- Home

- Mark Lawrence

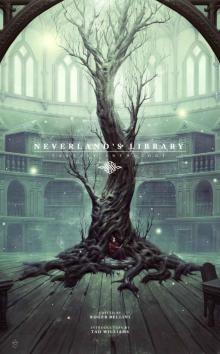

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Page 8

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Page 8

If the gators and the Wild Ones didn’t get to them first, that was.

Kord felt the first shivers in the cold stone that bespoke the impending arrival of Puell’s men. They became steadily stronger until his fingertips felt like they were being pricked by a thousand tiny pins and needles, and he fought the urge to snatch them away.

Then he felt the barest slackening in the vibrations, and knew the end of the column had passed. He reached out to the next man in line and then counted to thirty, one second ticking off for each man who passed the signal down.

And then he burst out of the brackish water with fifty-nine other men, the majority of their spears finding targets in the groins and thighs of Puell’s men.

But unlike his fellow mercenaries, once Kord’s first blow struck home, he didn’t draw his sword for a second. As his target cried out and grasped at the spear now piercing his leg just behind the knees, Kord slipped back into the water and swam for a thick stand of rushes he’d marked when Antrem’s men had first entered the cleared section and begun taking their positions. The long stems would hide him as he climbed from the water into the jungle overgrowth, masking his escape from anyone who might glance his way.

He took a route that would keep him well clear of the alligators he knew would already be heading toward the roiling, bloodied water and reached the rushes without incident. There, he pulled the plugs from his nostrils and took a great gulp of air. As he did so, he heard the shrill cry of a scarlet macaw and the answering whistle of arrows being loosed from a multitude of strings. He climbed up the bank on his hands and knees, fresh screams filling the air behind him. Only when he was well within the cover of the jungle itself did he risk a glance back, just in time to see a blue-faced man take an arrow through the eye. As the man fell into the water, nearly into the gaping maw of a waiting alligator, Kord realized it was Julion, the young mercenary he’d tried to protect from Bragga.

He felt a momentary pang of regret, then quickly pushed it aside. If he got what he wanted from Murdis, he could make it up to Julion’s family. If not, at least he could tell them that the young man had died quickly and honorably, which was more than most mercenaries’ wives ever got.

Unsure that the rationalization was enough to convince even him, Kord turned his back and disappeared into the jungle, the accusing sounds of death and horror slowly fading behind him.

#

The scriptorium appeared first as a kind of mirage: glimpses of stonework fairly shimmering behind a screen of trees. Brilliantly feathered birds took flight as Kord approached, their squawking and the flutter of wings the only counterpoint to the rustle of a warm breeze skittering through the leaves. This had always been a quiet place, Kord remembered. Murdis stressed contemplation, reflection, even reverence.

As a boy, that had seemed an unreasonable demand. Sometimes the tales Kord had read, of heroes and gods, had made him want to run, jump, fight, or simply cry out in youthful exuberance. Murdis chided him on those occasions, and more than once had taken away the book that had inspired such behavior, making him instead read something as dry as Moulten’s Mathematical Principles. Since most of the people Kord knew of, even then, were illiterate and could not count past ten without taking off their shoes, he had wondered how an entire book could be written about the topic. As it turned out, Moulten had filled his pages with the most mind-numbingly boring ideas Kord had ever encountered, before or since.

Now, however, after the never-quiet of the swamp and the brutal racket of killing, he thought silence would be a welcome change. To sit undisturbed for hours and read from one of Murdis’s texts—even if it was the Moulten instead of, for instance, his boyhood favorite, The Lives of The Warriors.

As he neared it, the landscape became more familiar. The trees were taller than they had been, and seemed to grow closer together. But the walkway wending between them had not changed, nor had the surprising way the scriptorium appeared after he passed the last bend. He knew it was close; he had seen it peeking through the trees. But there was still a startling moment when he saw a massive edifice of stone that looked like it would surely sink, sitting on a grassy hillock that rose from the soupy flats like a red welt on a maiden’s cheek, something that shouldn’t be there. The hillock almost seemed to defy the laws of nature, but as Murdis never tired of pointing out, there it was, so it had to be real.

The last time he had been here, Kord had been too young to appreciate the graceful intricacies of the scriptorium’s construction. His eyes picked out some as he neared it: the way it was built on a platform of stone that held it just above the high water mark on the hillock’s shore, the precise joining of stone to stone that kept out the rain, the arched doorway and windows that lent the walls strength to hold back the wind. He realized that Murdis had, in building this place, designed it not just as a place of learning but as a fortress. Reading, he’d said, strengthened the mind against whatever the world might hurl at it. Just as surely, this place stood as a bulwark, dedicated to preserving his intellectual ideals against the world’s unlettered hordes.

It was as quiet as ever. Even the birds had gone still. Kord stopped outside the doorway—open, as always—and raised his voice, albeit reluctantly. “Ho the scriptorium!” he called. “If Murdis be present, let him greet one he may have forgotten!”

He stood, waiting. The silence seemed suddenly oppressive, unnatural, and he felt the fine hairs on the back of his neck rise up. Was he being observed? As much as he wanted to look over his shoulder, he did not care to betray any weakness, so he kept his eyes locked on the dark doorway. After several moments he heard something from inside, a sound that revealed itself to be the shuffling of sandaled feet, and then a guard appeared, blinking away sleep.

“Did I disturb your nap?” Kord asked.

The guard held his spear diagonally, from his left knee to just above his right shoulder. Although Kord didn’t recognize him, he might have been old enough to have been serving when Kord had studied here. His neck was thick, his belly ample. Chances were his duties consisted of little more than eating and sleeping and checking the door from time to time. Murdis had never been overly concerned about security, and time had demonstrated the wisdom of that. Thieves went after treasure, and most didn’t know the value of ideas. Some even thought of Murdis as a kind of sorcerer, and superstitious terror kept those from his door.

“Never you mind,” the guard said. “State your business.”

“I already did.”

“Again, then!”

“Enough, Beril,” a familiar voice said from inside. The guard kept his spear at the ready, but his attention was split between Kord and someone approaching him from behind. A moment later, Murdis himself appeared in the doorway, and it appeared that Carna might have had the right of it.

Murdis’s coppery hair had gone mostly white, with threads of pale orange here and there. He was leaner than Kord recalled, his stubbled cheeks gaunt, his eyes hollow. A gown hung off bony shoulders; Kord thought that in a high wind, his limbs might clack together like a skeleton’s. But in those deep-set eyes a glimmer of intelligence remained, and more—recognition. A mouth with very few teeth in it opened in an unexpected grin.

“So you remember me, old man?”

“Forget that impertinent air? The careless disregard for cleanliness? The slovenly posture? Never, Kordell!”

Murdis started forward, his stride ungainly, his left leg dragging. He broke into a coughing fit, covering his mouth as his cheeks flushed, a ghostly shadow of the hale man Kord had known in his youth. When he was finished, he hawked and spat off the trail, then threw open his arms. “Come here, boy!” he said, his voice even more gravelly than it once was. “Let’s have a proper look at you.”

Kord stepped into his feeble embrace, and tried not to break any of Murdis’s ribs when he returned it. When it was over he stepped back.

“What of Kenaris?”

“Dead,” Murdis said. “Years, now.”

“Kenari

s gone, and you not well,” Kord said. “I’m sorry.”

“Nine hells!” Murdis replied. “I’m well enough for a dying man.”

“You don’t look so near death to me,” Kord lied.

“I thought that’s why you’d come.”

It had been, but Kord would be damned by the Lords of the Underworld before he’d admit to it.

“I was nearby, in the swamps, fighting battles that were not my own. I remembered you were close, and wanted to pay my respects.”

Murdis coughed again, and wiped his mouth on the back of his hand. Some spittle remained at the corners, white and foamy but flecked with red. “You never could lie for shit.”

“Truth!” Kord said. “I was reminded of you, so here I am.”

“Reminded by what? A bad case of the runs?”

“You sell yourself short, old man.”

“Last time I saw you, Kordell, you compared me to a weeping sore. Don’t think I’ve forgotten.”

“I was young, foolish, and rude.” Kord left it at that. Murdis had taken something from him, something it hurt to give up. He had been furious and in pain, and he wasn’t entirely sure that he had forgiven the old man yet. Or that he ever would. “I’d had enough of reading about adventures and wanted to live some. What did I know?”

“Did? You’ve learned something since?”

“Not everything worth learning comes from books.”

“Prove it.” Murdis started to laugh, but his laughter turned into a wet, racking cough that doubled him over. He beckoned with a gnarled hand. “Inside,” he managed, between coughs. “Come, boy.”

I’m no boy, Kord almost said. Not anymore. But as he followed the old man into the cool of the scriptorium, he knew that by comparison to Murdis, he always would be.

Inside, memory lay thicker.

The place might have been a frieze, cast from Kord’s recollection. Stone walls were lined with thick plank shelves, shelves stacked two deep with books. Scrolls were stacked on other shelves like logs beside a fireplace. The same chairs were scattered throughout, worn and threadbare now but holding together, as Murdis seemed to be, through willpower and stubborn resistance to change. Tables were thick with candle wax in places, worn smooth in others by arms sliding across their edges as books were painstakingly copied. A few people filled the big chairs, reading books. One ancient sat hunched over a table, copying the text from one volume into another.

“By the Thirteen,” Kord said. “Has nothing changed here in the years I’ve been gone? I think he was working on that volume even then.”

Murdis had brought his cough under control. He looked at Kord with glistening eyes, and clapped his palms together thrice. “Oh, some things have,” he said. “Some have changed quite a bit.”

The echo of his claps had scarcely died when she entered the room. Kord wondered if his eyes were playing tricks. He had seen plenty of women here—Murdis had always liked women—but none had looked like this one. She was young, older than Kord had been when he left, but younger than he was now, by several years. And she was beautiful.

“Your daughter?” Kord asked, though he doubted that could be possible. Murdis had never claimed any children that Kord had heard about, and it had only been fifteen—no, seventeen—years since he had left the scriptorium behind. “A niece?”

“Elinore, my companion,” Murdis said. “Meet Kordell. One of my less successful efforts, which I attribute more to his dull nature than to my inability to teach. But a reasonably pleasant lad, just the same.”

“I’m sure.” Elinore took a half step in Kord’s direction, as was traditional, then stopped and extended her left hand. Kord closed the gap, went to one knee, grasped the proffered hand and brought it briefly to his lips.

“Elinore,” he said as he released it. “Lovely.”

And she was. She was dressed like Murdis, in the fashion he preferred at the scriptorium: a loose gown of some flimsy material, with nothing on beneath it. Murdis hated false modesty, but allowed that absolute nudity might distract from the place’s mission; therefore, he settled on simple garb that left little to the imagination but at least covered the basics. The form this gown both revealed and hid was lush, as feminine as could be, but also strong. Her bare arms were muscular, her neck taut. Kord could tell from her hands and feet that she’d led an active life, a physical one. She was no pampered scholar, that he knew.

Her face, too, was both lovely and contradictory. Intelligence was evident in the slant of her brown eyes, in the set of her mouth and her firm jaw. Her features were as finely crafted as one of Murdis’s most prized books, and her auburn hair was loose, framing her face, hanging past her shoulders. She was not dolled up like one of Antrem’s favored whores, but wholly natural and prettier for it. Yet, in the slight upward tilt of her head and what was probably an unconscious compression of her full lips when she smiled at him, he read ambition, and perhaps a tinge of resentment, as if she knew why he had come, and disapproved.

“Call me Kord,” he said. “I’m honored to meet you.”

“Call me Elin,” she replied. “He talks about you all the time, Kord.”

“Liar,” Murdis said.

“Ignore him, Kord.”

“I always have.”

“Smart man.”

“Not to hear him tell it.”

“I’m certain,” Elin said, “that you’ll have plenty to tell me about our mutual friend Murdis. I trust you’ll share?”

Kord ignored Murdis’s glare, tempered as it was by a grin he half-heartedly tried to conceal; the old man was clearly glad his former charge and his new friend were getting along. “Lady,” Kord said. “Once I start, you won’t be able to stop me.”

#

Elin waited until Murdis’s breathing was as even as it ever got these days before slipping carefully from their shared bed. He’d been a virile man when she first met him, though many would have considered him well past his prime, even then. But the lung sickness he now fought took all his energy, and though she still lay with him, it was for comfort only. His days as generous lover were over; how much longer he would remain as generous patron remained to be seen.

As she stood over him, gazing down at the unsteady rise and fall of his chest, she thought about how easy it would be to end it for him. A pillow, applying the strength of arms more used to swordwork than scribing, perhaps a brief, ineffectual scrabbling as he fought. But perhaps he wouldn’t fight, at that. He had to know he’d be greeting the Sixth Lord sooner rather than later. If he’d just been willing to leave the scriptorium, with its heat and humidity that hung in the air like the scent of decay, and gone somewhere cool and dry, the illness might not have progressed to the point it was now—the point of no return, no healing, no end other than a slow, painful loss of strength, and vitality, and hope.

But Murdis was as stubborn as he was wealthy, and so they stayed, and she watched him waste away, and her opportunity to find the Hand of Uxlabal along with him.

And now Kordell had shown up, complicating matters. Though the old man spoke of him roughly, it was the harshness of hurt that colored his words, not that of hatred. Murdis had wanted Kord to stay on at the scriptorium—maybe even run it after he himself had gone—but his foundling had had other goals in life. Goals that did not include fighting a never-ending and unwinnable battle trying to save old books and manuscripts from the ravages of time and the jungle, and from the arguably more deadly disregard and forgetfulness of men.

That Kord had returned now, when Murdis was so ill and she was so close to finding what she’d spent years looking for was no coincidence, of that she was sure.

The man was a study in contradictions. He was older than her by several years, though you’d never know it by the way he moved—trim and fit, he carried himself with the confidence of a trained swordsman who didn’t need to swagger to prove it. Dark hair and heavy stubble showing the occasional glint of silver gave some clue to his true age, as did the creases around his deep-se

t blue eyes, but were it not for the fact that she knew when he’d left the scriptorium and how old he’d been at the time, she would have pegged him as being much younger.

It was his eyes, she decided. There was nothing of defeat in them, despite what could not have been an easy life once he’d left these walls. Instead, they shone with spirit, and humor, and intelligence. And given what Elin had already learned about his upbringing here, she knew that intelligence was formidable, perhaps even more so than his well-muscled right arm and the blade it wielded.

There would be no middle ground with this man—he’d either be a valuable ally or a dangerous opponent when the time came. That Elin hoped he’d opt for the former was not simple mercenary efficiency on her part, though in truth, such considerations were never far from her thoughts—she couldn’t afford for them to be. But Kord’s lips on her hand had stirred something unexpected in her, something neither Murdis nor any of the multitude of men before ever had, and she was intrigued by it, and him.

But not so much that she’d let him stand in the way of acquiring the Hand. She’d come too far and worked too long and hard to allow that to happen, fascination or no.

If she could get him to help her, so much the better. If she couldn’t, then she’d get rid of him, by whatever means necessary. What she worked toward was more important than any one person, after all. Or any two.

She let herself out of the room, closing the heavy wooden door as quietly as she could behind her—no easy task, given the way it had swelled from years of exposure to moist air and so no longer fit well in its frame. The hallway she walked down was lined with more of the ubiquitous shelves, stuffed to overflowing with yet more books and scrolls and even clay tablets reminiscent of the homeland, inscribed with ciphers whose meanings Elin, for all her own education, could only guess at. In between some of the shelves hung tapestries, heavy curtains of fabric better suited for a northern keep than a jungle fortress. The scenes they depicted were equally out of place—thick-furred bears the likes of which she’d only seen in Murdis’s books, speckled wolves, snowy landscapes. Where the old man had acquired them was a mystery—why, a greater one still.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology