- Home

- Mark Lawrence

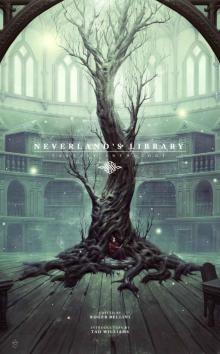

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Page 32

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Page 32

The tapestry grew still beneath my soft sounds and as the gentle memories of my days with Bernardo cascaded over them, they recalled their own individuality. One by one, the souls disentangled themselves from each other and crept onto my back. They clung to my scales until I was cloaked in hues of blues and blacks and the purple shades of grief.

Salvador’s murdered child took the place nearest my heart.

#

The centuries pass over us in our saltwater chambers. Sometimes I rise to the surface and take my human form, but I never rest in one place for too long. If I do, I fear Adriana will locate us. I have yet to find a way to destroy her, but I have cheated her.

When the souls become restless or frightened, I calm them with melodies and sing of glittering tears on the Alboran Sea, of sand, and miracles. I sing to them of love, crystal, and stone, and they quiet so we might hide once more.

Yesterday, I listened to the souls and discovered one missing; Esteuan’s voice no longer joins with the others. Somehow Adriana has found a way past my defenses. As if in answer to my fear, the waves wash a toy into my cave, a small hand-carved dragon with scales tinted blue and green. The dragon’s back is broken and the eyes are gouged out. A shiver runs through me, and I turn my face to the darkness.

She is coming and though she is never what she seems, neither am I; not anymore. I’ve taught myself the deep songs of the earth and the mysteries of shape-shifting.

My name is Alejandro.

I am Emmanouel.

And I remember my song.

A Tune from Long, Long Ago

Don Webb

In the late nineteenth century obsessive German minds began the cataloging of all human knowledge. After all, almost everything that would ever be known was already almost known. The wise thing to do then was to collect that knowledge and catalog it. Thomas Mueller was an obsessive German that impressed his equally obsessive comrades. Working in the new field of Musikwissenschaft, Mueller began a complete catalog of every Hungarian folk tune. He began his collection in his twenties and continued into his seventies and on until the disaster of 1914.

JOHN SPENCER PAUSED after typing the above words. He could’ve done the happy dance in his tiny third floor apartment overlooking Congress. He had found the perfect dissertation topic—fairly well researched (in German), almost unnoticed in English and with a truly spooky ending. Best of all, a research assistant at the Harry Ransom Center had found the sheet music associated with the “doomed” concert of 1914—a collection long thought lost. It even contained the Hexenlied or “Witch’s Song.” He could create popular articles based off of this for years, as well perfectly respectable academic papers. Mueller had worked through decades. His work was exemplary in showing the changes from Adler (and even pre-Adler) methodology toward the beginning of modern ethno-musicality. There were grants, professorships, and interviews at Halloween for this one. He made himself a glass of hot chocolate from powder and microwaved water. He sat down to type some more. He hadn’t noticed that he had also begun to hum.

#

Thomas Mueller arrived in the village of Stregoicavar by carriage on a perfect late spring evening, when the air in the mountains bore the scents of a hundred types of wildflower. The sun had retreated behind the mountains, leaving the western sky a deep regal purple, and the bright stars were claiming the sky. The inn had a pleasing goulash, a fine local beer and talkative locals. Mueller had scarcely tucked into his supper when locals began approaching him.

“You are the professor that pays money to hear old songs, are you not?”

After three decades of research, Mueller was accustomed to this. Most of the informants would have nothing new to sing for him. He had encountered songs derived from medieval church music, songs from the Folies Bergère which had somehow made their way into the back country of the Hungarian hills, patriotic clap-trap. But original folksongs were still hidden in these remote villages—and one with as promising a name as “Witch-Town” would surely hold some gems. His offer never varied. A few coppers for each song, but a silver fillér for a new song that he would write down. The first hour gave him nothing new, but was entertaining. Someone sent for the old men and women, who were sure to know. The silver pouch was opened – firstly a ballad of the fight between Count Boris Vladinoff and the Turks, then a creepy tune about the original inhabitants of Witch-Town and how the honest Hungarians killed them off, finally a song about the Devil’s Keep where Satan in the form of a giant toad still appeared.

“I could sing you a song that you will never have heard.” Said a red faced old man, clearly fond of strong drink. “But it will cost you more than a fillér.”

Everyone became silent.

Another silver haired man spoke up, “Pay no attention to my brother. He is a drunk who cannot sing.”

The conversation in the room shifted from German to Hungarian, Herr Mueller acted as though he could not speak Hungarian. He wanted to know what the villagers said to one another. He kept a quiet smile on his face as he feigned ignorance.

“Stefan, do not sing the witch ballad. We have worked hard to erase from our village. What if a pregnant woman overheard it?”

“Look around you, do you see any pregnant women? Besides what do I care if a German professor hears the song? Maybe it will make me forget it. Maybe he can carry it away from here. Even though our grandfathers’ grandfathers cleared the land here, we are under the thrall of the dark people that lived here. Let him hear it!”

“Do what you want Stefan but don’t do it here,” said the brother.

The innkeeper had been summoned during this exchange. A younger stout with hardly any gray in his hair, he looked like a small bear.

“Stefan Gyori. I forbid you to sing the Witch’s Song in my inn. This spot is clean. My grandfather kept it so, my father kept it so, I will keep it so. I have managed my whole life to hear not a note, not a word of the witches’ ballad. And I will die clean with no mortgage on my soul.”

There was agreement from several of the men and women. Stefan Gyori shrugged, and then addressed Mueller in German.

“Mein Herr. My neighbors are a superstitious lot. They fear that the song I would sing would bring bad luck upon this fine inn, much as breaking a mirror.”

Mueller replied, “Perhaps you could sing it to me elsewhere? Unless you fear it will summon the devil.” He smiled at the last part, he had to fight superstition often in his quest for folk-music.

Stefan Gyori smiled back, “No mein Herr, I am not as superstitious as my countrymen. I will gladly sing this song anywhere – crossroads, cemetery, you name it.”

An old woman, who had set by the fire and said nothing all night, had a challenge for Stefan. “Oh really Stefan Gyori, would you sing it by the Black Stone?”

Gyori’s red face blanched, but in a voice only slighter higher than he had been using, “I fear nothing. I would sing it by the Black Stone.”

The silence that had fallen before was nothing compared to the silence that greeted this remark, Mueller could not have been more pleased.

Gyori ended the silence with, “Of course because of the rarity of the song, I must ask for fifteen Krona.”

“I could pay you ten,” said Mueller.

“It must be fifteen. After all mein Herr, no one else will sing it for you.”

Certainly the fear showing in the eyes of the room agreed with that pronouncement.

“Fifteen then, but I want to hear it sung by this Black Stone.”

“I will sing tomorrow, in the sunlight.”

“I thought you were not superstitious.”

“I don’t fear lightning either, but I don’t carry metal bars around during a thunderstorm.”

#

John’s roommate, Chand Svare Ghei, was fast at work on his laptop. They had a graduate school meal. Two bottles each of local craft beer (Mad Meg from Jester King) and two packages of “Oriental Flavor” top ramen (with margarine for richness). It was Tuesday night; the sounds of a single street

guitarist came in their window. John was writing a description of Mueller’s methods in dealing with informants. Chand got up and closed the window – perhaps with a little anger.

After a few minutes Chand said, “Can you stop humming? I am trying to write some code and your humming is bugging the shit out of me.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t notice. How’s the second level going?”

“The game part is great, the team is really slow delivering the graphics, and I’m stuck with sound.”

“Well if you need help with the music –”began John.

“Yes, I know you’re a musicology major. You say that every damn time.”

They went back to work.

Fifteen minutes later Chand said, “Since you can’t be quiet, I’m going to finish this over at the PLC.”

He slammed the door on the way out.

Definitely need a new roommate next semester.

#

“This village had a very different sort of folk than it has now. It was a dark and bad place once with a different name.” said Stefan Grori as he walked Thomas Mueller away from the inn.

It was a bright day with the sun high in the sky, contented cows munching on green grass, birds busy with nest building in the hedgerows.

“What was its name?”

“Xuthltan. They were not Magyars. They were not Christians. They engaged in dark practices – devil worship, it was said.”

“The Witch’s Song is about them?” asked Mueller.

“It is from them.”

“But I thought the Magyars killed them?”

“Most of them were killed in two raids. But some of the women were kept as bondmaids. They raised the children of the noble families and they taught them the song.”

“The song teaches a pagan story?” asked Mueller.

“Who knows what it teaches? We don’t understand the language. It makes you see things, it makes you know things. And if a woman that is with child hears the song, her children are born horribly deformed. Of course it took years to figure this out. We took the servants—old hags by then—and burned them in the village square. But the song lives on.”

They arrived at a patch of land that knew no green grass. Mueller thought of the “blasted heath” in Macbeth. A spindly black stone – damned monolith rose in the center of the desolation. It was octagonal in shape, some sixteen feet in height and about a foot and a half thick. The surface was thickly dinted, as if savage efforts had been made to demolish it; but the hammers had done little more than to flake off small bits of stone and mutilate the characters which once had evidently marched up in a spiraling line round and round the shaft to the top. Mueller disliked the characters at once. He was about to tell Stefan he need not sing, when the man began his eldritch lullaby.

It was full daylight and a warm day, yet Mueller felt cold as he heard the tones. He stopped Stefan and pulled forth his tablet. He was a man of science after all. He would record the notes. As he did so, he became dizzy and numb. It seemed that part of him was not standing in his body, but on a vast plane with a darkling purple sky. He stood before a vast pit, and something was moving in the misty depths below. It was going to show itself. There were others around him – strange caricatures of the human form with extra eyes or limbs. Or fewer than they should have – as if life here were ruled by asymmetry, much as on Earth it is ruled by symmetry. Suddenly the vision stopped, he was covered in a cold sweat. Stefan had his hand out.

“You pay me now.”

#

Chand didn’t come back until seven-thirty the next day. John was showering. He was the TA for a music theory course that was early enough in the morning to weed out the less determined underclassmen.. He stayed in the shower until Chand slammed the door shut. John got out quietly and began getting dressed. As he headed out the door, Chand yelled at him, “It’s okay. I’m not mad at you. I got inspired and finished the sound for level two. It’s okay, bro, I was just grumpy about deadlines.”

#

It was twenty years later and Mueller had taken to making long walks in Berlin. The city with its endless smoke and noise and excitement could distract him from the tune which had haunted his thoughts more and more. His hair was shock white, his face wrinkled; his frame thin. That he had been a well-respected Professor as short as five years ago, no one would have guessed. He wore his clothes for too long without having them washed. He was not a frequent bather. He followed crowds and noises – spending late nights in the cheapest of bars, where he paid for his drinks by playing the piano and singing bawdy songs collected over fifty years. He dreaded being alone more than anything. When he was alone he could hear the Witch’s Song. It seemed to come out of the black depths of space. It no longer bothered to sound like the all too human rendition that Stefan Gyori had croaked out beside the Black Stone. It no longer even had words. It had become pure tones, almost mathematical in its perfection. With the tones came the pictures—the pictures that told the hidden history of the human race. He knew that that fully understanding the implications of this would bring him to madness—thankfully crowds, beer and bawdy songs were strong bulwarks against thinking too much.

Humans did not come from Earth. They were not the beautiful creatures of symmetry and thoughtful perfection of a loving creator. They were brought from another world where they were creatures of strange form, ruled by strange lusts and stranger religions. They were brought here and mated with hairy simians. They were made to forget their true, yet terrible natures. Some sort of being fed off a spiritual product the humans made and those unconscious of their true form produced more of this substance, more of this drug,- than humans who knew the truth. The Others, they needed the drug. Horrible things that humans’ once called gods in foul places like Xuthltan, then became known as demons when humans began making gods in their own images. Eventually they were forgotten, banished from memory, but oddly grew much stronger as a force in human history. Although forgotten, The Elder Gods continued to grow each year; soon the planet would be theirs. When Dr. Mueller bothered to read the paper and watch the worsening world situation, he saw Their hand at the human throat.

But the song was not about Them. It was about restocking the home world. Some great sorcerer of Ool Athag had written the song to lead human souls back to the world of beast gods who dwelt in pits, where children born with three hands and five eyes were considered lucky, where copulating with demons was a sport. The song affected a magnetic center in the human psyche. It filled the mind with more and more pictures of Ool Athag – of the horrible religious rituals, the strange orgies of sex and blood, the incomprehensible and insane art forms. The soul began to detach itself from the earth. It would be drawn back to the human home world – a strange and surreal Hell that perhaps a Dore or a Sidney Sime could draw, or a mad poet like Justin Geoffrey could sing of. Mueller knew his soul no longer belonged to him – had in effect never belonged to him. He knew it belonged to some monstrous being on the world of purple skies. He knew his soul would fly there after death. And he knew what was “human” in him would die in strange screams and stranger prayers.

It was winter and a fine snow had fallen on the city – a terrible gray snow fouled by factory smoke. Christmas would soon be here, but the religions of men offered him no hope – no amount of nostalgia could overtake the growing dread that filled his being. He passed a beggar in the street. The unshaven man in the thinnest of coats claimed his landlord was about to throw his family out. Could anyone spare a few marks to make sure his family could have a roof over their heads for Christmas?

Suddenly like Scrooge in Dickens’ tale – Mueller became a new man. He pressed a five mark note in the beggar’s astonished hand.

Landlord! Why hadn’t he thought of it before? A landlord doesn’t care from whom his money comes, only that it comes. If he could pay off the dark lords of Ool Athag with a handful of souls—they might release his. Blessed sleep and ignorance could be his again. He could teach the song to dozens of

men—he still had people who remembered him as a great musicologist. He might look like a drunk, might wander the streets of Berlin – but via post he could seem impressive. He would organize a concert – a tribute to Hungarian folk music. The last tune would be the Witches Song. He would send the world of Ool Athag the souls of a few musicians; surely if he dammed enough he could be set free.

It took a few months for backers to agree to fund the concert. It was January of 1914 and all the papers speculated about was the possibility of war. Would the central powers hold together? What did the unrest in Russia mean? Would the reforms in the Ottoman Empire be strong enough to keep the Empire intact? Concerts were not priorities for most Europeans. Mueller’s hope to escape his return to the dark world of Ool Athag had finally awakened a long latent Catholicism. He found frequent and long visits to the Church to be equally as distracting as bars and public houses. Praying long, hard, and loudly could keep the alien song at bay – and transcribing the tune into notes also relived the dark and fearful pressure.

Morality too made a weak return to his life. Surely he could not damn the souls of the musicians? Although most musicians no doubt lead lives that made hell a likely destination – they had hope of reform. Then Thomas Mueller hit on an elegant solution. There were many Jewish musicians in Germany. He would hire only Jews, whose souls were already forfeit, for his concert.

The concert took place on July 4, 1914. He advertised sparingly. He wanted as small an audience as possible. The drafty ill lit theater was in one of Berlin’s poorer neighborhoods. The first part of the show was lively—it drew great applause from the audience, mainly ex-pat Hungarians. The second part was short. When the Witches Song played—some left, two or three fainted in the audience, and an old cellist died during the concert. Mueller paid all of the musicians double, suggested they burn their sheet music and closed the show. As he walked into the night he felt empty. Clean. Free. A big smile appeared on his face. He had done it. He had bought his freedom.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology