- Home

- Mark Lawrence

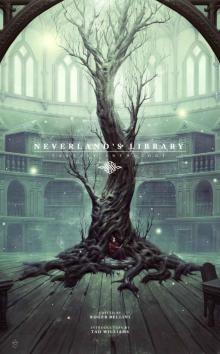

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Page 28

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology Read online

Page 28

“He does that. Remember when he made me dig up all of those bushes when I was ten? It is like a test. Do it right and you’re a grownup.”

“It’s hard, it’s no fun, and I’m only doing it because I have to,” he said through a mouthful of meat and dough. “What’s that supposed to teach me about being a grownup?”

Layla smirked. “That about covers it I think.” She slapped him on the back. “You always were the fast learner.”

“Does that mean I can stop?”

“Nope. Being a grownup is for good.” She grabbed a pocket of her own. “Besides, what else are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. Anything. Think about stuff. Let my mind wander.”

“You know what Dad says about that sort of thing.” She adopted a gruff voice and an educational tone. “Things that wander tend to get lost.”

“Don’t you ever wonder about things?”

“Like what?”

“Well…like why do they call this place Oddspire Fields?”

“That’s easy. Because of the spire,” she said, pointing.

Just beyond the fence at the edge of their land, about a dozen yards away from the stump, was a spire. It was ancient and worn by the elements, but one could still see the intricate designs that had been carved into its surface. It was about twice as tall as Layla and jutted out of the ground at an odd angle. “It’s a spire, it’s in the fields, and that’s odd. Oddspire Fields.”

“But how did it get there? The closest place with spires like that is New Kenvard, and that’s miles away.”

Layla treated the question with her usual level of diligence. She gave it half a thought, then shrugged and took a guess. “I suppose people liked it better that way. Anyway, eat up. Plenty more digging before this thing is out.”

William nodded. The two finished their meal and each went back to work. For a while he continued to think about the spire. New Kenvard was a long way away. If someone had really taken the spire from one of the roofs of the old buildings and installed it here, he couldn’t imagine why, and they’d done a poor job of it besides. It was standing at an odd angle and didn’t have so much as a path leading to it. When he was done turning that mystery over in his head, he started to wonder why no one else had been curious enough to find out the answer. It seemed like no one really cared how things were, or about the mysteries of the world. Not anymore, anyway. Now they just cared about their own little corner of the world and how to get by. As the day rolled on, his thoughts were eventually reduced to variations of “This tree sure has a lot of roots,” and “I wonder how much more I’ll have to dig.”

The last answer, he learned several days later, was plenty. The tree may have been dead, but in its day it must have been mighty, because the roots seemed to go on forever. William hacked through the ones he could, but the main taproot was as thick as his arm and as tough as nails. Day after day he dug deeper, trying to find a point where the root was thin enough to chop through. In the evening of the seventh day, when the hole beside the stump was now well over his head, his shovel struck something strange nestled among the roots.

It wasn’t a stone or a particularly stubborn root. He’d struck enough of them to be a veritable expert. Leaning his shovel against the wall of the pit he’d dug, he got down on his knees and clawed at the object with his hands. It was extremely entangled, whatever it was, but the roots around it were thinner and more brittle than he’d encountered thus far. With a bit more digging, he managed to unearth what turned out to be a small metal box. It was only about two square-feet around and a few inches thick, but it was unlike anything he’d seen before. Rather than being rusted beyond recognition, the box was barely corroded. It was a dark gray color, and when he hauled it out into the fading sun he could just make out some thin engravings forming a complex pattern. One side had a delicate hinge, and the other had two latches. From the looks of it the roots had managed to work their way inside, snapping one of the latches and providing a glimpse within. He twisted and turned the box in the dim light, trying to catch a peek of what it held, but before he could see anything useful, he heard his mother’s voice calling him home for dinner. He tucked the box under his arm and climbed out of the hole, scurrying toward the house.

Their home was a simple one, consisting mostly of one large room. The fireplace, which currently had a heavy iron pot hanging in it, filling the home with the smell of boiling cabbage, nested along the wall opposite the entrance. The room had a table and a few chairs, and the family used it for almost everything but sleeping. For that, there was a pair of bedrooms, one for the children and one for the parents. Outside the house, the family was lucky enough to have its own well and a barn a bit further away.

William ran to their barn to stow the shovel. With the tool in its place, he made ready to bring the box to his father, but something stopped him.

Like most people these days, William’s father had little use for a mystery. He tended to dismiss things he didn’t understand as unnecessary distractions from planting or harvesting. If William showed this box to his father, he would simply tell William to throw it away, or perhaps take it so that he could see about selling it at the market. Granted, William reasoned that selling the box was probably the best idea…but not before he’d had a chance to take a closer look. He lowered it carefully to the ground beneath the feed trough, brushed some hay over it, and hurried to the house. He tried to take a seat as his mother dished out the cabbage soup she’d prepared.

“Uh-uh-uh. You know better than that. You’re filthy. I don’t want you eating with a filthy face and filthy hands. The bucket’s by the door like it always is,” she scolded.

William grumbled and pushed open the door. A heavy wooden pail filled with clean water from the well hung on a hook outside. He splashed enough on his hands and face to get rid of the bulk of the accumulated soil from the day’s digging, then hurried back. When he shut the door behind him, his father and sister were taking their seats. His mother put a hearty bowl before each member of the family before she sat as well. William hungrily dug into it. A full day of shoveling was enough to make any meal a banquet.

“There, you see. A good appetite is a sign you’ve been putting in a good day’s work. You’ve made a lot of progress, William, I’m proud of you. Another few days and we’ll be able to hitch the oxen to that stump and pull it out.”

William simply nodded and industriously went to work emptying his bowl, as though doing so quickly enough would win him a prize. When the meal was through, he made a show of stretching and yawning.

“I’m really tired, Father,” he said. “I’m going to go to bed early, all right?”

“Of course,” his father replied. “Get a good night’s sleep. Maybe if you get an early start on it tomorrow, you can have the job done by nightfall.” He watched with a smile as his son carried his bowl to the washbasin, then gathered his nightclothes and went to his room. “You see, Clara? I knew giving him an important job would turn him around,” he said proudly.

“He just needed some time, Tom,” said William’s mother. “And you just needed to have faith in him.”

“Isn’t it good to see your brother finally showing some interest in the land, sweetie?” he asked Layla.

The girl pursed her lips and looked to the bedroom door. “He’s interested all right,” she remarked with a raised eyebrow. “Dad, I’m a little tired too. I think I’ll turn in.”

“Good night, then. Maybe if the two of you are up early enough and finish your work, we can take a trip to New Kenvard.”

“Sounds great, Dad,” Layla said, standing up to kiss him on the forehead. “Good night.”

He watched as she got herself ready and slipped into the bedroom as well, then smiled to his wife. “We’re raising a great couple of farmers, Clara.”

“I’ve always thought so, dear,” she said.

#

William struggled to stay awake in his darkened bedroom. He hadn’t been lying when he said he

was tired. A week of digging from sunrise to sunset would be enough to make anyone exhausted and sore, but he forced himself to stay awake until heard his parents retire for the night. Once their door was shut, he crawled out of bed as quietly as possible and eased open the shutters to his window. They swung open with the whisper of a scrape. He held his breath and looked toward his sister. In the light of the moon, he saw her still motionless in bed. He released a sigh of relief, then pulled himself to the sill and promptly tumbled to the ground.

He sat up and shook his head, then winced and waited for his parents to swing their window open and order him back to his room, or his sister to poke her head out and demand to know what he was up to. A few moments passed with nothing, but he should have expected as much. They all worked as hard as he did. It would take more than a ten-year-old plopping down on the grass to wake them. He brushed himself off and ran barefoot to the barn. For many people, the air would have been a bit too brisk to be running around in one’s pajamas, but Oddspire Fields was a part of the northern kingdoms. Locals like him tended not to bother with a coat until it was below freezing.

William grunted against the barn door and tugged it open. The unmistakable fragrance of large animals wafted out from inside, but there was little moonlight and few windows, so the interior of the barn was pitch black.

“Darn,” he muttered. “I should have brought a—”

“Looking for this?”

The voice came out of nowhere, startling William. His panicked brain told him to run, but without selecting a useful destination first, he only made it three steps before colliding with the barn door and falling to the ground. Dazed, he blinked until the smirking face of his sister came into view. She was holding an unlit lantern in one hand and had the other outstretched to help him to his feet.

“You know, for such a bright kid, you’re lousy at running away from home,” Layla said, pulling him up.

“I wasn’t running away from home,” he defended, brushing himself off.

“Then what are you doing out here?” She set the lantern down and sparked it to flame.

“Nothing!”

“Just felt like visiting the cows? Come on, Willy. What’ve you got?”

He crossed his arms and huffed. “Fine, I’ll show you. But you can’t tell Mother and Father until I say, since I found it.”

“That depends on if it’s juicy enough to be worth getting me out of bed,” she said, ruffling his hair.

The pair slipped into the barn. William’s father was primarily a farmer, but to work the land properly he kept a pair of oxen for plowing and hauling. The family also had a horse and cart for taking the harvest to the market and the family to town when the need arose. Add to that their two cows, the coop of chickens beside the barn, and a few sheep they’d picked up the previous season and Layla had her hands full keeping the animals fed and healthy. She raised the lantern.

“Easy everyone. We’re just visiting,” she cooed to the livestock when their arrival caused the inevitable stir. The animals had all gathered themselves at the far side of the barn for some reason, and her words did little to calm them. “Never seen them do that before,” she mused. “I wonder what’s gotten into them.”

“Over here,” William said, digging into the hay beneath the trough. “Bring the light. And close the door.”

Layla pushed the door shut and crouched down beside her brother as he revealed the treasure he’d unearthed earlier that day. Somehow it looked even more mysterious in the light of the lantern. The flickering flame caused shadows to dance across the designs on the surface, deepening the appearance of the etched lines. Twisting the box made shimmers run along the shapes and sigils, almost seeming to make them pulse with light.

“Ooo,” Layla remarked. “That’s a fancy box. Where’d you find it?”

“It was buried under that tree! What do you think is inside?”

She shrugged. “Well it’s half-open, so probably dirt and bugs now.”

“Well yeah, but what else? I’m going to try to get it the rest of the way open.” He took two of the trowels from their place on the barn wall and wedged them inside the opening the roots had made. He eagerly tugged and twisted them.

“Look at you getting so excited. How come I never see you get so giddy on the farm?”

“Because nothing interesting ever happens on the farm,” he grunted, fighting with the remarkably sturdy little box. “When was the last time anything on the farm was half as amazing as—” He gave one more yank. “—this!”

The box popped open and both siblings leaned close, excited to see their discovery. As expected, a fair amount of soil had found its way inside, along with some withered and blackened bits of root, some dead beetles, and some shriveled worms. He brushed them away with a grimace until he’d cleared off a bundle of grimy fabric. The cloth was strange. It was finely woven, so much so that it was almost as smooth as silk. The surface glittered slightly in the light, even through the layer of dirt. The bundle was almost the same shape as the box, a rough rectangle with an irregular bulge, and there was a black ribbon securing it shut. He tugged at the ends like a child opening a long-awaited present and unwrapped the cloth. Layla’s eyes widened with anticipation…then her shoulders sagged when she saw the contents.

“Congratulations, Willy. You found a book and a stick,” she said flatly.

He didn’t reply. Unlike her, the sight of the book didn’t wipe away his enthusiasm; it set it aflame. He picked up the tome, a thin volume with a strange purple-black leather cover and bound with sinewy twine.

“It’s a book, Layla. A book! I’ve never seen one this close before.”

“Well sure, Willy, but what good is it going to do us? I can’t read and neither can you. I don’t even think Mom and Dad can. The stick is kind of pretty though.”

She reached down and picked it up, turning it in the light of the lantern. It was some sort of silvery wood, as thick as her finger and perhaps a foot long. Like the box, it was covered with fine engravings, but these were far more intricate. It tapered slightly from one end to the other and was perfectly straight. Both ends were rounded.

“I know I can’t read, but with a book, maybe I could learn,” he said. He flipped through the pages. They were covered with shapes far more complex and varied than he’d ever seen written anywhere else…not that he’d seen very much writing.

“Dad will teach you everything you want to know about running a farm. What do you need to learn to read for?”

“To learn everything else,” he said. “Hold the lantern closer.”

Layla looked to the dwindling flame.

“I guess it was low on oil. Come on. Maybe the moon will be enough.”

He gathered the book and hid the cloth and the box while she snuffed out the lantern flame. The moon was low on the horizon. To get the best light, they made their way to the far side of the barn. While William pored hungrily over the pages, Layla continued to inspect the carved wood.

“How do you figure they got the carvings so fine?” she asked. “They’re so intricate, I can’t even make out the smallest ones.”

“I don’t know. Mom said they make fine jewelry in South Crescent. Maybe that’s where it’s from.”

“That’s silly. Why would someone come all the way from across the sea with a carved stick, then bury it in a field?”

“I thought you said I was the one who asked too many questions.”

She shrugged. “It isn’t the first time I’ve picked up a bad habit. Oh, darn it!”

“What is it?”

“There’s a mole. Get out of here, you little pest,” she said, waggling the stick angrily. “If you ruin even one stalk of wheat I’ll—”

There was a sharp crackle and a brilliant flash of violet light. William looked up from the book in time to see a glimmering bolt of black and purple lance through the air and strike the ground, narrowly missing the scurrying mole, and blackening the earth where it had been.

La

yla stood perfectly still, eyes as wide as saucers. The artifact was still in her hand, held in precisely the same position. After a few stunned seconds she held it out at arm’s length, then dropped it to the ground.

“What did you do?” William yelped.

“I don’t know! I thought about how I wanted to get rid of the little monster and then, zap!”

The siblings looked at the stick. Its tip still glowed faintly, and the engravings had an undeniable shimmer to them now.

“It’s a…it’s a magic wand. Willy, you found a magic wand!”

For a moment they both kept a cautious distance. Then at the same instant, they dove for it.

“Give it to me! I found it! You already had a turn!” William whined.

“Oh no, Willy,” she said, planting a hand on his forehead to hold him at bay. “You picked the book, you stick with the book.” She snagged the wand. “Go get our boots. We’ll go out in the field. I want to see what sort of tricks this thing can do.”

#

After a clumsy fumble through the darkened house that made it clear his parents were harder to disturb than he’d ever imagined, William returned, and they went on their way toward the stump. Layla reasoned that since William was already digging there, anything that needed covering up could get a few scoops of loose soil over it, and no one would be the wiser. Considering how little interest she seemed to have in learning, Layla could be fiendishly clever when it came to getting away with things. As they walked, though, William became increasingly uneasy.

“I don’t know, Layla,” he said, face uneasy. “The more I think about it, the more I feel like this is a bad idea.”

“That’s why thinking is bad sometimes, Willy. Dad says if you want to start doing something, the best way to start doing it is to start doing it.”

William considered the words for a moment. “Sometimes Father’s sayings don’t make much sense.”

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology