- Home

- Mark Lawrence

King of Thorns be-2 Page 8

King of Thorns be-2 Read online

Page 8

Vomit took me by surprise, hot, sour, spurting from my mouth. I crawled in it, gagging and gasping. Almost not hearing Father’s: “One more.”

With his third leg smashed, Justice couldn’t stand. He flopped, broken in the cart, stinking in his own mess. Strangely he didn’t snarl or whine now. Instead as I lay wracked with sobs, heaving in the air in gulps, he nuzzled me as he used to nuzzle William when he cried with a grazed knee or thwarted ambition. That’s how stupid dogs are, my brothers. And that’s how stupid I was at six, letting weakness take hold of me, giving the world a lever with which to bend whatever iron lies in my soul.

“One more,” Father said. “He has a leg left to stand on, does he not, Sir Reilly?”

And for once Sir Reilly would not answer his king.

“One more, Jorg.”

I looked at Justice, broken and licking the tears and snot from my hand. “No.”

And with that Father took the torch and tossed it into the cart.

I rolled back from the sudden bloom of flame. Whatever my heart told me to do, my body remembered the lesson of the poker and would not let me stay. The howling from the cart made all that had gone before seem as nothing. I call it howling but it was screaming. Man, dog, horse. With enough hurt we all sound the same.

In that moment, rolling clear, even though I was six and my hands were unclever, I took the hammer that had seemed so heavy and threw it without effort, hard and straight. If my father had moved but a little more slowly I might be king of two lands now. Instead it touched his crown just enough to turn it a quarter circle, then hit the wall behind his chair and fell to the ground, leaving a shallow scar on the Builder-stone.

Father was right of course. There were lessons to be learned that night. The dog was a weakness and the Hundred War cannot be won by a man with such weaknesses. Nor can it be won by a man who yields to the lesser evil. Give an inch, give any single man any single inch and the next thing you hear will be, “One more, Jorg, one more.” And in the end what you love will burn. Father’s lesson was a true one, but knowing that can’t make me forgive the means by which he taught it.

For a time there on the road I followed Father’s teaching: strength in all things, no quarter. On the road I had known with the utter conviction of a child that the Empire throne would be mine only if I kept true to the hard lessons of Justice and the thorns. Weakness is a contagion, one breath of it can corrupt a man whole and entire. Now though, even with all the evil in me, I don’t know if I could teach such lessons to a son of mine.

William never needed such teaching. He had iron in him from the start, always the more clever, the more sure, the fiercest of us, despite my two extra years. He said I should have thrown the hammer as soon as I lifted it, and should not have missed. I would be king then, and we would still have our dog.

Two days later I stole away from both nurse and guard and found my way to the rubbish pits behind the table-knights’ stable. A north wind carried the last of winter, laced with rain that was almost ice. I found my dog’s remains, a reeking mess, black, dripping, limp but heavy. I had to drag him, but I had told William I would bury him, not leave him to rot on the pile. I dragged him two miles in the freezing rain, along the Roma Road, empty save for a merchant with his wagon lashed closed and his head down. I took Justice to the girl with the dog, and I buried him there beside her, in the mud, my hands numb and the rest of me wishing I were numb.

“Hello, Jorg,” Katherine said. And then nothing.

Nothing? If I could remember all that. If I could remember that dark path to the cemetery of Perechaise, and live with it these many years…what in hell lay in that box, and how could I ever want it back?

Many men do not look their part. Wisdom may wait behind a foolish smile, bravery can gaze from eyes that cry fright. Brother Rike however is that rarest of creatures, a man whose face tells the whole story. Blunt features beneath a heavy brow, the ugly puckering of old scar tissue, small black eyes that watch the world with impersonal malice, dark hair, short and thick with dirt, bristling across the thickest of skulls. And had God given him a smaller frame in place of a giant’s packed with unreasonable helpings of muscle, weakness in place of an ox team’s stamina, still Rike would be the meanest dwarf in Christendom.

11

Wedding day

Mountains are a great leveller. They don’t care who you are or how many.

Some have it that the Builders made the Matteracks, drinking the red blood of the earth to steal its power, and that the peaks were thrown up when the rocks themselves revolted and shrugged the Builders off. Gomst tells it that the Lord God set the mountains here, ripples in the wet clay as he formed the world with both hands. Whoever it was that did the work, they have my thanks. It’s the Matteracks that put the “high” into the Renar Highlands. They march on east to west, wrinkling the map through other kingdoms, but it’s in the Highlands that they do their best work. Here it’s the Matteracks that say where you can and can’t go.

It’s been said once or twice that I have a stubborn streak. In any case I have never subscribed to the idea that a king can be told where he can’t go in his own kingdom. And so in the years since arriving as a callow youth, in between learning the sword song, mastering the art of shaving, and dispensing justice with a sharp edge, I took to mountain climbing.

Climbing, it turned out, was as new to the people of the Highlands as it was to me. They knew all about getting up to places they needed to be. High pastures for the wool-goats, the summer passes for trade, the Eiger cliff for hunting opals. But about getting to places they didn’t need to go…well who has time for that when their belly grumbles or there’s money to be made?

“What in hell are you doing, Jorg?” Coddin asked me once when I came back bloody, with my wrist grinding bone at every move.

“You should come out with me,” I told him, just to see him wince. I climb alone. In truth there’s never room for two on a mountaintop.

“I’ll rephrase,” said Coddin. I could see the grey starting in his hair. Threads of it at his temples. “Why are you doing it?”

I pursed my lips at that, then grinned at the answer. “The mountains told me I couldn’t.”

“You’re familiar with King Canute?” he asked. “It’s not a path I advise for you-since you pay me for advising these days.”

“Heh.” I wondered if Katherine would climb mountains. I thought she would, given half a chance. “I’ve seen the sea, Coddin. The sea can eat mountains whole. I might have the occasional difference of opinion with the odd mountain or two, but if you catch me challenging the ocean you have my permission to drop an ox on me.”

I told Coddin that stubbornness led me to climb, and perhaps it did, but there’s more to it. Mountains have no memory, no judgments to offer. There’s a purity in the struggle to reach a peak. You leave your world behind and take only what you need. For a creature like me there is nothing closer to redemption.

“Attack,” Miana had said, and surely a man shouldn’t refuse his wife on their wedding day. Of course it helped that I had planned to attack all along. I led the way myself, for the sally ports and the tunnels that lead to them are known to few. Or rather many know of them but, like an honest priest, few would be able to show you one.

We walked four abreast, the tallest men hunched to save scraping their heads on rough-hewn stone. Every tenth man held a pitch torch and at the back of our column they almost choked on the smoke. My own torch showed little more than the ten yards of tunnel ahead, twisting to take advantage of natural voids and fissures. The tramp tramp of many feet, at first hypnotic, faded to background noise, unnoticed until without warning it stopped. I turned and flames showed nothing but my swinging shadow. Not a man of my command, not a whisper of them.

“What is it that you think you’re doing here, Jorg?” The dream-witch’s words flowed around me, a river of soft cadence, carrying only hints of his Saracen heritage. “I watch you from one moment to the next. Your plans ar

e known before you so much as unfold them.”

“Then you’ll know what it is I think I’m doing here, Sageous.” I cast about for a sign of him.

“You know we joke about you, Jorg?” Sageous asked. “The pawn who thinks he’s playing his own game. Even Ferrakind laughs about it behind the fire, and Kelem, still preserved in his salt mines. Lady Blue has you on her sapphire board, Skilfar sees your future patterned on the ice, at the Mathema they factor you into their equations, a small term approximated to nothing. In the shadows behind thrones you count for little, Jorg, they laugh at how you serve me and know it not. The Silent Sister only smiles when your name is spoken.”

“I’m pleased to be of some service then.” To my left the shadows on the wall moved with reluctance, slow to respond to the swing of my torch. I stepped forward and thrust the flames into the darkest spot, scraping embers over the stone.

“This is your last day, Jorg.” Sageous hissed as flame ate shadow and darkness peeled from stone like layers of skin. It pleased me no end to hear his pain. “I’ll watch you die.” And he was gone.

Makin nearly walked into me from behind. “Problem?”

I shook off the daydream’s tatters and picked up my pace. “No problems.” Sageous liked to pull the strings so gently that a man would never suspect himself steered. To make Sageous angry, to make him hate, only eroded the subtle powers he used. My first victory of the day. And if he felt the need to taunt me then I must have worried him somehow. He must have thought I had some kind of chance-which made him a hell of a lot more optimistic than I was.

“No problems. In fact the morning is just starting to look up!”

Another fifty yards and a stair took us onto the slopes via a crawl space beneath a vast rock known as Old Bill.

When you leave the Haunt you are immediately among mountains. They dwarf you in a way that high walls and tall towers cannot. In the midst of the heave and thrust of the Matteracks, all of us, the Haunt itself, even the Prince of Arrow’s twenty thousands, were as nothing. Ants fighting on the carcass of an elephant.

Out on those slopes in the coldness of the wind, with the mountains high and silent on all sides, it felt good to be alive, and if it had to be, it was a good day to die.

“Have Marten take his troops and hold the Runyard for me,” I said.

“The Runyard?” Makin said, wrapping his cloak tight against the wind. “You want our best captain to secure a dead end valley?”

“We need those men, Jorg,” Coddin said, straightening from his crawl. “We can’t spare ten soldiers, let alone a hundred of our best.” Even as he argued he beckoned a man to carry my orders.

“You don’t think he can hold it?” I asked.

And that set Makin running in a new direction. “Hold it? He’d hold the gates of heaven for you, that man; or hell. Lord knows why.”

I shrugged. Marten would hold because I’d given him what he called salvation. A second chance to stand, to protect his family. For four years he had studied nothing but war, from arrow to army, the four years since he came to the castle with Sara at his side. In the end he would hold because years ago in the ruins of his farm I had given his little girl a wind-up clown and Makin’s clove-spice. A Builder toy to make her smile and the clove-spice to take her pain, and her life. The drug stole her away rather than the waste, and she died smiling at sweet dreams instead of choking on her own blood.

“Why the Runyard?” Coddin wanted to know. Coddin couldn’t be put off the scent so easily.

“The Prince of Arrow doesn’t have assassins in my castle, Coddin, but he has spies. I tell you what you need to know, what will make a difference to your actions. The rest, the long shots, the hunches, it’s safe to keep locked away.” I tapped the side of my head. For a moment though the copper box burned against my hip and its thorn pattern filled my vision.

“I’d be happier on a horse,” Makin said.

“I’d be happier on a giant mountain goat,” I said. “One that shat diamonds. Until we find some, we’re walking.”

Three hundred men walked behind us. Armies are wont to march, but marching in the Highlands is a short trip to a broken ankle. Three hundred men of the Watch in mountain grey. Exiting the sally port amid the boulder field west of the Haunt where the tunnel rose through the bedrock. No crimson tabards here, or gold braiding, no rampant lions or displayed dragons or crowned feckin’ frogs, just tatter-robes in rock shades. I hadn’t come out for a uniform competition. I came out to win.

Behind us rockets took flight, lacing the dull morning with trails of sparks, and leaving a loose pall of sulphurous smoke above the castle. Wedding celebrations to amuse the Highlanders, but also a convenient draw for the eyes to the north of us, the uninvited guests.

The Prince’s army had started to move, units massed in their attack formations, Normardy pike-men to the fore, rank upon rank of archers on the far side, men of Belpan with their longbows near tall as them, crossbow units out of Ken, beards braided, brown pennants fluttering above the drummers, each man with a shield boy hurrying before him. The archers stood ready to peel off and find their places on the ridges to our east, the useless Orlanth cavalry at the rear. Their day would come later, after wintering in the ruins of my home, after the high passes cleared and the Prince moved on to increase his tally of fallen kingdoms. The Thurtans next no doubt. And on to Germania and the dozen Teuton realms.

We came down the slopes west of the Haunt in a grey wave, swords, daggers, shortbows. I’d spent most of dear uncle’s gold on those bows. The men of the Forest Watch knew the shortbow, and the Highland recruits learned it fast enough. Three hundred recurved composite shortbows, Scythian made. Ten gold apiece. I could have sat every man on a half-decent nag for that.

The Prince’s scouts saw us. That had never been in doubt. A sharp-eyed observer on their front lines might have seen us across the mile or so that remained. But why would they be looking? They had scouts.

I picked up the pace. There’s nothing like mountains for making you fit to run. At first when you come to the mountains everything is hard. Even the air feels too thin to breathe. Years pass and your muscles become iron. Especially if you climb.

We moved quickly. Speed on the slopes is an art. The Prince of Arrow wasn’t stupid. The commanders he had picked had chosen officers who had selected scouts who knew mountains. They moved fast, but the few men that fell didn’t get up again before we caught them.

It’s always nice to surprise someone. The Prince of Arrow hadn’t expected me to charge his tens of thousands with my three hundred. That’s probably why we were able to arrive only seconds behind the first word of our advance, and long before that word could be acted on.

Three hundred is a magic number. King Leonidas held back a Persian ocean at the Hot Gates with just three hundred. I would have liked to meet the Spartans. That story has outlived empires by the score. King Leonidas held back an ocean, and Canute did not.

I could feel the burn in my legs, the cool breath hauled in and the hot breath out. Sweat inside my armour, a river of it under the breastplate. Hard leathers these, cured and boiled in oil, padded linen underneath, no plate or chain today. Today we needed to move.

When I gave the shout, we stopped on the rock field, scattered on the slope, two hundred yards from their lines, no more, close enough to smell them. On this flank, far from the archers bound for the ridge, men of Arrow formed the largest contingent, units of spearmen in light ringmail, swordsmen in heavier chain, among them the landed knights who had levied the soldiers from farm and village or emptied their castle guard in service of their prince. And all of them, at least the ones we could see before the roll of the mountains hid the vast expanse of their advance, marched without haste, confident, some joking, watching the sparks and smoke above the Haunt. The great siege engines creaked amongst them, drawn by many mules.

I didn’t need to tell the Watch. They started to loose their shafts immediately. The first screams carried the message of

our attack far more effectively than scouts still hunting for their breath.

Aiming at the thickest knots of men made it hard not to find flesh.

We managed a second volley before the first of the enemy started to charge. The Prince’s archers, massed on the far side of the army column a quarter mile off and more, could make no reply. Know thyself, Pythagoras said. But he was a man of numbers and you can’t count on those. Sun Tzu tells us: Know thy enemies. I had lost men I could ill afford patrolling these slopes, but I knew my enemy and I knew the disposition of his forces.

The Prince’s archers would have found us hard targets in any case, loose amongst the rocks and the long morning shadows.

Another volley and another. Hundreds killed or wounded with each flight. Wounded is good. Sometimes wounded is better than dead. The wounded cause trouble. If you let them.

The foot-soldiers came at us in ones and twos, then handfuls, and behind that a flood, like a wave breaking and racing across sand.

“Pick your targets,” I shouted.

Another volley. A single man amongst the forerunners fell, skewered through his thigh.

“Dammit! Pick your targets.”

Another volley and none of the runners fell. The dying happened back in the masses still milling in confusion, caught in the press of bodies. One of mine for every twenty of theirs. Stiff odds. If we’d managed ten volleys before they reached us we might have slain three thousand men. We managed six.

12

Wedding day

“Be ready to run,” I shouted.

“That’s your plan, Jorg?” Makin’s face could take surprise to a whole new level. Something in the eyebrows did it.

“Be ready,” I repeated. In truth if I had a plan I held no more than a thread of it, teasing it out inch by inch. And the thread I held told me, Be ready to run. Sun Tzu instructs: If in all respects your foe exceeds you, be ready to elude him.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

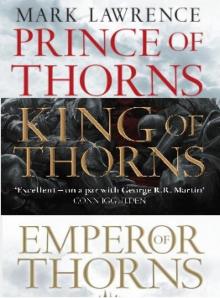

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

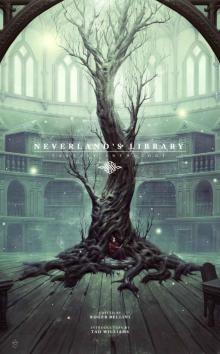

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology