- Home

- Mark Lawrence

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) Page 5

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) Read online

Page 5

And suddenly all eyes were on me. There had been times at the table that I’d forgotten I was wearing the hat. All at once it felt heavy. I had considered lying. Just telling them that it was hair loss due to anxiety. Stress alopecia they called it. I looked it up. But although I felt a wholly unwarranted degree of shame in admitting to cancer, it seemed somehow worse to declare myself to be going bald at fifteen without good reason.

‘Yeah, what about the hat, Nick?’ Mia asked, smiling.

My mouth went dry, and suddenly out of nowhere I was struggling to keep my voice steady. As if I might burst into tears at any moment or something equally stupid. ‘I didn’t come to school this Thursday, or last, because I was on an oncology ward.’

‘Onk-what-ogy?’ John snorted.

‘Ward?’ Simon frowned. ‘Like a hospital.’

‘Cancer.’ A scowl from Elton. ‘Not cool, dude. That shit’s not funny. Don’t joke about it.’

I paused. Even while sat there trying to get the words out without my voice breaking I was struck by the fact that each of them had said almost exactly what they said in my weird hospital vision.

‘I’m not joking.’ I pulled my cap off.

Silence. Just the four of them staring at my white scalp showing through thinning black hair.

Elton was the first to speak. ‘No, man . . .’ He stood from his chair, dark eyes glistening. ‘This ain’t right.’

‘Cancer?’ Simon, quiet, not looking up.

‘Not while I’m in charge.’ Against all expectations, Elton came round the table in three strides and literally dragged me out of my seat into a hug. I hadn’t been hugged by a boy before. Or a girl, come to think of it. Just Mother on rare occasions, and my two grandmothers at Christmases. I stood there, not knowing what to do with my arms, jaw locked tight against any outburst of emotion.

‘Shit.’ John realised he should say something, his face in motion as if unable to find the right expression. ‘I . . . Well . . . Shit!’ He thumped the table hard enough to make the dice dance and the figures fall over. ‘They’re going to make you better, though, right?’

‘Sure.’ I eased myself from Elton’s embrace. ‘We live in an age of miracles, don’t we? I’ve got a computer in my bedroom! Well . . . a Commodore 64 . . .’ I realised I was babbling. ‘I, uh. I gotta go.’

I started to stuff my papers and books into my bag. Nothing wanted to fit, everything at awkward angles. ‘You OK, Si?’

Simon kept his gaze on the table, brow twisted in furious concentration like when he totally disagreed with one of the game master’s rulings and was building up the head of steam required for him to object.

‘Si?’ He was chewing his cheek. Always a bad sign. ‘Earth to Simon?’ I reached for his shoulder.

‘Cancer?’ He launched himself to his feet, scattering two chairs. ‘Cancer!’ A shout that had footsteps running up the stairs. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’ Red-faced and furious. I’d only seen him like it once, years back when we teased him past breaking point on some small thing. Although he was short, Simon was almost as wide as he was tall, and when he barrelled at you there was no stopping him. ‘You’re ruining everything!’ Tears now, glistening on scarlet cheeks. I couldn’t blame him. A large part of me wanted to shout and cry and throw things about, too. But if I broke that dam open and let those emotions flow, I had no idea how I could close it again. Instead, I rammed the last few things into my bag.

‘What’s going on?’ Simon’s mum in the doorway, an apron on, hands still soapy from the dishes.

‘I’ve got to go.’ I snatched my bag and squeezed past her, everyone talking at once. ‘Sorry.’

‘Nick? Nicko!’

I made it down the stairs despite nearly tripping over Baggage and ending my dramatic exit in Accident and Emergency. A moment later I was out in the street, running.

I always felt I should be good at running. Skinny. Long legs. But no. Whatever plumbing of heart and lungs is needed for the long-distance runner . . . well, I have the other sort. Two blocks from Simon’s house, I was doubled up, leaning on a gate post, gasping for breath. A cough, and suddenly the gasping turned into retching, and I was splattering the pavement with a mixture of chocolate digestives and orange juice.

I clung to the gate, lines of drool hanging from my open mouth, deep in misery. I couldn’t blame Simon. He wasn’t wired like regular people, and it went beyond the pocket calculator in his head. He couldn’t deal with change. Even good change was bad. And bad change . . . well, that could make him lose it.

‘Jesus, Hayes! The fuck you doin’?’

It seemed so far beyond reasonable that Michael Devis should happen upon me in that moment that I ignored the voice and kept my head down.

‘That’s disgusting. Messing up the street.’

I wiped my mouth, continuing to ignore him.

‘Heard you bumped into Ian Rust the other day. Chucked your shit in the gutter.’

I straightened up, trembling, though whether from fear, anger, or puking I couldn’t tell.

‘I should empty your crap on that lot.’ Devis nodded to the glistening mess at my feet. He was just starting to reach for the sports bag on my shoulder when someone came past me. A dark figure. And, in the same motion, swung a fist right into Devis’s mouth. A real haymaker punch.

Devis staggered back clutching his face, then fell on his arse. He groaned and his hands came away scarlet from his mouth. The newcomer loomed over him. My first thought had been that Elton had caught up with us, but it was the bald guy.

‘You better run, because I enjoyed that and want to do it again.’ He kicked Devis’s outstretched foot. ‘Scram!’

Devis got to his feet, clutching his face again, half-dazed. The man took a quick step forward and Devis turned to run.

‘You’re a fucking nutter.’ He got to the corner. ‘I’ll have the police on you, you bastard!’

The man made to run after him and Devis took off.

‘Wow, that felt good!’ The man turned back to me. ‘I’ve been waiting twenty-five years to do that.’ He shook his hand. ‘Hurt like fuck, though!’

I stood for a moment, mouth open, finding no words. He was tall, a couple of inches taller than me, six two, six three maybe. Not properly old. Forty perhaps. Something about him looked disturbingly familiar.

‘Who . . . ? Why . . . ?’ I felt dizzy. The times I’d seen the man before all tried to crowd in on me at once. At the hospital, the park, the window. I reached for the wall, needing support. ‘Why did you do that?’

‘Why?’ He flexed his hand, winced, then grinned. ‘To gain your trust, of course.’

CHAPTER 5

‘He what?’

‘Punched Michael Devis square in the mouth.’

‘No way?’ John stood up from the end of my bed as if the idea was too much to take sitting down. ‘I saw him today in school. The side of his face is all purple.’

‘Good. He deserves it.’

‘Still . . .’ John sat down again. I winced. ‘The guy’s bat-shit crazy, right?’

‘Off the scale.’ I pushed a stray sweater over the pile of quantum mechanics books on my bedside table.

‘Well, if you’re going to have a stalker, then that’s the type to have: A Devis-thumping one.’ John shook his head and looked around my room. The bed took half the space. John’s bedroom was the size of a barn and filled with cool stuff. He had a Viking battle-axe on his wall, and a Syrian helm with a chainmail coif on a stand. ‘You coming back to school this week?’

‘Maybe on Friday.’ I shrugged.

‘Did he look crazy? I mean close up. Twitchy?’

‘Uh. Not really.’ He’d looked like my father. It wasn’t him. There were enough differences for that to be clear even if the funeral didn’t settle the matter. But he had looked enough like him to be a secret uncle I’d never been told about.

‘What did he say?’

‘Crazy stuff. Weird things.’ He told me that we would speak ag

ain in a week. He’d said something about needing time for the echoes to settle before we could talk properly. I’d been hurting and disoriented, so I couldn’t remember everything. He told me his name, though: Demus.

‘I’m Demus, you’re Nick.’ The bald guy had raised a hand to ward off questions. ‘I know everything . . . We’ll talk next week when you’re ready to listen. Until then, why not stay off school and do your homework?’

‘Homework?’ I’d echoed stupidly.

‘Bone up on quantum mechanics. Particularly Everett’s many-world interpretation. You can get the books at the Imperial College library. Speak to Professor James in the maths department. Show him that thing with knots in n-space topologies. He’ll like that.’

‘How do you—’

‘I know everything. I just told you that. Tell Mother you’re sick and can’t go to school. It’s not like she can argue with that.’ He’d reached out to press a piece of folded paper into my hand. ‘And memorise these numbers. That’s the most important part.’

‘Uh?’ I looked at the white square in my palm.

‘When the time comes, make a show of it. You need to get the others on board.’ And with that he had hurried off back the way he came. I’d taken a few steps after him, but another bout of nausea brought me to my knees, and when it let me go Demus was gone.

‘Nick?’ John snapped his fingers in front of my face.

‘W . . . what?’

‘Spaced out on me there, buddy.’

‘Sorry. Just tired, I guess.’ I’d been up late, reading.

‘Yeah.’ John stood again. ‘Look, I better go. Don’t want to wear you out. I already had the lecture from your mum!’ He picked up his school briefcase. ‘Mia was asking about you, you know?’

‘You called her?’ It was stupid, but I didn’t want John talking to her. She had been out of my league even before I started vomiting and shedding, and I hadn’t got a clue what I would do even if John stepped back and waved me on. But still. Even though he was my friend, a small mean voice complained that he already had every good thing. Mia shouldn’t be on his list of acquisitions, too.

‘She called me!’ He grinned, showing perfect white teeth that I felt an unaccountable urge to punch. ‘Anyway. Gotta go. And you, you have to show on Saturday or we’ll all come here and crowd in like sardines.’ He got up, then paused at the door. ‘Oh, I almost forgot. You’ll like this one. In other news: Ian Rust got himself expelled! Devis won’t know what to do with himself with his mentor gone.’

‘Expelled?’ That really did bring a smile to my face. ‘What did he do?’

John frowned at that. ‘Twisted David Steiner’s arm up behind his back so far that something snapped.’

‘Something?’ My stomach went cold.

‘A bone.’

‘And nobody tried to stop him?’

‘Mr Roberts did. But Rust just broke Steiner’s arm anyway, and then pulled a knife on Roberts.’

‘Holy crap! Rust’s a fucking lunatic.’ Mr Roberts was a PE teacher, over six feet tall and packed with muscle.

‘Indeed.’ John nodded. ‘The police were called, but Rust had vanished by the time they came. Besides, they won’t hold him, just set a court date or something . . .’

When John had gone I turned on my reading lamp and returned to my textbooks. It was that or go downstairs to watch Dallas with Mother. She said it was her guilty pleasure, and it was true that it was about the only programme that would convince her to watch something other than BBC2. Even the instigation of a fourth channel hadn’t managed to do that!

I had to admit that quantum mechanics was clever stuff. Most of it danced to its own tune, but there was still enough fundamental mathematics underlying all the pretty manipulations to keep me interested.

I’d done what Demus said to do. After all, he had driven his fist into Devis’s over-loud mouth for me. And what else was there to do? I’d been presented with a mystery. I could focus on that, or I could worry about leukaemia chewing its way through the marrow of my bones. No contest really. Quantum mechanics wasn’t exactly easy, but it unravelled itself a lot more willingly than the strangeness that Demus constituted. Who the hell was he? Why had he singled me out? And why now?

Getting off school was easy. Escaping the house, harder. I’d taken the tube to South Kensington and hobbled my way past the Natural History Museum to Imperial College, an ugly set of buildings poured out of concrete mixers in the sixties, right behind the Royal Albert Hall.

I’d tried to get into the library first, picking up a leaflet from the main reception, but was escorted from the premises by an efficient woman with grey-streaked hair scraped into a tight bun and those angular glasses that they must force librarians to wear. Apparently, teenagers in Joy Division T-shirts were not welcome, and I should be in school. Though how she could distinguish me from the students, I didn’t know. And what kind of rowdy youth plays truant to come to a university physics library?

Professor James had seemed rather surprised to see me at his door. He asked me if I were lost. I answered by asking him if he had considered the Ryberg Hypothesis in non-Euclidian manifolds above five dimensions, because it suddenly became provable, and that fact had powerful implications for high order knot theory. After that, he was all mine.

To me the most interesting thing was, for once, not about the mathematics, but about the fact that Demus had known both that I was aware of the professor’s work in the area, and that I’d made several advances on what James had published.

‘This is quite extraordinary, young man.’ The professor sat down heavily, leaning back from our pages of scribbling. He had a habit of tugging at himself when he concentrated and now looked as if he’d been pulled backwards through a hedge. ‘Nicholas Hayes, did you say?’

‘Nick.’

He pulled at the corner of his moustache. ‘No relation to Alfred Hayes, of course?’

‘My father.’

‘Ah . . .’ He seized at that like a drowning man. ‘This is his unpublished work? I must say, I’m tremendously impressed that you understand any of it, Nick. What are you, first year, second?’

‘Actually, I’m not at the university yet. Which, uh, brings me to the real reason for my visit. I need to borrow your library card. Also, if you could call down to the librarian to expect me, that would help a lot.’

All I had to do was promise to come back with any more of my father’s papers that I might find, and Professor James couldn’t get his card into my hands quickly enough.

‘Nick?’ A knock at my bedroom door. I lifted my head from Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals by Richard Feynman, the world’s greatest living expert on the subject. Another knock. I had the feeling there might have been several already that I failed to notice.

‘Yes?’

Mother opened the door. ‘You have another visitor.’ She sounded a little odd.

‘Hi, Nick!’ Mia squeezed past Mother, who had positioned herself as guardian of the doorway. ‘I bought chocolate brazils. They’re kinda like grapes. Only chocolate, and . . . not.’ She put the box beside me on the bed.

‘Uh . . .’ I blinked up at her. She wasn’t in uniform. I’d assumed she went to Elton’s school, but had never asked. Instead, she was gothed-up to eleven: black, black, more black, and some zips; black-circled eyes in a white face, lips a very dark red. ‘Hi.’

Mother stayed where she was, her smile fixed in that way we Brits use to show we wholly disapprove of something.

‘Hi.’ I said it again because suddenly it was all I had. I also became painfully aware that my woolly hat was just beyond arm’s reach, and that putting it on now would be too obvious. Instead, I had to treat her to the full patchwork horror show of my scalp.

‘Hi,’ Mia said. And then, just as I thought we might be locked in this death-spiral of greeting for the rest of our lives, ‘What you reading?’

Instead of answering, I looked pointedly over her shoulder at Mother, who had already outstayed the

sociably acceptable linger limit by a factor of at least three. ‘I’d love a drink, Mum.’

She missed a beat at ‘Mum’ but rallied herself admirably. ‘Orange ju—’

‘Tea, please.’ I’d never asked for tea before.

‘Of course.’ Her smile re-fixed itself. ‘And . . . Mia? Would you like some . . . tea?’

‘Coffee, if you have it.’ Mia smiled. ‘White with two sugars.’

Mother retreated. I waited until I heard her footsteps on the stairs.

‘Quantum mechanics.’ I held up the book.

‘Cool.’ Mia sat on the bed. Closer than friends normally sit next to friends. She smelled of patchouli oil. I liked it. ‘What’s that about then?’

‘Well . . . it’s about everything, really. It’s the most accurate and complete description of the universe we’ve ever had. It’s also completely bonkers.’ I hesitated. I was pretty sure this wasn’t what you were supposed to talk about when girls came to visit.

‘More bonkers than general relativity?’ Mia took the book from the death grip I had it in. ‘The twins paradox is hard to beat.’

With a sigh, I relaxed. She was one of us! The magical power of D&D to draw together people who knew things. Who cared about questions that didn’t seem to matter.

‘Way weirder.’ Mia was right, the twins paradox was hard to beat. When Einstein showed the world that time was made of rubber and could be stretched for one person and squeezed for another until their lives were years out of kilter . . . that had been pretty strange. But even Einstein had balked at the cosmic strangeness quantum mechanics throws at us. ‘I’ve been looking at the many worlds interpretation.’

Mia started to open the box of chocolate brazils. ‘Go on.’

‘Well. The thing is, quantum mechanics is chock full of crazy, but every prediction it makes is perfect to as many decimal places as we can measure. Loads of our technology is built on it. Consequently, we just have to swallow the madness.’

‘Right.’ Mia pushed a chocolate past her lips, then offered the box to me.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

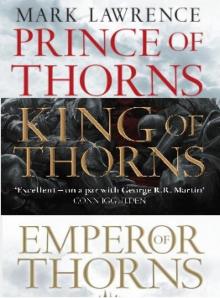

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

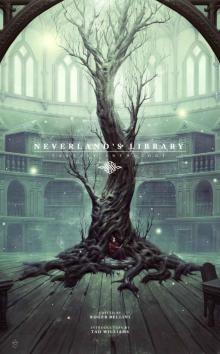

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology