- Home

- Mark Lawrence

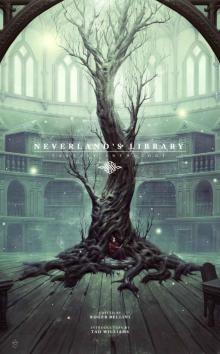

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Neverland’s Library

Copyright © 2014

Edited by Roger Bellini with assistance by Tim Marquitz

Edits provided on select stories by Rebecca Lovatt

Cover Art by Gabriel Verdon | Interior Art by Tom Brown

Stories and artwork copyright © 2014 their respective creators. All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Worldwide Rights

Created in the United States of America

Published by Ragnarok Publications | www.ragnarokpub.com

Editor-In-Chief: Tim Marquitz | Creative Director: J.M. Martin

Neverland’s Library

Roger would like to thank:

All the supporters and authors. Thank you for believing in the idea and answering the call to make a dream come true. Truly, it means the world to me.

Thanks to Ragnarok Publications for being willing to take the reins.

Table of Contents

Introduction – Tad Williams

Deception – Mark Lawrence

Shadow Dust – J.M. Martin

Dead Ox Falls - Brian Staveley

Redemption at Knife’s Edge – Tim Marquitz

A Soul in Hand – Marsheila Rockwell and Jeffrey Mariotte

The Machine – Kenny Soward

Season of the Soulless – Betsy Dornbusch

Redfern’s Slipper – Stephen McQuiggan

Fire Walker – Keith Gouveia

The Height of Our Fathers – Jeff Salyards

The Last Magician – William Meikle

Restoring the Magic – Ian Creasey

Charlotte and the Demon Who Swam Through the Grass – Mercedes M. Yardley

On the Far Side of the Apocalypse – Peter Rawlik

The Stump and the Spire – Joseph Lallo

Love, Crystal, and Stone – Teresa Frohock

A Tune from Long, Long Ago – Don Webb

An Equity in Dust – R.S. Belcher

Centuries of Kings – Marie Brennan

Renaissance – Miles Cameron

About the Authors

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

Finding Fantasy, Again.

THE FIRST TIME one of our cave-dwelling ancestors came back scratched up and bleeding from a rough day of hunting or gathering and someone asked, “What happened?” literature was born. But the first time someone painted something on a cave wall that nobody else recognized, and explained it by saying, “I saw it in a dream” –well, that was the birth of fantasy.

For a very long time in human history there wasn't much difference between what we experienced and what we imagined. When blind Homer was reciting his poems about the Trojan War, did he think his semi-historical warriors like Achilles and Hector were more “real” than the gods who stand behind every scene in The Iliad? That's a hard question to answer even today, when we call the creations of our mind “imagination,” and wall them off in a separate category from Truth. But what we see when we look at another human being is still only the tip of a great iceberg. What is in that human's head is a lot bigger and a lot stranger than the physical reality. We used to know that better than we do now.

What we experience. What we imagine. For a long time the two were pretty much equal in importance. There were witches in our villages, monsters in the forest, and dragons at the edges of the maps.

The growth of Reason, a belief that the universe could be understood by sheer hard work, drove the first wedge between these two types of reality. You may have noticed that a great deal of fantasy writing takes place in pre-industrial settings. That's because it's not the trappings of industry that discourage fantasy (Steampunk does very well in that world) but the growth of understanding. Reason spawned science fiction, a literature of human doings and human interaction with a bigger universe, stories based on ideas that seemed as if they might be possible one day. Humans (some of them, anyway) began to believe that everything we saw and heard and touched might be part of a larger, logical system, that we might understand everything if we could only tease out the truth.

Fantasy, though, is a literature of things beyond explanation. It calls us back to childhood, either the childhood of our species, before we knew those map-dragons were imaginary, or our own individual childhoods, when shadows held scary stuff, when things lived under our beds and in our closets or in that one part of our journey home where we had to walk through the dark woods.

The title of this anthology, “Neverland's Library,” comes from Peter Pan, a famous story about not growing up—about continuing to see the world as children see it. We live in this modern age with a conflicting but ever-growing set of logical explanations for almost everything, for rainbows and eggs and evil. If somebody does something horrible beyond our understanding, we don't just assume that person been possessed by a demon or touched by malign gods, we try to track the genes and influences that created the monster, to find out where everything went wrong.

But the childlike part of us will never be entirely satisfied with this modern world of reasons and explanations and facts. The child in all of us, the part of us that used to paint dreams on cave walls because dreams were just as real as the animals we hunted, still lives in that world, even in this era of instant information and high-definition science. Somewhere, deep down, we still want to believe in gods and monsters, because even if gods and monsters don't explain reality as well as science does, they explain how reality feels.

Good fantasy writing takes us straight back to that important part of us—straight back to the past, straight back to childhood. The darkness beyond the fire becomes meaningful again, and the shadows under the bed are once more dangerous. But—and this is very important—if the danger and darkness are real, then so is the power of bravery, of hope, of simply being good. We don't want an inexplicable universe that's entirely against us, we want an inexplicable universe that might help us, too.

Ultimately, fantasy is about reducing the world to human size again, while expanding what might be to the greatest extent we can imagine. We can do it, because the human imagination is still the single biggest thing there is: it can encompass this entire universe, and several others beside.

Come and join me here, in a human-sized world that is much bigger than the everyday one we know so well. Read these stories. Come visit other places, other times, and other realities that only exist for certain in imagination, and see why we all need more than just “facts.”

Find fantasy. Be in awe again. Be afraid again. Be human.

Tad Williams

September 2013

Deception

Mark Lawrence

“IT WAS THIS BIG!” Jak threw his arms wide. “I swear. I was so close to catching it.”

Dain glanced up from his rock. He lay flat, with his chin over the edge so he could see the water, just two feet below. “Go away. You'll scare off my fish.”

“But I almost caught one,” Jak said. “A lefid. It must have been a

yard long. I—”

“Yes, I believe you,” Dain said. He returned his gaze to the lake.

Jak felt his lip begin to quiver. His brother lay immobile, as though

his tanned flesh were part of the rock.

“I did!” Jak shouted. He felt Dain's accusation like cold fingers reaching into hi

s chest. He turned and ran, following the lakeshore.

The smaller rocks he leapt, the larger ones he scrambled over, careless of the grazes.

The lefid-spear lay where Jak had left it, on his fishing rock. He sat by the spear, hugging knees to chest, no sound but the labor of his breath, the rock warm beneath his feet. The lake spread before him in endless sparkles. I did almost catch it, he thought. It was a yard long. Nearly. I don't lie.

No-one believed Jak these days. Not since he saw the Maker. Not even his older brother. He heaved in a breath, half pant, half sob. He'd been so excited then. So excited that he'd not waited to tell father, but rushed into Chant-Meet and shouted out the news.

“A Maker! I saw a Maker!”

Once more Jak saw the looks the town-folk exchanged. His eyes stung and the sparkles on the lake blurred behind tears. He remembered the people were awkward at first, as if they wished he'd shut up. But then, when he said the Maker was naked, they laughed. They seized on that, and suddenly it was a joke. They could sweep it all away.

I saw him! I didn't dream him.

Priest Roth told Jak he'd dreamed it. Helpless before church orders, Jak's parents had delivered him to the rectory. A slow walk to the dark manse that dominated the town. A servant took him to Roth's study. He remembered the carpet, soft and thick, the crystal glasses in the cabinet, the golden chess pieces, and the priest in contemplation as the servant led him in.

The priest had held him with pinching hands and cold eyes. “You dreamed it, Jakimo. Say it. Say it. If you didn't dream him then you must be lying, and the Makers have fires to burn liars on.”

Sometimes he wondered if it was a dream. The Maker looked so like the stained-glass picture in the Chant-Hall. He could have stepped from that window above the altar-stone. Ten foot tall, overtopped by eagle wings, perfection glowing golden in each limb, hair like spun silver.

Jak sniffed and picked up his lefid-spear. They made us in their image, he thought, but I wish they'd given us their wings too. I'd fly above the clouds and find him again. Make him tell everyone I wasn't lying.

A dark shape flickered by, impossibly large, impossibly fast. The surface of the lake exploded and the first wave took Jak from his rock with a cold slap. Through the spray, he saw stones fly from the beach as the object surged from the water. Several trees fell. Jak heard them splintering. Then silence.

“Jak! Jak!” Dain's voice. His shouts came closer.

Jak tried to answer. He couldn't find his words. The wave had dropped him in a spiny hawthorn to the side of his fishing rock.

“Jak!” The cries held an edge of desperation.

Then Dain was bending over him, dark against the sun, his golden hair a halo. “Thank the Makers! What happened? Are you alright? Can you stand?”

Jak let Dain haul him to his feet, still spilling questions in relief. He wiped the water from his face and shook his brother off. The jagged stump of a pine-oak stood out from tangled undergrowth. The smell of its sap reached him, sharp but somehow sweet. He stepped toward it.

“Jak, don't.” Dain reached for him, but too slow.

As he got closer Jak could see the furrow ploughed up the beach, and the path torn into the trees. He half imagined some giant had thrown a rock from the far shore, falling just short of crossing the lake.

He took another step and almost tripped on a fallen pine-oak. At the broken end, the trunk looked pulverized. The shards dripped crimson. For a moment Jak didn't understand why a tree would bleed. Then he saw the hand. Golden fingers, motionless and curled in the dirt. A fist as big as his head.

“Jak!” Dain called. He seemed very distant.

The brambles cut Jak's hands when he pulled them clear. He didn't feel it. The Maker's eyes were all he saw, gold and molten. It seemed that they only shared a moment, but when Jak turned, Dain was nearly out of sight.

“Dain!” Jak shouted, knowing he wouldn't be heard. “Don't tell them! Don't tell!” But Dain had gone, lost among the beech and elm on the steep slopes up to Cutter Pass.

Jak shouted once more and turned away. He'd wished for proof and now it lay before him. But somehow he didn't want the priest here, or the town-folk, it didn't seem right. And besides, if the Maker left, then Dain would be a liar too.

#

Dain returned with their father and nine other men, including Hender the blacksmith and the elder Priest, Roth.

Roth came first, sweeping the bushes aside with his staff. The brambles caught at his robes and he tore free. Jak could see anger in the set of the priest's mouth and in the thinness of his lips. The others followed with proper deference.

He should be happy, Jak thought.

Jak's father caught him in his arms and swept him up. Dain stood close by, looking at his shoes. Everyone else stopped before the Maker, just staring.

In his hours with the Maker, Jak had no word from him. He'd checked the Maker's injuries. Both wings were shattered in the fall, broken close to the shoulder, stocks of pale bone jutting from torn flesh. The rest of him looked relatively unhurt, no bruises, but deep gashes here and there. The Maker seemed to have no skin, as though he were made from clay, and the blood that filled his wounds was the scarlet of stained glass.

The Maker hadn't spoken to Jak, but he didn't feel ignored. The Maker watched him, and those golden eyes held communion.

Now the Maker spoke.

Into the silence of their amazement he spoke words so deep and fluid that at first they thought it song.

“I have escaped the vaults of heaven to bring you a truth,” the Maker said.

Roth clutched his staff for support. Jak looked at the priest's hands; bony claws on the wood. He remembered the cruelty in their pinching.

The Maker swept his gaze across the men before him. The blacksmith met the Maker's molten eyes, the others looked away. Roth bent his head, then his knee. Jak wondered why the priest scowled so. The others fell to their knees, Ronnan the butcher, then Greyton Jone in his ragged smock. Only Hender remained standing, a smile on his broad face.

At last Roth found his voice. “What is your truth, oh messenger of Heaven?” the priest asked.

The Maker heaved himself into a sitting position. His broken wings trailed through the bushes. Jak found himself wincing, but no trace of discomfort crossed the Maker's face.

“You call me 'Maker', but we did not make you. That is the truth I bring. For this I have broken the Covenant of Heaven, and been cast down,” the Maker said.

Nobody spoke.

“I have set you free. You waste your lives in worship of beings that do not need or want such sacrifice,” the Maker said.

Silence.

Jak spoke. “The Makers didn't say that I must be a farmer? Can I learn my letters? Is it a false law that says I can't read?” He felt it, he felt the chains breaking inside him.

“There is no Maker who has laid such a law,” the Maker said. “We have but one law, and I have broken it. I have spoken with you.”

“No laws?” Jak felt like laughing. He looked up among the dizzying vaults of the forest. Blue sky could be glimpsed above the leaves. “Can we fly?”

The Maker smiled and every nerve in Jak sang. “If you can find a way,” he said.

“You were cast down?” Priest Roth's voice cut across them. He levered himself to his feet. “Thrown from Heaven?”

The Maker nodded.

The priest straightened himself and his face grew hard. “You are Fallen. You are the father of lies. Your sin has denied you grace, and now you try to turn men from the true Makers.

“Look! The Makers have stripped you for your sin and sent you naked to the earth!”

The Maker frowned at this last part, as if puzzled.

“I bring truth,” he said. “A gift.”

Priest Roth stepped forward. He swung his staff and struck the Maker full in the face. The wood broke with a loud crack. The Maker blinked, regarding Roth in silence.

“No one will speak of this!” Priest R

oth said. “To contaminate the township with such lies would be a crime worthy of the strongest censure.”

Jak had seen the priests' strongest censure before. The Silenced rarely came to town, but he'd seen them at the Horse-fair in Merrith. They cut the fingers from the ones who could write, but only the tongues from the peasants.

“Hender and Greyton will stay to guard the beast. The rest of us will return to town. We'll fetch chains for Hender to shackle it with. The trial will take place here so the evil will not spread. We'll stake it by the lake and burn it there once sentence is passed,” Roth said.

The priest set off immediately, as if the Maker's presence scorched him. He didn't look back, sure in his authority. The men fell in behind him. Jak's father pulling him along.

“If it tries to escape, Hender, kill it,” Roth said.

#

No-one spoke on the long climb to Cutter Pass. The path grew steep and the ground treacherous. Town-folk never spoke easy before a priest, but it seemed to Jak that each man carried a new burden of silence. He looked from one grim face to the next. Even Dain would not meet his gaze.

The Maker spoke true, I know it. Jak couldn't let the words out, yet they grew inside him, demanding release.

From the height of the pass Jak saw Hopetown in the distance. The shadow of the hills reached out across the plain for the cluster of tiny roofs. The men strung out behind Priest Roth now, as if unwilling to be drawn into his plans. They trudged one behind the other, ever more isolated, never looking back.

At the rear of the column Jak stopped walking.

The Maker spoke true, and I won't let them kill him!

A last glance at his father's back, and Jak turned to run. He ran until his lungs hurt, and then he ran some more. He crested the pass once more. Loose stones scattered beneath his heels as Jak rounded a corner above a precipitous fall. For the second time that day he began the descent toward the lake.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology