beginning in the sixteenth century, the grand princes and tsars of Muscovy monopolized the lucrative vodka trade, quickly promoting it as the primary means of extracting money and resources from their lowly subjects.

The state’s subjugation of society through alcohol was not unique to Russia: even into the nineteenth century distilled spirits were instrumental in “proletarianizing” colonial Africa and subjugating the slaves of the antebellum United States—but nowhere did alcohol become a more intractable part of the state’s financial and political dominance over society than in Russia’s autocratic tsarist and Soviet empires, which has left disturbing legacies for the present and future of today’s Russian Federation.7 The moral, social, and health decay that resulted from plying the people with copious amounts of vodka could be easily overlooked so long as the treasury was flush and the state was strong. That the people’s misery led them back to the tavern rather than forward to the picket line was an added benefit, at least as far as the stability of the autocratic leadership was concerned. In sum: vodka is only as natural as autocracy is natural—in Russia, they are woven together as part of the same cloth.

Does this mean that vodka is everything in Russia? Certainly not, but it is a lot of things. I don’t claim to offer a monocausal explanation of Russian history: it would be the height of foolishness to claim that everything of political significance can be explained with reference to alcohol. Instead, I present vodka politics as an alternative lens through which to view and thereby understand Russia’s complex political development. Think of it as beer goggles for Russian history—but unlike beer goggles that distort our perceptions, viewing history through the lens of vodka politics actually brings things into clearer focus. Vodka politics helps us to understand the temperament of Russia’s famed autocratic leaders from both the distant and not-so-distant past and how they relate to their subjects. It highlights the significance of previously overlooked factors in major events in world history, including wars, coups, and revolutions. It fills in significant gaps in our understanding of politics and economics with Russian society and culture. It gives us new appreciation for the greatest works of Russian literature and casts stale understandings of Russia’s internal dynamics in a completely new light. Finally, it may just help us confront the monumental challenges that these historical legacies of autocratic vodka politics present for a healthy, prosperous, and democratic future.

The Russian people today understand that they confront a huge problem with alcohol, and leaders across the political spectrum also begrudgingly admit that vodka is—quite possibly—the most serious problem facing their country. With so much to be gained in terms of both understanding the past and confronting the future, the benefits of addressing alcohol in Russia rationally and seriously far outweigh the risk of ruffling feathers and confronting a sensitive and uncomfortable stereotype or politely dismissing the topic as somehow too cliché. Scholars of all stripes and nationalities have done that for far too long already.

This surely isn’t the first biography of vodka, nor will it be the last. Russians have been writing national histories of alcohol dating from Ivan Pryzhov’s Istoriya kabakov v Rossii (History of Taverns in Russia) as early as 1868. Much of the subsequent popular literature on the topic—both in Russia and abroad—examines both the evolution and etymology of the drink we now know as vodka and tends to be rather superficial.8 Far more rewarding are the works of professional historians, political scientists, sociologists, anthropologists, demographers, and public health experts who have dedicated their academic careers to understanding narrow slices related to the general history of alcohol in Russia. These include David Christian’s Living Water (1990) dealing with the pre-emancipation Russian empire, Patricia Herlihy’s Alcoholic Empire (2002) on late-imperial Russia, Kate Transchel’s Under the Influence (2006) on the tumultuous years of communist revolution, Vlad Treml’s Alcohol in the USSR (1982) on the postwar era, Stephen White’s Russia Goes Dry (1996) on Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign, or Aleksandr Nemtsov’s Contemporary History of Alcohol in Russia (2011) on the Soviet and post-Soviet legacies.9 Unlike the more cursory social histories of vodka, I have built upon these and other more rigorous academic investigations—as well as unearthed additional primary source materials, including those in Russian, European, and American archives—to instead paint a political biography of alcohol in Russia by investigating how vodka is intimately tied to Russian statecraft across historical time periods: from Ivan the Terrible through the 2012 elections and beyond.

This book is neither meant to valorize alcohol nor maliciously lampoon Russian drunkenness. It is not an exercise in patronizing orientalism or anti-Russian hysterics—it is a recognition of the variety of ways alcohol influences and catalyzes political phenomena (and vice versa) in the context of Russian history. Even the idea of a political biography of alcohol is not unique to Russia. Indeed, W. J. Rorabaugh’s influential Alcoholic Republic (1979) similarly recast the early history of the United States in a new light: America was widely considered “a nation of drunkards” in the period when anti-British revolutionary plots were being hatched in smoke-filled taverns. Even as early as the 1730s the most successful newspaper in the American colonies, the Pennsylvania Gazette, compiled a list of 220 colloquialisms for being drunk and also ran reports of foreign attempts to deal with rampant drunkenness. The author of such pieces was none other than the young Philadelphia printer and future founding father Benjamin Franklin. Actually, most of America’s vaunted founding fathers had ties to alcohol, as winemakers, brewers, or distillers, with whiskey distiller George Washington even becoming the iconic leader of the new country.10 Yet while every country has its own history with alcohol, perhaps in no other country is that relationship as enduring and intertwined with the culture, society, and politics of the

nation than in Russia. In the end, I hope that this book will instill in others the same adoration and fascination with Russia—its people, politics, history, and culture—that has motivated me for the past twenty years.

The writing of the manuscript occupied only the last three of those years—though it seemed like far longer than that. For too long this project has taken me away from my loving wife, Jennifer, and my children, Alexander, Sophia, and Helena. I’m looking forward to baseball games, swimming lessons, and bike rides with my family—all of which were put on hold for this book. My parents, Dale and Paula Schrad, were always willing to bail me out on the home front when the writing needed a kick-start, while my brothers Dan and Kent were ready with sagacious advice and support. This project would be nothing without my family—and neither would I, for that matter.

I’m also indebted to friends, colleagues, administrators, and students at Villanova University—especially in political science and Russian studies—who have provided feedback, camaraderie, and a wonderful and inclusive environment for our family. In particular, I benefitted tremendously from discussions with Lynne Hartnett, Adele Lindenmeyr, Jeffrey Hahn, Matt Kerbel, Christine Palus, Markus Kreuzer, Father Joe Loya, Miron Wolnicki, Boris Briker, Lauren Miltenberger, David Barrett, Kunle Olowabi, Lowell Gustafson, Jack Johannes, Bob Langran, Eric Lomazoff, Catherine Warrick, Catherine Wilson, Lara Brown, Maria Toyoda, Jennifer Dixon, Daniel Mark, Shigehiro Suzuki, and Mary Beth Simmons. Meanwhile, good friends Erasmus and Maureen Kersting were always there to listen to my frustrations and gripes, even after hours. While Father Peter Donohue, Father Kail Ellis, Merrill Stein and Taras Ortynsky provided institutional support at different administrative levels, Steven Darbes, Shishav Parajuli, and Max McGuire were instrumental for their research assistance. Villanova University also provided a much-appreciated subvention to secure licensing for the various photos used throughout the book. Yet more than anyone at Villanova I owe a deep debt of gratitude to Steven Schultz, who diligently poured over chapter upon chapter, draft upon draft—talking me through so many unexpected frustrations of writing for a wider audience. Thank you.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

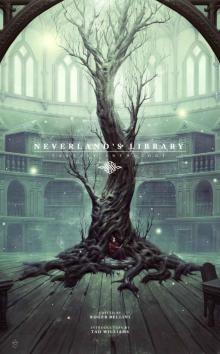

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology