- Home

- Mark Lawrence

King of Thorns Page 4

King of Thorns Read online

Page 4

Rike started to laugh. Not that “hur, hur, hur” of his that sounds like another kind of anger, but a real laugh, from the belly. “It’s like…It’s like…” He couldn’t get the words out.

The others couldn’t hold back. Sim and Maical cracked first. Grumlow snorting through the drowned-rat moustache he’d been working on. Then Red Kent and at last even Row, laughing like children. Gog looked on, astonished. Even Gorgoth couldn’t help but grin, showing back-teeth like tombstones.

The clown fell over and kept on stamping the air. Rike collapsed with it, thumping the ground with his fist, gasping for breath.

The clown slowed, then stopped. There’s a blue-steel spring inside that you wind tight with a key. And when it’s finished stamping and crashing, the spring is loose again.

“Burlow…Burlow should have seen this.” Rike wiped the tears from his eyes. The first time I’d heard him mention any of the fallen.

“Yes, Brother Rike,” I said. “Yes, he should.” I imagined Brother Burlow laughing with us, his belly shaking.

We made our moment then, one of those waypoints by which a life is remembered, the Brotherhood remade and bound for the road. We made our moment—the last good one. “Time to go,” I said.

Sometimes I wonder if we all don’t have a blue-steel spring inside us, like that dena of Gorgoth’s coiled tight at the core. I wonder if we don’t all go stamping and crashing, crashing and stamping in our own little circles going nowhere. And I wonder who it is that laughs at us.

6

Four years earlier

Three months previously I had entered the Haunt alone, covered in blood that was not my own and swinging a stolen sword. My Brothers followed me in. Now I left the castle in the hands of another. I had wanted my uncle’s blood. His crown I took because other men said I could not have it.

If the Haunt reminds you of a skull, and it does me, then the scraps of town around the gates might be considered the dried vomit of its last heave. A tannery here, abattoir there, all the necessary but stinking evils of modern life, set out beyond the walls where the wind will scour them. We were barely clear of the last hovel before Makin caught us.

“Missing me already?”

“The Forest Watch tell me we have company coming,” Makin said, catching his breath.

“We really should rename the Watch,” I said. The best the Highlands could offer by way of forest was the occasional clump of trees huddled miserably in a deep valley, all twisted and hunched against the wind.

“Fifty knights,” Makin said. “Carrying the banner of Arrow.”

“Arrow?” I frowned. “They’ve come a ways.” The province lay on the edge of the map we had so recently rolled up.

“They look fresh enough by all accounts.”

“I think I’ll meet them on the road,” I said. “We might get a more interesting story out of them as a band of road-brothers.” The truth was I didn’t want to change back into silks and ermine and go through the formalities. They would be heading for the castle. You don’t send fifty men in plate armour for a stealth mission.

“I’ll come with you,” Makin said. He wasn’t going to take “no” this time.

“You won’t pass as a road-brother,” I said. “You look like an actor who’s raided the props chest for all the best knight-gear.”

“Roll him in some shit,” Rike said. “He’ll pass then.”

We happened to be right by Jerring’s stables and a heap of manure lay close at hand. I pointed to it.

“Not so different from life in court.” Makin grimaced and threw his robe into the head-cart. Maical had hitched it to the grey out of habit.

When the captain of my guard looked more like a hedge-knight at the very bottom of his luck, we moved on. Gog rode with me, clutching tight. Gorgoth jogged along, for no horse would take him, and not just because of his weight. Something in him scared them.

“Ever been to Arrow, Makin?” I asked, easing my horse upwind.

“Never have,” he said. “A small enough principality. They breed them tough down there though, by all accounts. Been giving their neighbours a headache for years now.”

We rode on without talk for a while, just the clatter of hooves and the creak of the head-cart to break the mountain silence. The road—or trail if I’m honest, for the Builders never worked their magic in the Highlands—wound its way down, snaking back and forth to tame the gradients. As we dropped I started to realize that in the low valleys it would be spring already. Even here a flash of green showed now and again and set the horses nosing the air.

We saw the knights’ outrider an hour later and the main column a mile farther on. Row started to turn off the trail.

“I’ll say when we turn aside and when we stand our ground, if it’s all the same to you, Brother Row.” I gave him a look. The Brothers had started to forget the old Jorg—been too long lazing around the Haunt, left too long to their own wickednesses.

“There’s a lot of them, Brother Jorg,” said Young Sim, older than me of course but still with little use for a razor if you discounted the cutting of throats.

“When you’re making for the king’s castle it’s bad manners to cut down travellers on the way,” I said. “Even ones as disreputable as us.”

I rode on. A pause and the others followed.

The next rise showed them closer, two abreast, moving at a slow trot, a pair of narrow banners fluttering in the Renar wind. No rabble these, table-knights from a high court, a harmony to their arms and armour that put my own guard to shame.

“This is a bad idea,” Makin said. He stank of horse-shit.

“If you ever stop saying that I’ll know it’s time to start worrying,” I said.

The men of Arrow continued their advance. We could hear their hooves on the rock. I had an urge to rest in the middle of the trail and demand a toll. That would have made a tale, but perhaps too short a one. I settled for pulling to the side and watching as they drew closer. I cast an eye over our troop. An ugly lot, but the leucrotas won the prize.

“See if you can’t hide behind Rike’s beast, Gorgoth,” I said. “I knew that plough horse would come in useful.”

I took the knife from my belt and started to work the dirt from under my fingernails. Gog’s claws dug in beneath my breastplate as the first men reached us.

The knights slowed their horses to a walk as they came near. A few turned their heads but most passed without a glance, faces hidden behind visors. At the middle of the column were two men who caught the eye, or at least their armour did, polished to a brilliance, fluted in the Teuton style, and scintillating with rainbow hues where the oiled metal broke the light. A hound ran between their horses, short-haired, barrel-chested, long in the snout. The leftmost of the pair raised his hand and the column stopped, even the men in front of him, though there seemed no way they could have seen him.

“Well now,” he said, both words precise and tightly wrapped.

He took his helm off, which seemed a foolish thing to do when he might be the target of hidden crossbows, and shook his head. Sweat kept his blond hair plastered to his brow.

“Good day, Sir Knight,” I said and nodded him a quarter of a bow.

He looked me up and down with calm blue eyes. He reminded me of Katherine’s champion, Sir Galen. “How far to Renar’s castle, boy?” he asked.

Something in me said that this man knew exactly how far it was, as crow flies and cripple crawls. “King Jorg’s castle lies a good ten miles yonder.” I waved my knife along the trail. “About a mile of it up.”

“A king is it?” He smiled. Handsome like Galen too, in that square-jawed blond manner that will turn a girl’s head. “Old Renar didn’t count himself a king.”

I started to hate him. And not just for the pun. “Count Renar held only the Highlands. King Jorg is heir to Ancrath and the lands of Gelleth. That’s enough land to make a king, at least in these parts.”

I made show of peering at the fellow’s breastplate. He had

dragons there, etched and enamelled in red, each rampant, clutching a vertical arrow taller than itself. Nice work. “Arrow is it you’re from, my lord?” I asked. Not waiting for an answer I turned to Makin. “Do you know why that land is named Arrow, Makin?”

He shook his head and studied the pommel of his saddle. The need to say “this is a bad idea” twitched on his lips.

“They say it’s called Arrow because you can shoot one from the north coast to the south,” I said. “From what I hear they could have called it Sneeze. I wonder what they call the man who rules there.”

“You know a lot about heraldry, boy.” Eyes still calm. The man beside him moved his hand to his sword, gauntlet clicking against the hilt. “They call the man who rules there the Prince of Arrow.” He smiled. “But you may call me Prince Orrin.”

It seemed rash to be riding into another’s realm with fifty men, even fifty such as these. The very thing I had decided against for my own travels.

“You’re not worried that King Jorg will take the opportunity to thin the field in this Hundred War of ours?” I asked.

“If I were his neighbour, maybe,” the Prince said. “But killing me or even ransoming me to my enemies would just make his own neighbours more secure and better able to harm him. And I hear the king has a good eye for his own chances. Besides, it would not be easy.”

“I thought you came looking for a count, but now it seems you already know about King Jorg and his good eye,” I said. He came prepared, this one.

The Prince shrugged. He looked young when he did it. Twenty maybe. Not much more. “That’s a handsome sword,” he said. “Show it to me.”

I’d wrapped the hilt about with old leather and smeared that with dirt. The scabbard was older than me and shiny with the years. Whatever my uncle’s sword had been, it wasn’t handsome now. Not until I drew it and showed its metal. I considered throwing my dagger. Old blondie might not see so clear with it jutting out of his eye socket. He might even have a brother at home who’d be pleased to be the new Prince of Arrow and owe me a favour hereafter. I could see it in my mind’s eye. The handsome Prince with my dagger in his face, and us racing away across the slopes.

I’m not given to should haves. But I should have.

Instead I stowed the knife and drew my uncle’s sword, an heirloom of his line, Builder-steel, the blade taking the light of the day and giving it back with an edge.

“Well now,” Prince Orrin said again. “An uncommon sword you have there, boy. From whom did you steal it?”

The mountain wind blew cold, finding every chink in my armour, and I shivered despite the heat pulsing from Gog at my back. “Why would the Prince of Arrow come all the way to the Renar Highlands with just fifty knights, I wonder?” I dismounted. The Prince’s eyes widened at the sight of Gog left in the saddle, half-naked and striped like a tiger.

I stood on one of the larger rocks by the roadside, on foot to show I had no running in me.

“Perhaps such reasons are not for a bandit child by the roadside clutching a stolen sword,” he said, still maddeningly calm.

I couldn’t argue with the “stolen” so I took offence against the “child.” “Fourteen is a man’s age in these lands and I wield this sword better than any who held it before me.”

The Prince chuckled, gentle and unforced. If he had studied a book devoted to the art of infuriating me he could have done no better job. Pride has ever been my weakness, and occasionally my strength.

“My apologies then, young man.” I could see his champion frown at that, even behind his visor. “I travel to see the lands that I will rule as emperor, to know the people and the cities. And to speak with the nobles, the barons, counts…and even kings, who will serve me when I sit upon the empire throne. I would win their service with wisdom, words and favour, rather than with sword and fire.”

A pompous enough speech perhaps, but he had a way with words this one. Oh, my brothers, the way he spoke them. A magic of a new kind, this. More subtle than Sageous’s gentle traps—even that heathen witch with his dream-weaving would envy this kind of persuasion. I could see why the Prince had taken off his helm. The enchantment didn’t lie in the words alone but in the look, in the honesty and trust of it all, as if every man who heard them was worthy of his friendship. A talent to be wary of, maybe more potent even than the power Corion used to set me scurrying across empire and to steer my uncle from behind his throne.

The hound sat and licked the slobber from its chops. It looked big enough to swallow a small lamb.

“And why would they listen to you, Prince of Arrow?” I asked. I heard a petulance in my voice and hated it.

“This Hundred War must end,” he said. “It will end. But how many need drown in blood before the peace? Let the throne be claimed. The nobles can keep their castles, rule their lands, collect their gold. Nothing will be lost; nothing will end but the war.”

And there it was again. The magic. I believed him. Even without him saying so I knew that he truly sought peace, that he would rule with a fair and even hand, that he cared about the people. He would let the farmers farm, the merchants trade, the scholars seek their secrets.

“If you were offered the empire throne,” he said, looking only at me, “would you take it?”

“Yes.” Though I would rather take it without it being offered.

“Why?” he asked. “Why do you want it?”

He shone a light into my dark corners, this storybook prince with his calm eyes. I wanted to win. The throne was just the token to demonstrate that victory. And I wanted to win because other men had said that I may not. I wanted to fight because fighting ran through me. I gave less for the people than for the dung heap we rolled Makin in.

“It’s mine.” All the answer I could find.

“Is it?” he asked. “Is it yours, Steward?”

And in one flourish he showed his hand. And showed my shame. You should know that the men who fight the Hundred War, and they are all men, save for the Queen of Red, fall from two sides of a great tree. The line of the Stewards, as our enemies call us, trace the clearest path to the throne, but it is to the Great Steward, Honorous, who served for fifty years when the seed of empire failed. And Honorous sat before the throne rather than on it. Still, a strong claim to be heir to the man who served as emperor in all but name is a better case for taking that throne than a weak claim to be heir to the last emperor. At least that’s how we Stewards see it. In any case I would cut myself a path to the throne even if some bastard-born herder had fathered me on a gutter-whore—genealogy can work for me or I can cut down the family tree and make a battering ram. Either way is good.

Many of the line of Stewards are cast in my mould: lean, tall, dark of hair and eye, quick of mind. Even our foes call us cunning. The line of the emperor is muddied, lost in burning libraries, tainted by madness and excess. And many of the line, or who claim it, are built like Prince Orrin: fair, thick of arm, sometimes giants big as Rike, though pleasing on the eye.

“Steward is it now?” I rolled my wrist and my sword danced. His hound stood up, sharp, without a growl.

“Put it away, Jorg,” he said. “I know you. You have the look of the Ancraths about you. As dark a branch of the Steward tree as ever grew. You’re all still killing each other so I hear?”

“That’s King Jorg to you,” I said, knowing I sounded like a spoiled child and unable to help it. Something in Orrin’s calm humour, in the light of him, cast a shadow over me.

“King? Ah, yes, because of Ancrath, and Gelleth,” he said. “But I’m told your father has named young Prince Degran his heir. So perhaps…” He spread his hands and smiled.

The smile felt like a slap in the face. So Father had named the new son he’d made with his Scorron whore. And gifted him my birthright. “And you’re thinking to give him the Highlands too?” I asked. Keeping the savage grin on my face however much it wanted to slide away. “You should know that there are a hundred of my Watch hidden in the rocks ready to s

lot arrows through the gaps in that fancy armour, Prince.” It might even be true. I knew that at least some of the Watch would be tracking the knights.

“I’d say it was closer to twenty,” Prince Orrin said. “I don’t think they’re mountain men, are they? Did you bring them out of Ancrath, Jorg, when you ran? They’re skilled enough, but proper mountain men would be harder to spot.”

He knew too much, this prince. It was seriously starting to annoy. And as you know, being angry makes me angry.

“In any case,” he carried on as if I weren’t about to explode, as if I weren’t about to ram my sword entirely through his body, “I won’t kill you for the same reason you won’t kill me. It would replace two weak kingdoms with a stronger one. When the road to the empire throne, to my throne, leads me here, I would rather find you and your colourful friends terrorizing the peasants and getting drunk, than find your father or Baron Kennick keeping order. And I hope that by the time I arrive you will have grown wiser as well as taller, and open your lands to me as emperor.”

I jumped from my rock and the hound stood in my path quicker than quick, still no growl but way too many teeth on display, all gleaming with slobber. I fixed its eyes, which is a good way to get your face bitten off, but I meant to threaten the beast. Holding my sword by hilt and blade, flat side forward, I took another step, a snarl rising in me. I had a hound once, a good one that I loved, before such soft words were taken from me, and I had no wish to kill this one. But I would. “Back.” More growl than word. My eyes on his.

And with ears flat to its head the beast whimpered and skulked back between the horses’ legs. I think it sensed the death in me. A bitter meal, that necromancer’s heart. Another step away from the world. It sometimes seems I stand three steps outside the lives of other men. One for the heart. One for the thorn bush. And perhaps the first for that dog I remember in dreams.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

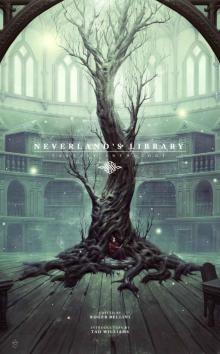

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology