- Home

- Mark Lawrence

King of Thorns be-2 Page 21

King of Thorns be-2 Read online

Page 21

We stayed five days in Alaric Maladon’s hall. Not in the guest hall but in his great hall. They put a chair for me on the dais, nearly as grand as the Duke’s own, and I sat there wrapped in furs when I shivered and stripped to the waist when I sweated. Makin and the Brothers celebrated with Maladon’s people. Women appeared for the first time in any number, carrying the ale in flagons and horns from the storehouse, knives at their hips, eating at the long tables like the men, drinking and laughing almost as loud. One, near as tall as me, blond as milk and handsome in a raw-boned way, came up to my chair as I huddled in my furs. “My thanks, King Jorg,” she said.

“I could be making it all up,” I said. Feeling rotten and ugly made me want to sour the day.

She grinned. “The ground hasn’t shaken since they brought you back. The sky is clear.”

“What’s that?” I asked. She had a clay pot in one hand, filled with black and glistening paste, a twist of hide next to it.

“Ekatri gave it to me. A salve for the burns, and a powder to swallow in water to fight the poison in your blood.”

I managed half a laugh before the pain stopped me. “The old witch who keeps predicting my failures? There’ll be poison in me if I take anything she sends all right. It’s probably how the future turns out the way she says it will.”

The woman-girl maybe-laughed. “That’s not how volvas are. Besides, my father would take it in poor humour if you died here. It would reflect badly upon him, and Ekatri depends upon his favour.”

“Your father?” I asked.

“Duke Maladon, silly,” she said and walked away leaving the pot and wrap in my lap. I watched her backside as she went. I thought perhaps I wouldn’t die if I could still find time to watch a well-crafted bottom.

She looked over her shoulder and caught me watching. “I’m Elin.” And she walked on, lost in the crowd and the smoke.

I took Ekatri’s powder and bit on a leather strap as Makin dabbed the ointment on my burns. He may have a light touch with a sword but as a healer he seemed to have ten thumbs. I nearly chewed through the strap but when he’d finished the pain had died to a dull roar.

The girl, Elin, said the volva depended upon her father’s favour. I hoped that was so, rather than he on hers. Makin had been digging around, asking my questions in the right corners, doing that thing he does, the one that gets him answers. No one had said it, but if you stacked those answers up and looked at the pile from the right angle, it seemed the ice-witch, Skilfar, had a cold finger in every northern pie. I didn’t doubt that many a jarl and north-lord danced to her tune without ever knowing it. Ekatri though, Makin said she was a smaller fish. I wondered on that one, sitting alone with my pain in the quiet of night. Alaric of Maladon should mind himself I thought-even the smallest fish can choke you.

I sat for five days, feeding on oat-mush whilst the Brothers gorged on roasted pig, ox heads, fat trout from the lake, sugar apples, and anything else that would be agony for me to chew. Each night more of the Duke’s kith and kin arrived to swell the throng. Neighbours too. Men of the Hagenfast, beards plaited with locks from those who died under their axes, true Vikings tall and fair and cruel, out of Iron Fort and ports north, and a lone fat warrior from the marches of Snjar Songr, sour with seal grease and not parting with any of the furs that bundled him despite the hall’s heat.

I watched Rike win the wrestling contest after ten drunken heats, finally throwing down a Viking with slab-muscled arms and a permanently florid face. I watched Red Kent come first in the throwing of the hand-axe at a wooden target board, and third in the log-splitting. A tall local with pale eyes beat Grumlow into second in the business of knife-throwing, but Grumlow was ever a stabber and better motivated to hit a target if it breathed. They told me Row acquitted himself well in the archery, but that took place outside and I didn’t let them move me. Makin lost at everything, but then again Makin knows that winners may be admired but they are not liked.

The Duke and Sindri sat beside me often enough, asking for the tale of Ferrakind’s end, but I shook my head and told it with a single word. “Wet.”

The ale flowed, but I drank only water and watched the torch-flames more often than I watched the Danes at their feasting and sport. Flames held new colours for me. I thought of Gog, destroyed by fire, and of his little brother who bore the name I gave him, Magog, for only a few hours. I thought of Gorgoth among the silence of the trolls in the black caverns. I held the copper box in my hand and wondered if its contents would distract me from my pain.

Most of all, though, as boys do when they’re hurt-and at fourteen I discovered I was still a boy if the hurt came fierce enough-I thought of my mother. I remembered how I twisted and moaned on the slopes after Sindri left me, the agony that held me and the thirst I had, nearly as large as the pain. I would have fitted well amongst the dying at Mabberton, amongst the wounded that I had watched with a smile, coiled about their hurts, calling for water. And when pain bites, men bargain. Boys too. We twist and turn, we plead and beg, we offer our tormentor what he wants so that the hurting will stop. And when there is no torturer to placate, no hooded man with hot irons and tongs, just a burn you can’t escape, we bargain with God, or ourselves, depending on the size of our egos. I made mock of the dying at Mabberton and now their ghosts watched me burn. Take the pain, I said, and I will be a good man. Or if not that, a better man. We all become weasels with enough hurt on us. But I think a small part of it was more than that. A small part was that terrible two-edged sword called experience, cutting away at the cruel child I was, carving out whatever man might be yet to come. I promised a better one. Though I have been known to lie.

We were bound for Wennith on the Horse Coast that day, when Mabberton burned. Wennith, where my grandfather sits upon his throne in a high castle overlooking the sea. Or so my mother told me, for I had never seen it. Corion came from the Horse Coast. Perhaps he had aimed me there, a weapon to settle some old score for him. In any event, in Duke Maladon’s hall in the quiet hours before dawn when the torches failed and the lamps guttered out, amid snoring Norsemen slumped over their tables, my thoughts turned once more to Wennith. I had friends in the north now, but to win this Hundred War of ours, of mine, I might need some family support.

Lawrence, Mark

King of Thorns

Age set its hand on Brother Row and left him forever fifty, not wanting to touch him a second time. Grey, grizzled, lean, gristly, mean. That pale-eyed old man will bend and twist but never break. He’ll hold where the better man would fail beneath his load. The shortest of our number, rank and filthy, seamed with forgotten scars, often overlooked by men who had scant time to reflect on their mistake.

29

Four years earlier

On the long journey south I questioned the motivation for my diversion more than once. More than a hundred times, truth be told. The fact of the matter was that I hadn’t found what I needed yet. I didn’t know what I needed, but I knew it wasn’t in the Haunt. My old tutor, Lundist, once said that if you don’t know where to look for something, just start looking where you are. For a clever man he could be very stupid. I planned to look everywhere.

We rode out on the sixth day. I sat in Brath’s saddle stiff in every muscle, my face aching and weeping.

“You’re still sick,” Makin said beside me.

“I’m sicker of sitting in that chair watching you gorge yourself as if your only ambition were to be spherical,” I said.

The Duke came to the doors of his hall with a hundred and more of his warriors to see us off. Sindri stood at his right hand, Elin at his left. Alaric led them in a cheer. Three times they roared and shook their axes overhead. They were a scary enough bunch saying farewell to friends. I didn’t fancy the chances of any they deemed to be enemies.

The Duke left his men to come to my side. “You worked a magic here, Jorg. It will not be forgotten.”

I nodded. “Leave the Heimrift in peace, Duke,” I said. “Halradra and his sons are sleeping. No need t

o go poking them.”

“And you have a friend up there.” He smiled.

“He’s no friend of mine,” I said. Part of me wished he was though. I liked Gorgoth. Unfortunately he was a good judge of men.

“Good travels.” Sindri came to stand beside his father, grinning as ever.

“Come back to us in the winter, King Jorg.” Elin joined them.

“You wouldn’t want to see this ugly face again.” I watched her pale eyes.

“A man’s scars tell his story. Yours is a story I like to read,” she said.

I had to grin at that, though it hurt me. “Ha!” And I wheeled Brath to lead my Brothers south.

Back on the road, and with regular applications of Ekatri’s black ointment, my face began to heal, the raw flesh congealing to an ugly mass of scar tissue. From the right you got handsome Jorgy Ancrath, from the left, something monstrous: my true nature showing through, some might say. The pain eased, replaced by an unpleasant tightness and a deeper burning around the bones. At last I could bear to eat. Now all the fine servings from the Duke’s table were trailing farther and farther behind us, I discovered that I had an awful hunger about me. And that’s a thing about the road. Out on a horse, trotting the ways of empire day after day with nothing to eat but what you can carry or steal, you discover that everything tastes good when your stomach is empty. If you look at a mouldy piece of cheese and your mouth doesn’t water-you’re just not proper hungry.

In the Haunt the cooks would honey-glaze venison and garnish it with baked, rosemary-sprinkled dormice just to tempt my palate. After days in the saddle I find that in order for food to tempt me it must be either hot or cold and preferably, though not essentially, if it is animal, that it should not be moving and should once have possessed a backbone.

Around the fire at camp on that first evening we made a subdued huddle, somehow more reduced by the absence of our smallest companion than by that of our largest. I stared at the flames and imagined a sympathetic tingling in the bones of my jaw, even under the deadening effect of the ointment.

“I miss the little fellow.” Grumlow surprised me.

“Aye.” Sim spat.

Red Kent looked up from the polishing of his axe. “Did he give good account of himself, Jorg?”

“He saved me and Gorgoth both,” I said. “And he finished the fire-mage before he died.”

“Sounds about right,” Row said. “He were a godless bastard, that one, but he had a fire in him, God did he.”

“Makin,” I said.

He looked up, the flames reflected in his eyes.

“Since Coddin is at home…” I paused then, realizing that I’d called the Haunt “home” for the first time. “Since Coddin is at home, and the Nuban isn’t with us…”

“Yes?” he said.

“I’m saying, if I set on a path that’s…maybe a little too harsh. Just let me know. All right?”

He pursed those too-fleshy lips of his then sucked air in through his teeth. “I’ll try,” he said. He’d been trying all these years, I knew that, but now I gave him permission.

For a week we skirted villages, circled towns, and picked our way through the soft edges of the kingdoms we had passed on our journey north. We came to the settlement of Rye, too big to be a village, too recent and too random to be a town. On our trip out we had purchased provisions there and with our saddlebags flapping empty we rode in to resupply. Paying for goods still feels odd to me, but it’s a good habit to get into when you’ve the coin to spare. Of course you should steal every now and then, take something by force just for the wickedness of it, or how else will you keep your hand in the game? But aside from that, paying is recommended, especially if you’re a king with a pocketful of gold.

The main square in Rye isn’t square and it’s only just about “main” as there are other markets and clearings in Rye almost as large. Rike had loaded the last sack of oats onto that great carthorse of his and Makin was trying to strap his saddlebag over four gutted hares in their fur when the crowd flowing around us seemed to part like the Red Sea for an old man. I had been leaning against Brath feeling rather faint. Summer had decided to give us a preview and the sun came beating down out of a faded sky. My face ached like a bastard and a fever had got its claws into me.

“Prince of Thorns!” the old fellow cried as he homed in on me, loud enough to turn heads.

“That’d be ‘king’ if it’s anything,” I muttered. “And if there’s a Thorns on the map then I must have missed it.”

He stopped about a yard in front of me, and drew himself up tall. A skinny fellow, dried like a prune, with white hair fluffing at the sides of a bald head. His eyes were milky, though not like cataracts but somehow pearly with a hint of rainbows. “Prince of Thorns!” Louder this time. People started to close in.

“Go away.” I used my quiet voice, the one that recommends you listen.

“The Gilden Gate will open for the Prince of Arrow.” Something electric crackled in the air around us, the white fluff stood out from the sides of his head. “You can only-”

There’s an art to the quick drawing of a sword. Providing the scabbard strap is undone, and I always keep mine so, you can propel the whole blade several feet into the air just by hooking a hand loosely under one side of the cross-guard and literally throwing it upward. With good timing and a quick turn of the body you can snatch the hilt at the apex of the throw and as the sword falls you can turn that momentum into a sudden thrust into whatever is beside you.

I looked back over my shoulder. The man’s eyes still had their milky sheen but he’d stopped prophesying on me. By stepping away I drew the blade from his chest. He looked down at the scarlet wound but, oddly, did not fall.

I waited a moment, then another. The crowd kept their silence and the old man kept standing, making a close study of the blood pumping down his stomach.

“Hey,” I said.

He looked up at that, which helped. His chin had been in the way. I took his head with one clean blow. I’m not one to boast but it’s not easy to decapitate a man in one swing. I’ve seen expert axemen take three blows to do it at an execution when their victim’s neck is laid out for them on a block.

The seer had enough grace to let his body topple after his head landed by his feet. He kept looking at me though, with those pearly eyes. There’s no magic in it, a severed head can watch you for close on a minute if you let it, but they say it’s bad luck to be the last thing it sees.

I picked the head up by its tufts of hair and held it facing me at eye level. “Seriously? You can tell me what I am and am not going to sit on in years to come and you didn’t see that one coming?” I kept my voice loud for the crowd. “This fake has been living off your misery and the misery of folk like you for years.”

And in a quiet voice, just for the seer and any who watched me through his eyes, for all those who watched this moment across the span of years before I was born. “I will make my own future. Being dead doesn’t make you right. Everybody dies.”

The lips smiled. They writhed. “Dead King,” they said, without sound, and where I touched him my skin crawled, as if a spider unfolded itself in my palm.

I dropped the head and kicked it into the crowd. I say “kicked” but in truth it’s a bad idea to kick a head. I learned that years ago, a lesson that cost me two broken toes. What you want to do is shove the head with the side of your foot, like you’re throwing it. It’s going to roll anyhow so you don’t need that much force. See, the thing about severed heads is the owner no longer has any interest in minimizing the force of the blow, or any ability to do so for that matter. When you kick somebody in the head as you do from time to time, they tend to be actively trying to move themselves out of the way and the contact is lessened. A severed head is a dead weight, even if it’s watching you.

And that exhausts my insights into the kicking of severed heads. Admittedly it’s more than most people have to offer on the subject but there were Mayans who knew a lot m

ore than I do. That of course is a whole different ball-game.

Makin finished with his straps and stepped beside me. “That was probably too harsh,” he said. “You did ask me to point these things out.”

“Fuck off,” I said.

I waved to the Brothers. “Let’s ride.”

For close on a hundred miles we retraced our path along the North Way, down through the duchies of Parquat and Bavar where most travellers are welcome so long as they don’t plan to stay, and even our sort are tolerated so long as we don’t get off our horses.

The town of Hanver greeted us with bunting. Among those peaceful huddles of thatched cottages that I had remarked upon whilst travelling north, Hanver lay equally untouched and unspoiled, a place not visited by war and cradled amidst idyllic farmland divided into tiny fertile fields.

“Looks like a holy day.” Kent stood in his stirrups to see. For all that he was a dark and deadly bastard, Kent had himself a pious nature, the good kind of pious, or at least the better kind.

“Gah.” Rike liked his celebrations louder, more wild, and more likely to end in a riot.

“There’ll be chorals,” Sim said, ever the music-lover.

And so without much more than a nod toward the fact I was king of Renar and that none of them were much more than scabby peasants at the end of it all, the Brothers led me into Hanver. We rode in down the main street, through the crowd, the locals with scrubbed faces, sporting their best rags, the children waving ribbon-sticks, some clutching sugar-apples kept sweet over winter. The Brothers set off on separate ways, Sim to the church, Grumlow to the smithy, Rike handing his reins to a boy outside the first tavern. Row, more particular, chose the second tavern and Kent veered off to a stables to get an expert eye on Hellax’s front right foreleg.

“Looks like there’ll be more than chorals.” Makin nodded ahead to the main square. A wooden platform had been erected, fresh timbers, still weeping. A wide stage, a gallows frame, and three strangling cords dangling in the breeze.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

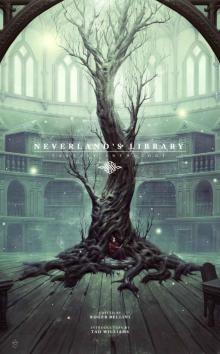

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology