- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Prince of Fools Page 6

Prince of Fools Read online

Page 6

“Oh, Jalan!” Alain drew the a out, making it a singsong taunt, “Jaaaalaan.” He really hadn’t taken having that vase broken over his head very well.

I jammed myself farther through the broken shutter, wedging both shoulders into the gap and splintering more slats. Some kind of webbing stretched across my face. Because right now I needed a big spider on my head? Once more the gods of fate were crapping on me from a height. I looked to the left. Black symbols covered the wall, each like some horrifying and twisted insect caught in its death throes. To the right, more of them, reaching up from where the blind-eye woman had returned to her work. They seemed to have grown along the sides of the building, like vines . . . or crawled up. There was no way she could reach so high. She planted her hideous seeds as she circled the building, painting a noose of symbols, and from each one more grew, and more, rising until the noose became a net.

“Hey!” Alain, his gloating turning to irritation at being ignored.

“We’ve got to get out of here.” I pulled free and glanced back at the three of them in the doorway, the old man clutching his wine looking on, bemused. “There’s no time—”

“Get him down from there.” Alain shook his head in disgust.

The drop to the street had been knocked off the top of the list of today’s most terrifying things, where it had nestled just above Alain and friends. The writing on the wall immediately outside swept all that other stuff right off the list and into the privies. I stuck both arms through the hole I’d made and launched myself out. I made it a couple of feet and came to a splintering halt with my chest wedged into the shutter frame. Something dark and very cold stretched across my face again, feeling for all the world like a web spun by the world’s toughest spider. The strands of it closed my left eye for me and resisted any further advance.

“Quick!”

“Grab him!”

Pounding feet as Alain led the charge. When it comes to wriggling out of things I’m pretty good, but my current situation offered little purchase. I seized the windowsill with both hands and tried to propel myself forwards, managing an advance of a few inches, jacket ripping. The black stuff over my face pulled even harder, pressing my head back and threatening to throw me back into the room if I lessened my grip even a little.

Now, nature may have gifted me a pretty decent physique but I do try to avoid any strenuous activity, at least whilst clothed, and I’ll lay no claims to any great strength. Raw terror does, however, have a startling effect on me and I’ve been known to toss extraordinarily heavy items aside if they stood between me and a swift escape.

Anticipating the arrival of Alain DeVeer’s hand on my flailing shin occasioned just the right level of terror. It wasn’t the thought of being dragged back in and given a good kicking that worried me—although it normally would . . . a lot. It was the idea that whilst they were kicking me, and whilst poor old Jalan was rolling about manfully taking his lumps and screaming for mercy, the Silent Sister would complete her noose, the fire would ignite, and we’d each and every one of us burn.

Whatever had stretched across my face had stopped stretching and was instead keeping me from getting any farther forwards, all its elasticity used up. It felt more like a length of wire now, cutting across my forehead and face. With my feet finding nothing to push against, I hung, one-third out, two-thirds in, thrashing helplessly and roaring all manner of threats and promises. I rather suspect Alain and his friends might have paused to have a laugh at my expense because it took longer than I expected before someone laid a hand on me.

They should have taken the matter more seriously. Flailing legs are a dangerous proposition. Fuelled by desperation I struck out and made a solid connection, booted heel to something that crunched like a nose. Someone made a noise very similar to the one Alain had made that morning when I broke the vase over his head.

The added thrust proved sufficient. The wirelike obstruction bit deeper, like a cold knife carving through me, then something gave. It felt more as though it were me that gave rather than the obstruction, as if I cracked and it ran through me, but either way I won free and tumbled out in one piece rather than two.

As victories go it proved fairly Pyrrhic, my prize being the liberty to pitch out face first with a two-storey drop between me and the flagstones. When you run out of screaming during a fall, you know that you’ve dropped way too far. Too far and too fast in general for there to be any reasonable prospect of you ever getting up again. Something tugged at me, though, slowing my descent a fraction, an awful ripping sound overriding my scream as I fell. Even so, I hammered into the ground with more than enough force to kill me but for the large mound of semisolid dung accumulated beneath the privy outlet. I hit with a splat.

I staggered up, spitting out mouthfuls of filth, roared an oath, slipped, and plunged immediately back in. Derisive laughter from on high confirmed I had an audience. My second attempt left me on my back, scraping dung from my eyes. Looking up I saw the whole side of the opera house clothed in interlocking symbols, with one exception. The window from which I tumbled lay bare, a man’s face peering from the hole I’d left. Elsewhere the black limbs of the Silent Sister’s calligraphy bound the shutters closed, but across the broken privy shutter, not even a trace. And leading down from it, a crack, running deep into the masonry, following the path of my descent. A peculiar golden light bled from the crack, flickering with shadows all along its length, illuminating both alley and building.

With more speed and less haste I found my feet and cast around for the Silent Sister. She’d rounded the corner, quite possibly before I fell. How far she had to go until completing her noose I couldn’t see. I backed to the middle of the alley, out of the dung heap, wiping the muck from my clothes to little avail. Something snagged at my fingers and I found myself holding what looked like black ribbon but felt more like the writhing leg of some nightmare insect. With a cry I tore it from me and found the whole of one of the witch’s symbols hanging from my hand, nearly reaching to the ground and twisting in a breeze that just wasn’t there—as if it were somehow trying to wrap itself back around me. I flung it down in revulsion, sensing it was more filthy than anything else that coated me.

A sharp retort returned my gaze to the building. As I watched, the crack spread, darting down another five yards, almost reaching the ground. The shriek that burst from me was more girlish than I would have hoped for. Without hesitation, I turned and fled. More laughter from above. I paused at the alley’s end, hoping for something clever to shout back at Alain. But any witticism that might have materialized vanished as all along the wall beside me the symbols started to light up. Each cracked open, glowing, as if they had become fissures into some world of fire waiting for us all just beneath the surface of the stone. I realized in that instant that the Silent Sister had completed her work and that Alain, his friends, the old man with his wine, and every other person inside was about to burn. I swear, in that moment I even felt sorry for the opera singers.

“Jump, you idiots!” I shouted it over my shoulder, already running.

I rounded the corner at speed and slipped, shoes still slick with muck. Sprawling across cobbles, I saw back along the alleyway, now lit in blinding incandescence shot through with pulsing shadow. Each symbol blazed. At the far end, one particular shadow stayed constant: the Silent Sister, ragged and immobile, still little more than a stain on the eye despite the glare from the wall beside her.

I gained my feet to the sound of awful screaming. The old hall rang to notes that had never before issued from any mouth within it down the long years of its history. I ran then, feet sliding and skittering beneath me—and out of the brilliance of that alleyway something gave chase. A bright and jagged line zigzagged along my trail as if the broken pattern sought to reclaim me, to catch me and light me up so that I too might share the fate I’d fought so hard to escape.

You would think it best to save your breath for r

unning, but I often find screaming helps. The street I had turned into from the alley ran past the back of the opera house and was well-trodden even at this hour of the night, though nowhere near as crowded as Paint Street, which runs past the grand entrance and delivers patrons to the doors. My . . . manly bellowing . . . served to clear my path somewhat, and where townsfolk proved too slow to move I variously sidestepped or, if they were sufficiently small or frail, flattened them. The crack emerged into the street behind me, advancing in rapid stuttering steps, each accompanied by a sound like something expensive shattering.

Turning sideways to slot between two town-laws on patrol, I managed a glance back and saw the crack jag left, veering down the street, away from the opera house and in the direction I’d taken. The people in the road hardly noticed, transfixed as they were by the glow of the building beyond, its walls now wreathed in pale violet flame. The crack itself seemed more than it first appeared, being in truth two cracks running close together, crossing and recrossing, one bleeding a hot golden light and the other revealing a consuming darkness that seemed to swallow what illumination fell its way. At each point where they crossed golden sparks boiled in darkness and the flagstones shattered.

I barged between the town-laws, the impact spinning me round, hopping on one foot to keep my balance. The crack ran under an old fellow I’d felled in my escape. More than that, it ran through him, and where the dark crossed the light something broke. Smaller fissures spread from each crossing point, encompassing the man for a heartbeat before he literally exploded. Red chunks of him were thrown skyward, burning as they flew, consumed with such ferocity that few made it to the ground.

Whatever anyone may say about running, the main thing is to pick your feet up as quickly as possible—as if the ground has developed a great desire to hurt you. Which it kind of had. I took off at a pace that would have left my dog-fleeing self of only that morning stopping to check whether his legs were still moving. More people exploded in my wake as the crack ran through them. I vaulted a cart, which immediately detonated behind me, pieces of burning wood peppering the wall as I dived through an open window.

I rolled to my feet inside what looked to be, and certainly smelled like, a brothel of such low class I hadn’t even been aware of its existence. Shapes writhed in the gloom to one side as I pelted across the chamber, knocking over a lamp, a wicker table, a dresser, and a small man with a toupee, before pulverizing the shutters on the rear window on my way out.

The room lit behind me. I crashed across the alleyway into which I’d spilled, let the opposite wall arrest my momentum, and charged off. The window I came through cracked, sill and lintel, the whole building splitting. The twin fissures, light and dark, wove their path after me, picking up still more speed. I jumped a poppy-head slumped in the alley and raced on. From the sound of it the fissure cured his addiction permanently a heartbeat later.

Eyes forward is the second rule of running, right after the one about picking up your feet. Sometimes, though, you can’t follow all the rules. Something about the crack demanded my attention, and I shot another glance back at it.

Slam! At first I thought I’d run into a wall. Drawing breath for more screaming and more running, I pulled away, only to discover the wall was holding me. Two huge fists, one bandaged and bloody, bunched in the jacket over my chest. I looked up, then up some more, and found myself staring into Snorri ver Snagason’s pale eyes.

“What—” He hadn’t time for more words. The crack ran through us. I saw a black fracture race through the Norseman, jagged lines across his face, bleeding darkness. In the same moment something hot and unbearably brilliant cut through me, filling me with light and stealing the world away.

My vision cleared just in time to see Snorri’s forehead descending. I heard a crack of an entirely different kind. My nose breaking. And the world went away again.

SIX

First check where my money pouch is, and pat for my locket. It’s a habit I’ve developed. When you wake up in the kinds of places I wake up in, and in the company I often pay to keep . . . well, it pays to keep your coin close. The bed was harder and more bumpy than I tend to like. As hard and bumpy as cobbles, in fact. And it smelled like shit. The glorious safe moment between being asleep and being awake was over. I rolled onto my side, clutching my nose. Either I’d not been unconscious very long, or the stink had kept even the beggars off. That and the excitement down the road, the trail of exploded citizens, the burning opera house, the blazing crack. The crack! I staggered to my feet at that, expecting to see the jagged path leading down the alley and pointing straight at me. Nothing. At least nothing to see by starlight and a quarter moon.

“Shit.” My nose hurt more than seemed reasonable. I remembered fierce eyes beneath heavy brows . . . and then those heavy brows smacking into my face. “Snorri . . .”

The Norseman was long gone. Why small charred chunks of us both weren’t decorating the walls, I couldn’t say. I remembered the way those two fissures had run side by side, crossing and recrossing, and at every junction, a detonation. The dark fracture line had run through Snorri—I had seen it across his face. The light—

I patted myself down, sudden frantic hands searching for injury. The light one had run through me. Pulling up my trouser legs revealed grubby shins with no sign of golden light shining from any cracks. But the street showed no sign of the fissure either. Nothing remained but the damage it had wrought.

I shook thoughts of that blinding golden light from my mind. I’d survived! The screams from the opera house returned to me. How many had died? How many of my friends? My relatives? Had Alain’s sisters been there? Pray God Maeres Allus had been. Let it be one of those nights he pretended to be a merchant and used his money to buy him into social circles far above his station. For now, though, I needed to put more distance between me and the site of the fire. But where to go? The Silent Sister’s magic had pursued me. Would she be waiting at the palace to finish the job?

When in doubt, run.

I took off again, along dark streets, lost but knowing in time that I would hit the river and gain my bearings anew. Running blind is apt to get you a broken nose, and since I had one of those already and wasn’t keen to find out what came next I kept my pace on the sensible side of breakneck. I normally find that showing trouble my heels and putting a few miles behind me makes things a whole lot better. As I ran, though, breathing through my mouth and catching my side where a muscle kept cramping, I felt worse and worse. A general unease grew minute by minute and hardened into a general crippling anxiety. I wondered whether this was what conscience felt like. Not that any of it had been my fault. I couldn’t have saved anyone even if I’d tried.

I paused and leaned against a wall, catching my breath and trying to shake off whatever it was that plagued me. My heart kept fluttering behind my ribs as if I’d started to sprint rather than come to a halt. Each part of me seemed fragile, somehow brittle. My hands looked wrong, too white, too light. I started to run again, accelerating, any fatigue left behind. Spare energy boiled off my skin, rattled through me, set my teeth buzzing in their sockets, my hair seeming to float up around my head. Something was wrong with me, broken; I couldn’t slow down if I wanted to.

Ahead the street forked, starlight offering just the lines of the building that divided the way. I veered from one side of the street to the other, unsure which path to follow. Moving to the left made me worse, my speed increasing, sprinting, my hands almost glowing as they pumped, head aching, ready to split, bright light fracturing across my vision. Veering right restored a touch of normality. I took the right fork. Suddenly I knew the direction. Something had been tugging at me since I picked myself up off the cobbles. Now, as if a lamp had been lit, I knew the direction of its pull. If I turned from it, then whatever malady afflicted me grew worse. Head towards it and the symptoms eased. I had a direction.

What the destination might be I couldn’t say.<

br />

It seemed to be my day for charging headlong down the streets of Vermillion. My path now followed the gentle gradient towards the Seleen where she eased her slow passage through the city. I started to pass the markets and cargo bays behind the great warehouses that fronted the river docks. Even at this hour men moved back and forth, hauling crates from mule-drawn trolleys, loading wagons, labouring by the mean light of lanterns to push the stuff of commerce through Vermillion’s narrow veins.

My path took me across a deserted marketplace smelling of fish and fetched me up against a wide expanse of wall, one of the city’s most ancient buildings, now co-opted into service as a docks warehouse. The thing stretched a hundred yards and more both left and right, and I had no interest in either direction. Forwards. My route lay straight ahead. That’s where the pull came from. A broad-planked door cracked open a few yards off and without thought I was there, yanking it wide, slipping past the bewildered menial with his hand still trying to push. A corridor ran ahead, going my way, and I gave chase. Shouts from behind as men startled into action and tried to catch me. Builder-globes burned here, shedding the cold white light of the ancients. I hadn’t realized quite how old the structure was. I charged on regardless, flashing past archway after archway each opening on to Builder-lit galleries, all packed with green-laden benches and walled with shelf upon shelf of many-leaved plants. When, about halfway through the width of the warehouse, a plank-built door opened, slamming out into my path, all I had time to think before blacking out was that hitting Snorri ver Snagason had hurt more.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

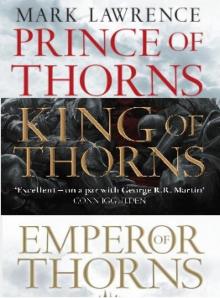

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

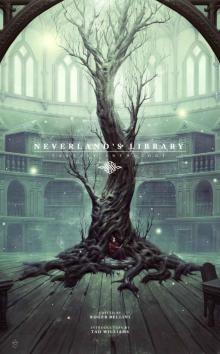

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology