- Home

- Mark Lawrence

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) Page 9

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) Read online

Page 9

Mia was halfway out of the car, freezing air gusting in past her. She stopped. ‘How are you doing this? Can you read my mind?’

Demus’s voice changed. It went soft. ‘I know because these are things you will tell me. I don’t know the number you were thinking of just then because you never told me that.’

Mia moved back into her seat, pulling the door closed; still angry, but with curiosity winning out. ‘What the fuck is going on?’

‘I’m a time traveller, Mia.’

‘Bollocks you are!’

‘Mia, I know about the mud scraper outside your house in Barking when you were two. I know you have a crush on Siouxsie from Siouxsie and the Banshees and have sworn never to tell anyone. Either I’m a mind reader, or you’re insane, or I came back from a time when you had told these things to someone. In fact, since we’ve just told them to young Nick here, you can assume I learned them from him.’

I sat silent, watching the exchange, wondering why Demus was hiding the fact that he was me. And how Mia couldn’t see it anyway.

‘But . . .’ Mia frowned, unable to squeeze her objections into words. She slumped back. ‘Tell me.’

Demus explained that when you come back through time you come back just as James Cameron predicted in Terminator. Buck naked.

‘That was a lucky guess, mind. He just wanted to show off Arnie’s muscles. The fact is, though, that it only works for living things. The equations that govern the universe don’t care about time. There’s no “now”, no past or present, just a solution to the equation. That’s how rocks see it. How atoms see it; planets, stars; antimatter, dark matter. None of it cares about “now”. Time is just a variable. We make now. Consciousness makes now. We live it and we can, with sufficient energy, move it about.

‘I took care choosing the place I came back to, as well as the time I came back to. I appeared outside the police station on Watkins Street at three in the morning of January the first. They assumed I was a drunken reveller and put me in a cell with some blankets. In the morning when they couldn’t get any sense out of me, they rustled up some old clothes. Really nasty old clothes, it has to be said. And pushed me out the door.’ Demus gave me a curious wink as if some kind of message were hidden among the detail. ‘I went straight to the Ladbrokes on White Ladies Road. I’ve memorised the results of quite a few races and the race meetings on New Year’s Day are always popular.’

‘But you had no money, right?’ Mia asked, hard-eyed and suspicious.

‘I didn’t. They wouldn’t even let me stay in the shop. To be fair I did smell pretty bad. But just before the first three races that came up I called out the winner through the door. After the third time, several punters came out and asked my opinion about the winner of the next race. I told them on the understanding that I wanted a quarter of their winnings. After that I had money, then quite a bit of money, and lots of friends who didn’t care how pungent I was.

‘Next I had to find somewhere to live on a cash only basis and set up my laboratory.’

‘Laboratory?’ Mia asked. ‘Figures that you’d be a mad scientist, I guess.’ She slapped the seat. ‘Shouldn’t this be a DeLorean?’

‘What?’ I asked.

‘A DeLorean, like the film.’

‘Oh.’ I knew she was talking about Back to the Future, but it only came out the month before, and I’d been kind of busy.

‘Were you building something to get you back to when you came from?’ I asked.

Demus shook his head. ‘I was building two of these.’ He reached over to the passenger seat and held up a circular device, a heavy-looking object like a metal headband sporting a collection of boxes and cylinders along its outer surface and connected to several cables. It looked rather homemade and significant amounts of duct tape had been used in its construction. ‘I had to simulate the manufacture using current day materials before I came. It wasn’t easy. But the technology I would have normally have used requires a massive infrastructure, and putting that in place would reshape the future. Which is exactly what I don’t want to do.’

Mia slapped the seat. ‘Wait!’ She shook her head. ‘I don’t care about your gizmos. The important question, if any of this is real, is why the hell some guy from the fucking future is here, now, stalking Nick, talking to me in a car?’

It was true. That was the important question and I still had no idea of the answer, even though it was me doing it.

Demus stared at her, as if choosing his words carefully. ‘I need to record your memories, Mia.’

Mia shot out of the car so fast I didn’t have a moment to object even if I’d wanted to. She left the door open wide and sprinted off down an alley between two low blocks of council houses.

‘Shit.’ Demus put his space-age headband back down on the seat. ‘Well, that went well . . .’

‘Seriously, you knew to be there to pick us up . . . but you didn’t see that coming?’ Clearly I was destined to become stupid as I grew older.

Demus sighed. ‘As well as recording memories, these devices can erase them. At some point in the near future you decide to erase your memories of recent events. My memories of them. By doing so you allow me to act however I choose without immediately jumping us off my timeline. I’m no longer forced to stick to the script. Things don’t have to go how I remember things went . . . because I don’t remember how they went. Events do, however, need to turn out the same as I remember them in the longer term.’

‘And why did I choose to blank my memory back to some point between Mia getting into the car and jumping out of it?’

‘You chose to do it that way because you remembered this conversation and realised that if you didn’t blank our memories in just the way I described then you would not be me, your recovery from leukaemia would not be guaranteed, and my plans would be ruined . . .’

‘If I buy that . . . and it’s a big if, why didn’t you remember that Mia needed money and just give her some? That would have avoided a lot of grief.’

‘I shouldn’t be able to remember any of this, if you recall. As soon as I showed up there should have been a whole new timeline. That’s the way it works. As soon as there isn’t a new timeline you start to drown in paradox, you set up an endless loop of second guessing yourself. Which is why it can’t happen. But it did happen. Somehow that loop got frozen in place and we’re stuck with what we got when the dial stopped spinning.’ Demus lifted his hands helplessly. ‘Over the next few days you are going to find yourself asking over and over “Why didn’t he just do this instead?”, “Why didn’t he just go back to this time instead?”, “It would have been so much easier if only . . .” And the answer to every single one of those questions is simply, yes, it would have been better, but that’s not how I remembered it happening and so I didn’t. Because if it doesn’t go down the way I remember it, then we’re on a new timeline, not mine anymore, and nothing I do here can make any difference to what happens in the future of my timeline after the point I left it to come back here.’ He dug in the glove compartment and pulled out a thick wad of ten-pound notes. ‘I knew she needed money. I can give her money now. I was going to do just that . . . but she’s run off.’

After Demus’s torrent of mind-bending nonsense, the money seemed like a cold, hard, actionable fact. Something I could use. ‘Give it to me. I’ll see if I can find her. She can’t have gone far.’ I reached for the offered cash and scooted along the back seat to leave by Mia’s door.

‘Bring her to the park on Sunday. Same bench!’ Demus called after me. ‘Tell her she’s the one who sent me!’

He shouted more, but I was off and running.

CHAPTER 11

I headed back toward the Miller blocks and caught up with Mia on the way. I guess home exerts a pretty strong pull in times of trouble, even if it’s the first place trouble will come looking for you.

‘Wait up!’

‘Go away!’ She sounded angry.

‘I’ve got money! Lots of it.’ I limped ahead of h

er, spreading the notes out in my hands.

She stopped at that, shaking her head. ‘This is crazy. Insane. That man . . . It can’t be happening.’

‘You sound like me when they told me I had cancer.’

‘People get cancer every day, Nick. This is different.’

‘I don’t get cancer every day. It’s different when it singles you out. Suddenly nothing makes sense. Just like with Demus.’

Mia sniffed and wiped at her nose. ‘I know that. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean . . .’

‘It’s OK. That’s my problem. Not yours.’ I held up a hand to deflect any objections and thrust the money at her with the other. ‘Take it. I got you into this hole. This should get you out?’

Mia reached to take the cash, then stopped, her hand halfway between us. ‘Taking credit got me into this mess. And they say to never borrow from or loan to friends.’

I smiled at ‘friends’. I wanted to be her friend, perhaps more than was good for me. She made me feel like I was part of something, part of the world, not just skating around the edges, too tied up in myself to join in. ‘It’s not a loan. It’s a gift. And it’s not from a friend. It’s from Demus, and I honestly don’t know what he is yet.’

And it was true. I didn’t really know who Demus was yet. I could be angry with last week’s Nick Hayes. Just how far a person could grow apart from themselves in quarter of a century, I didn’t know. Demus was wrapped around the same bones I was, and he had his memories of being me, filtered and edited by time and experience. But did that really make him me? Did we want the same things? Did we trust each other? Why on earth did he need to record Mia’s memories anyway? That made no sense. I should have asked, but I’d been too eager to go after Mia before I lost her.

Mia took the money, glanced both ways down the street, and started to count it. It took a while. ‘This could get me out from under Sacks. I’d have to take it to him. The other guy isn’t going to take . . . seven ninety, eight hundred, eight ten.’ She put one tenner in her pocket. ‘Eight hundred.’

‘No.’ I remembered the glitter of Rust’s eyes as he backed up the corridor, blood leaking between his fingers. ‘You have to go to the police over that one. He’s going to come after your mum.’

Mia shook her head. ‘Any sign of the coppers and Sacks’d tell Rust to do what he liked. You don’t grass. Not round here. Rust won’t touch Mum. He’d be mad to.’ She shoved the wad of money into her jacket pocket.

‘Your mum knows karate, then?’ I tried to imagine anything that would scare Rust off. Actually, a drunk with a broken bottle was scarier than karate, but I didn’t think it would do the job.

‘She knows how to look after herself.’ Mia snorted. ‘But that’s not it. You don’t know how come I can just go see a guy like Sacks.’

‘I don’t.’

‘He used to be tight with my older brother. They came up through the gang together.’

‘I didn’t know you even had a—’

‘Mike. He’s in The Scrubs now.’

‘Oh . . .’ I considered asking.

‘Wormwood Scrubs.’

‘Prison?’

‘Bingo.’ She put a finger to her nose and pointed at me with the other. Demus’s gesture. ‘Five years. Drugs.’ She shrugged. ‘Anyway, Sacks knows my mum from when him and Mike were little. Loyalty doesn’t run very deep with a guy like Sacks, but he likes to pretend it does, so he’s not going to let a psycho like Rust cut Mum up. It would make him look bad. And he wouldn’t have leaned on me so hard over the money. I mean, he would have held it over me, but he wouldn’t have pushed that hard. Only, that message seemed to have been lost on the new guy.’

I blinked. ‘So . . . is Sacks like, proper gangland, the firm, Kray twins and all that?’ The Krays were ancient history and I had no idea what had replaced them, but I assumed something had. ‘He’s big time?’

‘He wishes.’ Mia laughed. ‘He’s on the edge of that, hoping to get a place at the table one day, but right now he just runs an area and pays his dues. If he put a foot too far out of line, there are real heavies who would come and shoot it off.’

‘Unreal.’ Somehow, Mia being two steps from the hard core of London’s organised crime seemed every bit as difficult to take on board as Demus’s visit did. I guess maybe because Demus at least promised a mathematical proof!

‘Look, I’d better go,’ Mia said.

‘Uh . . . yeah.’

‘I mean, I need to get this sorted as soon as. My head’s a mess with all this craziness . . . and I have to see Sacks.’

‘I could come. If you want me to. You shouldn’t have to do this alone.’ No part of me really wanted to go with her. I didn’t want her to go either.

‘Better you don’t. Sacks doesn’t take kindly to new faces.’ She reached out to touch my arm. ‘Thanks, though, Nick.’

She hurried off and I stood watching. One of the streetlights flickered into life as she passed underneath, glowing an uneasy amber-red. I could still feel her hand on me.

‘Watch out for that guy,’ she shouted over her shoulder as she turned the corner. ‘He could be up to anything.’

I lifted my arm to wave and dropped it, feeling stupid. Slowly I turned for home, sick in my stomach and sore in every limb. I had chemo tomorrow. Another visit to the white world of stainless steel and starch, and the super-clean lie that everything would be alright. But I’d seen the future: one possible part of it had come back to see me. Know thyself. Philosophers have been urging us to do that since the ancient Greeks. I don’t think anyone really does, though. But I thought I probably knew myself well enough to know that everything was far from alright with Demus.

I knew a few of the kids on the ward now. Eva was the only one who really talked, though. They say it’s good to share, but in the end, whatever anyone says, we face the real shit alone. We die alone and on the way we shed our attachments. It started when I told the others I had leukaemia that day over D&D. Elton’s hug had stayed with me. It spoke volumes about his warmth and goodness. But perhaps Simon’s anger had been the most honest reaction there. He lacked the emotional wherewithal to translate it into something appropriate, but all of them were angry in their own way. I’d betrayed them. Broken the promise that I would always be there; that they could depend on me. Only Mia, who hardly knew me, was free of it. For her, it was part of her image of who I was now, not some ugly and unsettling addition. And, somehow, she hadn’t run for the hills.

‘What you thinking about?’

‘Uh.’ I looked up. Eva had come across, trailing her drip on a wheeled stand. She looked like shit, like she had been starved and beaten. Her hair had started to thin at last and her eyes had sunk into her skull.

‘You’re always thinking, Nick. Doing sums, thinking. Always inside. I’d get a headache.’ She sat at the end of my bed. We were halfway down the ward now on our one-way, kill-or-cure trip. Make that kill or pause.

‘I guess I am.’ All of us have a shell, a skin between us and the world that we have to break each time we speak to it. Sometimes I wished mine were thinner. ‘How are you doing, Eva?’

‘Oh, good,’ she said, and smiled a skull’s smile. ‘Apart from always being sick and everything. But the doctors say I’m doing well and I don’t need to have that operation anymore. And I’m really glad about that. I mean really, really glad.’

I let her talk. It made her happy. I wasn’t so sure it was a good thing she wasn’t getting her operation. It sounded rather like they thought she was too far gone. But I hoped it was a good thing. I sat there and took my poison like a man. Or a scared boy. And tried not to let Eva be alone, or to be alone myself.

At visiting time Mother was first through the doors, looking tired and worried. It shocked me to see so much on her face, the severe lines that time and care had left there. I wanted to talk to her. Real things, not just lies about how I felt and shared promises about holidays we would never take when I got better. I wanted to talk to her like one person to

another. But I couldn’t do it. I didn’t have the words. Maybe one day but not that day. And I realised that just as the disease was starting to take me away from the world, I was for the first time, in a short and self-absorbed kind of life, starting to really see it for what it was. The beauty and the silliness, and how one piece fitted with the next, and how we all dance around each other in a kind of terror, too petrified of stepping on each other’s toes to understand that we are at least for a brief time getting to dance and should be enjoying the hell out of it.

Elton and Mia arrived about ten minutes later and shook me out of my strange state of mind. Of course, with Mother there they couldn’t say too much, but Mia looked happier. She’d put on her war paint and cast herself in beautiful monochrome, all dark eyes and small smiles full of . . . something good.

We talked about nothing important. Somehow, I never questioned my assumption that this should stay between us and not be shared with Mother. I think I was protecting her from additional fear for her child, and less selflessly I was protecting my ownership of all this craziness that had dropped into my lap. I wanted to be the one making decisions about it . . . to the extent that decisions could be made.

Mia said something about putting her money in a sack, and I knew that the debt was settled. The details didn’t worry me. I was just happy she was there. Pathetically happy, truth be told. Elton saw it, even if Mother and Mia mercifully didn’t, and on their way out he shot me a grin that said so.

‘Is that your girlfriend?’ Eva dragged her stand over after her parents had left. She sounded in awe.

‘Nah.’ I leaned back on my pillows, unable to suppress a smile. ‘But she is pretty cool, though.’

CHAPTER 12

I didn’t make it to school again that week, but I made it to D&D at Simon’s house that weekend. I took a bowl with me to be sick in, in case I couldn’t reach the bathroom. Truth may often be the first casualty of war, but dignity is definitely the first casualty of disease. I was shiny headed beneath my black woollen hat now, and I looked as if I had stayed up all night for a week. I felt like crap, too. Demus must remember what it felt like to be this way; he’d lived through it and given me something to aim at. Still, I found it hard to forgive him for coming back from the future to make headbands that looked like props for a low budget sci-fi film, rather than to brew up some super cure; if not for the leukaemia, then at least for the nausea.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

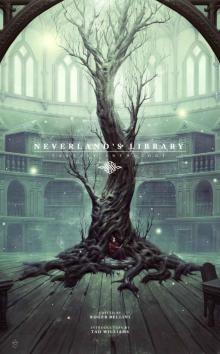

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology