- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Page 8

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Read online

Page 8

‘A clever young man like yourself will have figured out Mr Guilder’s plan for self-preservation by now.’ Rust fixed me with his singular stare. He often referred to my age as if we were a generation apart, though in truth he was only seven years older.

‘He told it to me himself. He wants to jump forward to a time when doctors are able to cure him.’ Rich people had been trying to beat the clock for ages. In California there were freezers full of the heads and bodies of those hoping to be defrosted in an age where they could be resurrected. I guess the ancient Egyptians had been trying much the same thing with their mummification and bottled vital organs. Freezing heads wasn’t much of a step up from removing the brain through the nose with a sharp hook and sticking your kidneys in an earthenware jar. I didn’t ask why Guilder was worried. What disturbed me was that he might have figured out why he should worry.

‘Mr Guilder has noted that you and the lovely Mia are the last in this queue,’ Rust said.

‘How observant of him.’

‘And that nowhere else on the planet or in our history has any other discovery similar to the one in this cave been made.’

I tried to hide my nervousness in a shrug. ‘There’s a kind of self-regulating loop at work. If there were historical records from the sixteenth century of a “witches’” cave full of time-trails, then nobody in the future would choose that cave to head back to the past in. They wouldn’t want the sort of reception they might get. So almost by definition, the places travellers use will be ones that stand the test of time.’

Rust eyed me in that predatory way of his that always made my throat constrict and my words dry up. I knew him to be capable of all the horrors I could imagine and quite a few more besides.

‘You’re lying.’

‘I’m not.’ I was, though, and the denial I managed to squeak out was not convincing. The truth was just what Demus had told me on our very first meeting. And I believed it not because I trusted him, but because I’d worked out the mathematics for myself. It is a lot easier to prevent time travel than to achieve it. The mathematics are simpler to work out. The idea is simpler to implement, requiring less advanced technology, and the energy requirement is much smaller. It just so happened that I was so far ahead of the competition, partly because of the head start that Demus had given me, that, based on the evidence before us in the cave, I was going to be able to invent and implement backward time travel before anyone else discovered the means to stop it. I, of course, knew how to stop all time travel right now. It just required a network of fairly simple temporal disruptors, each of which required an engine not much bigger than that of passenger train and would, for several thousand square miles around them, increase the energy requirement for time travel from the already ‘extreme’ to ‘unfeasible’. In short, it is a lot easier to close the door to time travel than to open it, and soon after Demus departed 2011 that door must have closed for good.

‘You know how I know you’re lying?’ Rust asked.

‘I’m not lying.’

Rust shrugged. ‘It’s good that you don’t know, or it would be harder for me to keep on spotting it.’ He stepped closer. Uncomfortably close. ‘You have a tell. Like a bad poker player. I know when you’re bluffing, Nick.’

‘I’m really—’

‘Mr Guilder is planning to take his trip into the future very soon. He’s tasked me with ensuring that the journey goes smoothly and as far into the next century as planned. Some of his other researchers have suggested the possibility that some kind of barrier could be erected, preventing travel in either direction.’

‘Other researchers?’ The idea that Guilder might have other academics studying the same thing should have occurred to me already, but somehow it hadn’t. The sin of pride, I suppose. But nothing in the open literature indicated anyone was considering a barrier, let alone close to discovering the theory behind it. ‘What others?’

‘Several prominent mathematicians and physicists in America. Others in Switzerland, France and Poland.’ Rust ran his strangely grey tongue over narrow yellow teeth, keeping his gaze on me. ‘The thing is, it seems strange to Mr Guilder that more than one of these very clever scientists has, on the basis of the early work of yours released to them in strict confidence, independently suggested that some kind of barrier could be constructed. Whereas not one of them has come anywhere near to a solid solution to travelling forward in time any faster than you and I are doing right now . . . And while you’ve already solved that problem, you’ve said yourself that going in the opposite direction is much more difficult.’

‘It is.’ Going forward in time presents no paradox issues. It’s the equivalent of having a long sleep. Einstein showed it was possible before the First World War. When you wake up in the distant future you’re a curio, an anachronism. Everyone else knows things you want to know. Going back, on the other hand, makes you a rock star. Suddenly you know things nobody else knows. You have all the secrets. You’re unique and powerful. If Demus hadn’t been constrained by his desire to save his Mia he could have used what he knew to become the richest, most famous, most influential person on the planet. ‘Much more difficult.’

‘And over there . . .’ Rust pointed to the top of Demus’s head, visible at the back of the ranks. ‘. . . is proof that you achieved your goal. You’re heading back somewhere . . . back past 1992, at least. Where do you think you might be heading, Nick?’

‘I don’t know. I guess I still have twenty years or so to make up my mind on that.’

‘But the real point here’ – he jabbed my chest with a sharp finger – ‘is that you made it. Your future self left next millennium and came back to this one, and after that the door seems to have closed. And that worries Mr Guilder. What if the door is closed both ways? What if medical science twenty years from now still can’t cure him? You see my problem here, Nick?’

A sudden terror gripped me. ‘He sent you here to kill me?’ Guilder didn’t really need me any more. For him, backward travel was an optional extra rather than the goal. I backed away towards the table covered with Creed’s gadgets. I didn’t want to die in this cave. I didn’t want to die anywhere, but somehow the idea of dying in the chilly depths of the earth, and having Rust be the one to do it, made it worse. ‘You can’t! It doesn’t happen like that!’

Rust took something from his pocket and calmly unfolded it. A knife, gleaming in the floodlights: a small, wickedly sharp blade, not the sort that offered a quick exit. ‘We carve our own future, don’t we, Nick? Isn’t that what you say? Every choice splits the world?’ He waved an arm at the naked travellers. ‘When I split you open, another me will decide to let you go, and all this will belong to that Nick instead. Isn’t that how it works?’

The back of my legs bumped against the table where Creed had been working and something delicate fell to the floor with an expensive crunch. Against all sense, instinct had me turning to save it. Despite already being too late and the move presenting my back to a psychopath with a knife, I was on my knees among the power lines reaching for the device before I knew what I was doing. A second later I saw my chance. I took a handful of cables, gave a sharp yank, and in an instant all the lights died.

Rust rushed forward with a shout of annoyance, but I was already rolling away, toppling the table in the process. I heard him trip over it with an oath.

‘This is stupid.’ Rust clattered about, presumably tangled in the table and powerlines. ‘Where are you going to run to?’

I wasn’t running anywhere. That would make noise that he might follow. I was crawling determinedly in a direction I hoped would take me to the far end of the cave. My main fear was that Rust would reconnect the lights and find me still crawling across the mud floor before I reached the tunnels.

‘You’ll get lost and die in these tunnels if you run off!’ Rust shouted.

I kept crawling. I’d decided I would rather starve in the dark than give Rust the satisfaction of slicing me up. I discovered the rear wall by bangi

ng my head against it. I managed not to cry out in pain, but just barely. Feeling my way along the rock, I soon located what I hoped was the tunnel I was looking for. I got to my feet and began to hurry as fast as I dared, arms raised defensively before me.

‘Guilder didn’t send me to kill you, you idiot!’ Rust’s shouts faded in the distance. ‘He needs you—’ Another turn of the passage swallowed his voice.

It’s a scary thing being alone in the dark: cold, wet and lost. But it’s a very different kind of fear to the one you experience when seeing a steel blade in the hands of a man who wants to cut you open with it. Yes, I had seen myself in the cave coming back through time, but that wasn’t a guarantee of survival; just an encouragement. I wasn’t indestructible. If I jumped off a building, I would die. It would mean that I had somehow split the timeline without Demus to help me and that the man in the cave wasn’t truly me. I couldn’t run blindfold into traffic. And I couldn’t let Rust stick me with that blade.

I moved on slowly now, feeling both walls of the tunnel for any side passages. All my senses strained to extract something of use from the blind dark. I’d run without a plan, driven by terror, but I wasn’t without hope. The map Creed had pulled out to show me where they had found Demus’s footprint had shown me rather more than that. It had shown me the way he went in order to get out at a time before Guilder installed his handy elevator. I’d only had a brief glance, but I have a good memory and now I was squeezing it hard to extract every twist and turn of the tunnel that I hoped I was in, and that would eventually emerge in a nearby forest.

I banged my head on the rock again, three times, and stubbed my toe, which hurt even more. Speed was important. Speed could get me killed, too; more likely by getting me lost than by braining me on a low ceiling, though both were possibilities. But speed could also save me. If I was too slow, I’d find Rust or one of his associates already waiting for me at the exit.

The thing about maps is that what looks like three inches on the page might be three hundred yards or three miles on the ground, or in this case underneath it. And when you can’t see where you’re going, three miles can seem like thirty. I pressed on with blind faith. After all, a timeline with my name on it was waiting back in the cave, and I was determined to be the Nick Hayes who set it off in 2011 and rode it back to 1986.

As hard as I tried to keep my mind on the business of not leaving the main tunnel and not dashing my brains out on rocks above, my thoughts still wandered. I needed a plan. If I ever reached the surface again, that would only be the start of my troubles.

I figured that, for once, time was on my side. Guilder was clearly running out of it and planning to make his move. If I just stayed unavailable for long enough – a few weeks, perhaps – then everything should sort itself out. Guilder would either shuffle off his mortal coil in the present, or sling himself into the distant future. And if he hit a barrier not long after my departure in 2011, well, he would just have to hope they had the cure for whatever ailed him by then. If I set the police on Rust for good measure, that should keep the man busy, and also dissuade him from killing me since he would be top of the suspect list. Rust was a curious creature: a bastard, yes, but one who lived by his own set of rules based on debt and obligation. It seemed likely that once Guilder was gone, Rust would have no reason to pursue me. I hoped so, anyway.

After several lifetimes spent stumbling through pitch-black tunnels, or perhaps half an hour, I found the way growing narrower, the floor underfoot more muddy. Soon I was splashing through icy ankle-deep water while the rocks grazed my elbows on both sides. The narrowing continued inexorably.

‘Shit. Shit. Shit.’

The water had reached mid-thigh and was heading towards the zone where men are wont to gasp and to start walking on tiptoes. Worse still, I had had to turn sideways to fit along the passage. One ear slid over wet stone while the rock on the other side was so close I could barely get my hand between it and the other ear.

There are various processes in life where you’re carried on past the point of no return despite yourself, and you find that the only option is to plunge on. An argument developing into a fistfight gathers its own momentum; ill-advised sex, too: with both of them you reach a point where pulling out ceases to be an option. The tunnel was threatening to become my third example. Could I back out now, wet and shivering, and try to find an alternative route, blindly feeling my way and having lost all faith in my flash reading of the map? Or did circumstance compel me to push on, even as the rocks threatened to trap me in a grip that would no longer allow any retreat? Would I wedge myself into some dark crack and leave a skeleton to moulder away as the centuries ticked by?

The tunnel was slightly wider lower down, so I started to crawl, my mouth just above the water, head scraping the rock above. The crack began to tighten even at this level, and it occurred to me that soon the mechanics of crawling through tight spaces would only allow me to inch forward, with reverse gear ceasing to be an option.

I’ll admit to panic, to tears, and even to appeals to any god who might be listening. But in the end, it was the memory of Rust’s knife and his evident pleasure at the thought of using it that drove me forward. That, and the faintest hint of motion in the air. I crawled and wriggled and splashed and during a shivering pause for breath I hoped that none of the travellers had been fat, because if they had it would have required a long diet before they escaped this way.

Reason suggested that the travellers would have practised this exit, and that it would be a bastard to get through; otherwise, the cave they travelled in would have been discovered in antiquity. So I squirmed and cursed and scraped myself across cold damp rock and wept, and finally left the icy water behind as I struggled into a wider space.

Something else was different here, but it took me an age to figure it out. The difference was that I could see! Kinda. I could see the faintest of shapes. Light – well, a handful of photons at least – was leaking in from somewhere. I advanced faster than was sensible and came to a sudden, painful halt against a sturdy metal grid.

‘Bastard thing!’ I backed off, rubbing my arms and forehead, before returning to inspect it: a rectangular grid of bars, each about half as thick as my little finger, the gaps between them large enough for four fingers to pass through, but not a hand.

‘Crap.’ Guilder had had the exit sealed off. After all that struggling, I was still trapped. I felt my way to where the bars joined the rock wall and tugged as hard as I could. I felt pretty sure that my fingers were bleeding, but the metalwork hadn’t budged even a fraction of an inch. Maybe if I had days to tug at it something might work free, but I doubted I had even half an hour. Without a crowbar I had no hope.

I sat back with a sob of frustration, head against the rock, muddy, dangerously cold, and deeply terrified.

It took several minutes and three deep breaths before it finally struck me that if I survived this and did manage to continue being Demus, then that was me back in the cave heading towards the 1980s. In which case I would have come this way years ago and would have remembered to leave a crowbar somewhere useful. I started to pat about the walls for a place where I might have concealed a handy pair of bolt cutters or something similar.

As the minutes went by in fruitless search, my desperation increased. It seemed more and more likely that I wouldn’t survive this. That I had somehow forked from the timeline where I was Demus and I was no longer making his memories for him . . .

‘But then how would Demus even be in there with the others?’

I went to the grill again and began a fingertip search of the whole perimeter. Somewhere near the bottom on the right I found broken stone and rough metal.

‘Thank God!’ Even atheist scientists are apt to praise the local deity at such moments. The bars had been worked free of the tunnel wall for several feet. It felt as if the grill had been bent up and then forced back so that the damage would be less conspicuous. Then I got it: the traveller or travellers who had departed

recently, since Guilder had found the cave! Demus would have arranged for a crowbar or something similar to be waiting for them and given them instructions on finding it before they left. He would have remembered how I found the area that they’d loosened and managed to pull it back, thereby escaping.

So I did just that. It was buggery hard. The bars absolutely did not want to bend, even a little bit, and when they did they presented a small gap between the rock wall and a fringe of stiff metal fingers all eager to impale me. I struggled under them, tearing my clothes and my skin, and stumbled on, convinced that I must be bleeding to death from all my wounds.

Sixty seconds later I staggered, muddy, torn and bloody, from a narrow mossy crack into what felt like blinding daylight. I pushed on through a large holly bush, discovering by dint of stepping on the spikes of a million dead leaves that I had managed to abandon one of my shoes in the tunnels.

The first thing I had to do, other than lose myself in a manner such that Rust or Guilder’s other men couldn’t find me, was to find a phone and warn Mia.

I hobble-hopped through the woodland, turning my head this way and that for signs of pursuit. I could hear an occasional car, indicating a road ahead, but instead left the trees via open fields and hurried through acres of ripening wheat to climb a gate into another large field. There aren’t many places in England where you can walk very far in a straight line without hitting a road, and this wasn’t one of them. I soon found a country lane that wouldn’t be top of the search list, and set off along it in my single shoe.

Hitchhiking is easiest when you are young, female and clean. I had only one of those things going for me, so it was a while before anyone took pity on me. And by a while, I mean that I’d walked most of the way to Bristol and the entire sole of my right foot felt like a single huge blister.

The large black vehicle that crunched up on to the gravel verge behind me looked disturbingly familiar. A Land Rover Discovery with tinted windows. The driver flashed the headlights and waited for me, anonymous behind dark glass.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

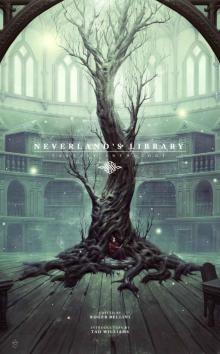

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology