- Home

- Mark Lawrence

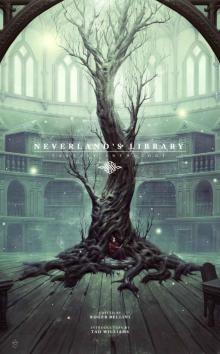

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Page 20

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Page 20

“Easy lad, you’re secret’s safe with me.”

“What?” he said, shocked by the man’s response.

“I saw what you did, I’m grateful to you. As far as I’m concerned, the reason Fanguard is still standing is thanks to you.”

“Thank you.”

“Did you do this to yourself?”

“No. My father did it when I was very little.”

“Genius,” Pignuis replied.

“You think?” he asked, staring at the crimson scale. For the first time he realized they represented something more than a man’s greed.

“Oh yes. Wish I had thought of it myself. Is your father…?”

“He’s fine. He’s resting. I want to help the others.”

“Then come,” Pignuis put his large arm around Ignis’s shoulders and pulled him close, “there is much to do before the ‘morrow and the threat still looms over us.”

Ignis allowed the man to lead the way, willing to do anything asked of him.

The Height of Our Fathers

Jeff Salyards

MY SISTER HAD LONG DARK LASHES that would often hook together to form a net in front of her eyes, and she would blink furiously to free them, eyes rolling white like a frightened horse. And this seemed to happen more frequently when she was excited, as she was when we stood before the tomb. I was looking around the mound, into the woods, trying to see if anything was coming upon us. This wasn’t the first time we’d broken into graves, but it would be our last. Together at least.

The Vorlu believe that each of us goes on a journey in the afterlife, that everyone should be outfitted according to our deeds and station. A babe is buried with a wooden toy in the hollow of a young tree, tarred in, so the two might grow strong and old together. A priest is laid in the earth with his bones and runes, staff and oils. A warrior, his war gear: spear, axe, shield, what have you. But a warlord—a leader of men, a pillager, a great man—he’s either burned in a pyre or buried in an underground vault in his helm and mail, armed with his finest sword, often accompanied by his horse, and his crypt is filled with fruit and meat, milk and mead, furs, coin, hunting horn, drinking horn, bow, glass, musical instruments, perhaps even a slave or two. Everything he would need in the afterlife to pass the time in comfort. A rich grave, indeed. And just the kind we stood in front of.

My sister, Soffjan, looked at me, eyes dark and alert, the cromlech of our ancestors leaning this way and that in the dying light, our breath beginning to show in the air. She looked at me, at the tomb, and then laughed. “Grandfather never did much like company.” I had misgivings, but I deferred to her that night, as I did regularly when we were growing up. She suggested our first robbery two summers before. It had always been graves from villages far off, but we couldn’t go much farther without our absence being noticed, and if someone from another tribe caught us at our business, the punishment would be death. If someone from our own tribe caught us, we figured we’d be publicly flogged or made to clean smegma for a year. And while scraping the prick of an unwilling stallion was deterrent enough for most, it wasn’t quite enough to put us off.

We stood in front of the mound, a pebble cairn as tall as a man with a layer of white quartz around the entrance shining bright as snow, and seeing nothing in the darkening woods, we moved the carved slab blocking the entrance. It wasn’t overly heavy—presumably fear of hobgoblins or spirits kept intruders at bay—and after looking at each other briefly, my sister and I entered the grave and waited for our eyes to adjust. The outlines of things would be enough—most of the tombs are constructed the same way, so we knew what to expect. We passed through the antechamber, crept into a corbelled passageway that led down to the burial chamber and all the goods contained therein.

There, we were completely blind. Most cats would have thought better and retreated at this point. I moved slowly, but I couldn’t help bumping into some jars and a bowl. Soffjan hissed, but it was hard to tell from where. And then I heard her stop moving and draw in breath. I asked what happened. She didn’t answer. I tried again. “What, what is it? Tell me!”

She said, “He’s here.”

“Of course he is. It’s his tomb.”

“No. I found him.”

I shuffled toward the sound of her voice, and bumped into her back. She was tall for a girl, even for a boy, and I hated her for it, sure I would never catch up. She reached out, fumbled for my wrist, and drew my hand forward. When it touched bone, I stopped breathing. We were both silent for a time, my grandfather’s knucklebones laid before us like misshapen die, and Soffjan asked, “What do you remember about him, Bray?”

I thought about it before answering. “He was big. Tall. A gray beard, but nothing on his top lip. Or the top of his head. He had a scar that ran the length of his jaw, breaking up his beard. He was mean. You?”

Even though she was older than me and surely remembered more, she said, “Nothing.”

“Do you remember how he died?”

“I think he choked on a chicken bone.”

That was her. Mocking the dead and living with equal vigor.

And with that we started looting. We shuffled about and began to catalog the items around the room, whispering what we found, sometimes examining them together, weighing the rot against the price we imagined they would fetch with the merchant. Wooden gameboards with painted pieces, a comb carved out of antler, both discarded. A harp, considered briefly, but the wood too warped. I found a spear with an engraved winged head—my people are prone to naming their favorite weapons, often believing them imbued with magic or power, and I traced the etched name of the spear, “Skybiter,” amid many runes. The ash staff was bent and felt like it might not withstand more than a thrust or two, but the head would barter well so I laid the spear on the ground in front of the table.

My sister did the same with a large round shield. The wooden planks were beginning to separate and warp, but the umbo had fared well enough. And so it went, this to steal, that to stay, the pile in front of the table growing, the rest of the chamber strewn with everything else. Having finished searching the goods around the dead, we began to go through the items on his person. We moved to the head of the table. Soffjan unbuckled the helmet and tried to pull it free without disturbing where his bones lay—we might have been graverobbers, but we had no intention of being desecrators if we could help it. But we couldn’t. His skull slid away from the other bones and fell free as she hoisted the helmet, clattering on the dusty floor.

The padded lining was soiled and rotten, no doubt the meeting hall of a legion of beetles and spiders, and the metal was tarnished and rusty, but the helm was ceremonial, with gold fittings and elaborate silver engravings, never having been worn in battle, and it was certainly worth keeping. I found a brass torc resting on his neck bones and slipped it into my tunic, ice cold against my skin. Soffjan undid the round clasp holding a beaver skin cloak, dropped it in a pouch at her hip. Beneath the cloak was a shirt of mail, so rusty it hurt to touch, the links all but forged together.

Then we found what we were really looking for. A buckskin belt across what remained of his hips, and a sword in a scabbard. We both jumped for it at the same time, nearly knocking the sword, ourselves, and the boneworks to the floor. We stopped wrestling. I felt for the buckle, undid it. My sister said, “This… this I remember.”

Our hands moved up the scabbard. Wood covered in leather, the inside lined with wool, no doubt yellow as piss now. Soffjan got to the hilt quicker and slid the blade free. She stepped away and I heard the sword rush through the air. “Stop. Let me see it, too,” I said. I didn’t hear any more swings but didn’t trust her. “And don’t stab me—I’m on your right, I think. Let me come to you.” I did and we held it together. It was a broadsword, both the pommel and the ends of the guard carved with the heads of boars. The fuller was wide and long, and the blade was beautifully balanced. Even in absolute darkness I could tell it was a wonderful sword. I hit my sister on the arm with the scabbard and han

ded it to her. “Put it back, Soff. We have more to claim yet.”

She slid it home, reluctantly, and laid the sword against the wall. We were examining his boots when Soffjan grabbed the sleeve of my tunic. “Did you hear that?”

I listened but there was only our heavy breathing. “What? What did you hear?”

She paused. “I don’t know. I thought—” And then we both heard it, a scrape, at the entrance from the sounds of it. It could’ve been a dog sniffing about, a mountain cat looking for moles, a large mountain cat looking for dogs. But it also could’ve been someone who didn’t share our disregard for tradition, sanctity, and ancestors.

Soffjan let go of me and moved away. “Wait. Where are you going? Wait,” I whispered, and I might have done too good a job because she didn’t respond. She picked something up and moved again, no doubt toward the entrance. “Wait!” But it was no good. It was rarely any good with her. She did as she chose. And she chose the sword.

Phantoms didn’t frighten me, but something scraping in the beginning of night is usually armed with blade or tooth. And both scared me quite a bit just then.

I felt my way through the pile in front of the table, grabbed the shaky spear, and hurried to catch up, nearly stabbing my sister in the stomach. Her eyes had adjusted more than mine and she dodged me, pushing me against the wall with her forearm. “Careful,” she said. “And be quiet. Listen.”

I did, but heard nothing but our breathing and the wind. I waited and began to make out the entrance ahead of us, the outline of my sister, the outline of myself. “I don’t hear anything. Do you? Do you hear—”

She snapped, “You. I hear you. Shut up.”

We waited together. Nothing. I volunteered, half-hoping, half-believing, “Maybe it was a squirrel. Or a deer. Maybe—”

“Shut. Up.”

I did. And we waited some more. Just as I was about to speak again we heard a few pebbles fall down the stairs. We moved toward the entrance together. Soff held the sword before her with both hands and I followed close behind, looking quickly to our left. Nothing there, and as I turned back to the right there was a blur of movement. A crouching figure sprang up, smashing my sister in the head with a shield and sending her sprawling to the grass.

I thrust the spear forward but the shield came whipping back down and almost wrenched the spear out of my hands. Thanks to my useless father, I wasn’t as familiar with spear fighting as I should’ve been at my age, but I knew you couldn’t possibly beat a swordsman with a shield if you stayed in his range, so I took a few steps back.

The swordsman was wearing a helm with a leather aventail covering everything of his face save his eyes. He was rangy and familiar, but I didn’t have time to think about it as he advanced. I thrust again, this time at his exposed left leg, but he parried it easily. I retreated, sending out thrusts, and he kept closing, almost lazily, swatting them aside.

My opponent moved like a veteran of a hundred battles while I wasn’t the veteran of one, and spears work best with other spears in a shield-wall, or from horseback. So, martial inequalities being what they were, I threw the spear at my opponent’s foot and ran the other way. Does that sound cowardly? It should. It was. But just then my sister wasn’t my concern. My skin was. So I sprinted as if my grandfather's wraith was behind me.

But I only took three steps before pain exploded across my shoulder and then the backs of my legs. I collapsed in the grass, rolled to my side, reached behind me to feel for blood when a boot caught me in the stomach. I closed my eyes, struggling to breathe. When I finally opened them again, my assailant was resting on one knee beside me, helm off, beard in braids, but his upper lip bare like his father before him. “Be glad it’s the flat of the blade, boy,” My uncle Sirk said. And with a flash of silver he smacked me again.

Once Soff had been roused, my uncle led us back like cattle. If we had an inclination to run, neither of us acted on it. There was nowhere we could go on the island that Sirk couldn’t follow, and if he had to capture us twice, the second would have been even less gentle.

Our grandfather’s tomb wasn’t far from the settlement. Still, it felt like an eternity before we finally left the woods and approached our village—it was small, situated in the foothills of a broad mountain. There were a dozen or so turf longhouses positioned around a large firepit. As was the case on most nights before the snows fell hard, a group of men and women were gathered around the fire, drinking, glassy-eyed, and listening to the skald recite epic poems they’d all heard a thousand times before.

Our uncle told us to stay where we were and walked over to our parents. He threw his helmet down and though we couldn’t hear him, we didn’t have to. Our parents both stood up and looked in our direction, shaking their heads. Sirk spat again and threw the sword point first into the dirt, where it stuck, quivering, reflecting firelight.

Sirk continued raging and our father looked at him the way a man looks at someone speaking a foreign tongue in a threatening tone, uncomprehending and afraid. When a Vorlu chieftain dies, his holdings are split equally between the children, in this instance, three sons. And as might be expected in such a backwards system, fratricide often results. Age doesn’t matter, only strength. And my father was a weak man who preferred his beehives to the battlefield. So his brothers fought it out, and my uncle Drunik drove Sirk and my father from his lands, to the fringe. Sirk had been skirmishing with Drunik on and off ever since, with mixed results. But my father, well… when he died my sister and I would split a handful of underfed goats, a meager flock of sheep, and far too many beehives.

Which, besides her innate perversion, was why Soff was so willing to crack open tombs and dig up the dead, and why I was so willing to follow her. War is the primary means of accumulating wealth in my homeland, graverobbing a distant second. Even if it was reserved for graves outside the tribe.

Our father was a short, jowly man who moved slowly, talked slowly, and always looked as if he drank too much despite not drinking at all, and he made his way around the fire with even less speed than usual, each step seemingly more weighty than the last. Our mother had no such hesitation. She all but sprinted, shouldering onlookers aside until she stood before us, the veins in her arms and throat full to bursting. She looked at my sister, looked at me, nostrils flaring, fists clenched, trying to determine who deserved the greater portion of bile.

And then she slapped me as hard as I’ve ever been slapped—and I’ve been slapped viciously on a number of occasions—and I bit my tongue and spit blood. The men in the circle laughed at this, slapped each other in the face too, and drank some more.

Our father reached us and stood there, cheeks billowing, eyes teary as if he’d just been the one slapped. Sirk was with him, and said, “Your children must answer for this. Now.”

My father looked at us, obviously wanting to ask if we’d done this thing, hoping we could assure him somehow we hadn’t. But he knew his brother wouldn’t lie about something as grave as graverobbing, and he looked ambushed, defeated, his thick lips moving slowly and soundlessly in the middle of his thin beard. If I hadn’t been so afraid, I might’ve felt sorry for him. Looking back, I wish I’d shown remorse, penitence, something. But I’m sure all he saw in my face was regret I’d been caught and terror of punishment. Soff gave him even less, stonefaced.

He turned his back on us, saying only, “Come,” and walked toward our longhouse.

My uncle let him go alone for a bit and then smacked me on the back where the blade had landed earlier, and I yelped, again to the amusement of the drunkards around us. My mother grabbed a handful of Soff’s hair, twisted it in her long fingers, and pushed her forward as well, but Soff was silent. I wish I could’ve been half as stoic, but the best I could muster was not crying or pissing down my leg.

Our father was waiting for us in the longhouse, having lit some rushlights, his back toward the door, arms at his sides as if he were holding heavy invisible stones. He heard us enter but didn’t turn around. Sirk pull

ed the deerskin flap shut behind us and our father took a deep breath, sighed, shoulders falling.

Finally, still not turning around, and in a voice so quiet it seemed he was talking to his weak shadow on the wall, my father said, “You didn’t know him well. Your grandfather. You were young when he died, and few knew him well. I’m unsure I did. You probably heard stories, though. He was a fierce fighter, a man feared and respected by enemies and allies alike. A bold warchief, embarking on raids others would have balked at. The few defeats he suffered he avenged quickly, viciously. For these and many other reasons, everyone was in awe of him.”

Our father turned around then, face flushed as if he’d been leaning too close to a fire. “You should ask your uncle about your grandfather’s exploits some time. Sirk fought for him far more than I did, that’s a fact. Your uncle knows a great deal about the glories of war. But there are other sides, too. Your grandfather was bold, brave, crafty, all true enough, but he was also cruel and unforgiving. He did things to his enemies that were… unspeakable.”

Sirk snorted. “Get on with it, brother.”

Our father kept his eyes on us. “War demands a strong stomach and a weak memory. But not all warleaders flay their prisoners alive, or gut them while the remaining prisoners watch. Not all warleaders carry a bag on their hips filled with the heads of their foes. Or burn eyes out with firebrands, or drive victims off cliffs, even while they beg for mercy.

“All this to his sworn enemies. But do you know when he was cruelest? Do you know when he was most vengeful? To those who lied to him, betrayed him. Stole from him. Just as you stole from him today.”

He reached up with both hands, put his palms on each of our cheeks. “I don't want to know who planned this. I don't want to know why you didn’t choose a different grave. All I want to know is…knowing what you do of the dead man you stole from, what do you think your thievery deserves, children?”

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology