- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Page 16

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Read online

Page 16

I could have stayed to help her recover. Perhaps I should have. But I never claimed to be a hero or even to be brave, and I knew that if I held her whole again in my arms, I would lack the courage to do what needed to be done. Also, if I tried, Mia would demand to come with me.

So I sat for a week holding her hand, and then I got ready to go. I stood and I kissed her cheek. I thought my goodbye rather than spoke it, because I’m a Hayes, dammit, and we don’t say stuff like that even when the other party is unconscious. I told her that when some hearts break the world breaks with them, and although mine had broken the day that her accident finally caught up with her, I wasn’t going to let the world suffer, too. I would go back as Demus and close the circle. And by doing so the data on the memory stick would be her memory, free of paradox, and she would be well again.

I kissed her forehead. Love had come into my world unexpected, unannounced, like a gentle breeze, hardly noticed at first, yet where it wandered it moved everything. Now there was no end to where I would let it carry me.

I straightened up and watched her for a moment, seemingly sleeping. I left with a sigh so deep that it hurt something inside me that I would like to imagine was more metaphysical than just my slowly healing ribs. I left knowing that I wasn’t ever coming back.

The data coming in from the researchers I still had out in the field had narrowed down the source of the intermittent barrier to Birmingham. Which meant that, barring the unlikely event of a mad scientist experimenting in his mother’s basement, all I had to do to find those responsible for it was to call in at the University of Birmingham’s physics department and make some discreet enquiries.

I walked from Mia’s hospital to my car, put the satnav on and drove to Birmingham. Bizarrely, now that my fate was sealed, a weight seemed to have lifted from me. Perhaps it was the burden of having to fight the inevitable. Maybe I just needed to be doing something, making progress, rather than sitting helpless at Mia’s bedside, just waiting.

I didn’t know whether months from now, when her brain was ready to accept the reimplanted memories, it would work. The technology was still new, and nobody had ever had so long a period of their life restored to them. So, I didn’t know whether it would be successful. But I damn well knew that if it wasn’t then it would not be my fault for lack of trying. If Mia could remember again, then she would remember why I had abandoned her. She would know that I’d given time its due and gone back to play the part written out for me when I was still a child.

I drove through the afternoon, hardly noticing the towns pass by. I remember Kettering, Coventry, and suddenly the urban sprawl of Birmingham. The university, contrary to expectation based on the city’s grimy industrial heritage, sits in green acres, and while it may be a far remove from the dreaming Gothic spires of Cambridge, the red-brick buildings, most of them scattered among the fields and woods of the campus in the 1960s, are pleasant enough to look at.

I drove smartly up to the School of Physics and Astronomy and asked for the first of the staff members whose name showed in my list of those having applied to the Institute of Temporal Studies for a research grant in the last eighteen months.

Dr Root appeared in the foyer minutes later, somewhat breathless and straightening his jacket. At first I thought he was a schoolboy stuffed into an interview suit. Very young, painfully thin, a quick, nervous way about him, long-fingered hands always busy. He appeared somewhat star-struck. ‘Professor Hayes!’

‘Dr Root.’ I shook his hand. ‘Call me Nick.’

‘I . . . uh. I didn’t know we were expecting you.’

I understood his confusion. It’s not often that a world-famous Nobel Prize winner who happens to direct a major scientific institute turns up on your doorstep. ‘Sorry. I should have called ahead—’

‘No, no! You’re more than welcome, Professor!’ He looked suddenly horrified, realising he’d interrupted me.

‘Call me Nick.’ I grinned then cut to the chase. ‘Someone here has been running a time-rig for most of the last fortnight. Who would that be?’

Dr Root blinked, looked rather guilty, and then rallied himself. ‘That would be me.’

‘Direct hit, first time.’ I gestured to the doors into the main building. ‘I’d consider it a great favour if you were to show me what you’re up to, Elias. It is Elias, isn’t it?’

‘I . . . uh. Eli,’ he said. ‘But Elias is fine.’

‘Eli it is.’ I took his elbow and steered him towards the doors.

Eli finally took the hint and started to lead me in. He paused by the elevator. ‘The lab’s on the third floor.’

‘Let’s take the stairs.’ I thought it best to keep him moving. He didn’t actually have to show me anything if he didn’t want to. I wasn’t the time police.

‘How . . .’ He turned to look back at me as we climbed the steps. ‘How did you know I was running my experiment? I mean, if you don’t mind me asking.’

I smiled what I hoped was a reassuring smile. ‘Doctor Who. Isn’t that what they call me?’

‘I . . . uh.’ He tripped on the next step and sprawled on to the landing.

I helped him up. ‘You’re throwing out temporal micro-disturbance over ten thousand square miles.’

‘Well, I don’t know . . . Ten thousand?’ He rubbed his knees and looked up at me in shock. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Very.’

‘But that would mean . . .’ The look of horror that stole over his face let me know just how much he understood what he was doing.

‘Fortunately, the affected area is an ellipse,’ I said.

‘So London . . .’

‘Has not been affected.’ I followed him out of the stairwell and along a corridor. He was practically sprinting now. Clearly, he understood that the disturbance his experiment was propagating would interfere with time travel, but he had not anticipated the range of the phenomenon. Right now, he was beginning to realise that if he simply rotated his equipment he would sweep the barrier across the designated travelling sites in London and bring to a stumbling, possibly fatal, halt the journeys of the many hundreds of travellers housed there.

Eli Root unlocked a side room, flicked on the lights, and there before us was a fairly standard time-rig, the towering electromagnets almost hidden from view behind the bulky moderators that had been crowded around them.

‘I never thought it would require so many moderators.’ I’d never actually built a barrier generator before. ‘Have you tried sympathetic generators at the L2 and L5 points?’

Eli blinked at me again and pulled a pair of glasses from his inner pocket. ‘Sympathetic? At . . . But that’s just . . .’ – he frowned and considered it for a moment before the slow dawning of realisation across his face – ‘. . . genius.’

‘Just a suggestion,’ I said.

Eli’s face suddenly fell, as though something precious had been snatched away from him. ‘You’ve discovered this already, haven’t you? But why isn’t it in the literature? I mean . . . How long have you known?’

‘A while.’ I hadn’t the heart to tell him that I’d finalised the necessary proofs as a teenager, almost certainly before he was even born. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll let you tell everyone.’

‘W . . . what do you mean?’

‘I need you to do me a favour, Eli. A big favour. Only unlike most favours, I’m going to pay for it. I’m going to privately match all your public research funding for the next ten years. Sound good?’

Dr Root spluttered a laugh. ‘Do you want both my kidneys or just the one?’

‘I want you to turn this machine off for a week. And after that I want you to turn it back on and keep it running no matter what anyone else says to you.’

‘For how long?’ he asked.

‘Until the government institute their own barrier across the entire country.’

‘I don’t . . . but why would they do that?’

‘To stop people going back.’ I reached into my pocket. ‘I can write you a ch

eque for the first instalment. Let’s call it two hundred and fifty thousand pounds.’

The excitement that suddenly lit Doctor Elias Root up was nothing to do with the quarter of a million. I don’t think that even registered with him. ‘You’ve done it! Haven’t you? You’ve bloody done it!’ He reached for me, then thinking better of it hugged himself fiercely. ‘How? I mean the Hayes Conundrum . . . How could you— How did you solve it? And then even with that, it would take . . .’ He ran long fingers up into his dark locks, tugging at his hair.

‘Focus, Eli.’ I waved my hand in front of his face to get his attention. ‘Money. Lots of lovely money. And really all I’m asking is for you to switch off for a week. I mean, failing that I can pretty much buy the university and switch it off for you.’ I couldn’t, but I wanted to get the message across. What I would do instead would be to pay someone unscrupulous to total the building’s power supply, but I wanted to keep the man’s attention on the money.

‘Couldn’t you just tell me how you did it instead?’ He was almost begging.

I shook my head, trying not to smile. ‘You’ll find out soon enough. The international community really have their teeth into the theory now. Pieces of the puzzle are being assembled all across the world. The dam’s bursting at the seams.’ I slapped his arm. ‘You’re a bright fellow. This barrier business proves it. So why don’t I just leave the rest as an exercise for the student? That way you can still get a piece of the action. Have your name on part of it.’ I paused. ‘Look, what you really need to be thinking about is why your barrier is so efficient. You should look at n-spaces on high-order manifolds of the zeta-mapping. Collaborate with a topologist in your maths department if the equations get away from you. Those guys are all looking for experimentalist partners. Susan Pichencko is here, isn’t she? Go talk to her about it.’

Young Eli looked as if I’d given him the biggest present ever in the history of Christmas. He still didn’t seem to have registered the huge financial bribe I’d shoved in his face.

‘Thank you, Professor Hayes! Thank you so much!’ He continued to tug his hair with one hand while seizing mine for vigorous shaking in the other. ‘My God! The zeta-mapping! I know Susan . . . I just never— I have so much to do!’

‘Nick. Call me Nick, Eli. I’m just some guy at the end of the day. We all are.’

‘Tap.’ He nodded, still distracted. ‘My friends call me Tap. A joke on my surname.’

‘Just remember the bit about turning the rig off for a week, Tap. Starting today. And then back on forever after. Yes?’

‘Yes.’ He nodded.

‘I’ll have my solicitor send you a contract for the funding.’ I escaped from the handshake and started towards the door.

‘You’re leaving?’ He looked bereft.

‘Very much so.’ I opened the door. ‘Tempus fugit!’ And with that I was striding away towards the stairs.

By evening I was approaching the castle through the fields of dozing solar cells. The Tower of Tricks hulked before me, a black fist against the paling sky. I had arranged Elias Root’s funding with my solicitor on the phone as I drove.

For the last time, I raised the portcullises and decelerated beneath their metal-shod teeth into the courtyard beyond. In my office I took from my wall safe the letters I’d made ready for the people I cared about. It’s hard to write anything with that sort of finality. They weren’t quite suicide notes, but they almost were. Where do you start? How do you finish? What will the person be thinking by the time they reach the last word and know that they can never respond? I wrote them in the hope they would somehow release the people reading them. I told my mother that I had always loved her but never found the words to say it. I reminded John of the good times we’d had and asked him to be there for Mia even if she was angry. I told Simon that the adventure never ended – I was merely changing game systems. Mia I told that I would see her again, and that all she had to do was remember. I told her it wasn’t a sacrifice or a gift, it was just who I had always been. I was going back to write those memories and to ensure they were returned to her. Memory is all we are, I said. So don’t forget me.

Events seemed to be accelerating now, time running away from me like sand between my fingers. I knew I could wait until the next day, the next week, if I wanted to, but some convictions have to be acted on. Any delay dilutes the certainty, allows stray thoughts to worm their way into your mind and cloud that clarity with doubt. I didn’t want to die. I didn’t want to go back and fulfil the prophecy I’d lived with all my life: the one Demus delivered into my hands when I was still a boy. He’d taken away one death sentence and replaced it with another, but that second one had offered me twenty-five more years.

‘Twenty-five years.’ I said it out loud as I descended the spiral staircase into the travellers’ cave. ‘Twenty-five years.’ At first they had crawled by so slowly and so sweetly that it felt as though I had been given an eternity. Lately, though, the months had zipped past, blurred by the speed of their passage, like trees seen from a train. And now, with them stacked behind me, with their weight against my shoulders, I felt no more ready to go than I had at fifteen.

Perhaps it would be the same even if I lived to be eighty. Perhaps it’s the same for everyone, no matter how many years they’re trailing behind them. Always the child standing there wearing an old man’s clothes, an old skin hanging from old bones, and wondering where the days went, remembering how marvellous it had been to fritter away so many slow and sunny days. And wanting more.

Demus and Mia were waiting for me, just as they had been all my life. I would go. She would stay. If her time trail persisted until after her recovery, then the barrier would keep her here in the present. The world would have to take its chances with whatever paradox resulted. I wasn’t going to let her try to stop me. My calculations indicated that the time barrier would dilute the effect that had killed Ellery Elmwood. The universe would want to kill Mia for not going back as her time trail demanded, but the barrier would help hide her from that retribution. She should be fine. She would rebuild her life just as the doctors had rebuilt her body. I didn’t know why she would choose to come back after me. To stop me, I guessed. But the fact was that I had an important job to do in 1986, and she did not. And so I would close the door behind me and leave it in place forever to shield her.

The instrumentation in the traveller cave indicated that Dr Root had done what I asked and turned his rig off, stopping the temporal micro-disruptions propagating across the country. All set. Ready to go.

It wasn’t until I approached my time trail that I noticed the tattoo on my hand, the closed integral, black and irrefutable across the skin on my right wrist. I hadn’t even had it for six months yet and already my gaze flowed over it as though it wasn’t there, just part of me, as much a piece of the design as the pattern of my moles. It had been its absence on the wrist of my time trail that drew my eyes.

I had had time to go and have it removed. The treatments weren’t perfect, but they were pretty decent. But I had written my letters, set things in motion, prepared my mind. I was ready to go. Now. Not in a few weeks, after multiple sessions under the laser to remove one detail.

Mia’s make-up! I sprinted back up the stairs. We seldom came to the castle, but our room had all the stuff we needed; clothes mainly, but also make-up for Mia. She had left her Goth days behind her and I never felt she needed make-up, but an actress without war paint draws the paparazzi and invites magazine pieces commenting on how she’s ageing and speculating on whether she might be ill – all the sort of nonsense I thought society might have outgrown in the new millennium but that we somehow trailed after us like chains linking us to the bad old days. Bad old days I needed to head back to.

I found her collection of flesh-tone foundations and tried brushing some over the tattoo. It actually did a decent job. I mean, it wouldn’t last long, but for short periods when nobody was looking for the tattoo, I very much doubted they would notice. I pocketed a

bunch of the powders and foams then realised I was being an idiot. They would be left behind when I went. Would the make-up, though? I mean, we took our hair with us and that was dead; so was the outer layer of our skin. It was, after all, hard to say where the living body ended. The time travellers didn’t leave their fingernails lying on the clothes left behind. Technically the tattoo ink was dead. Maybe it would settle to the floor as dust. Or perhaps the body’s own bio-generated fields enveloped anything sufficiently close to it and allowed that to be transported, too. Maybe this was what Eva had exploited to bring back the Lewis Carroll book, not to mention her imbedded technology, and to travel clothed.

Either way, it would work or it wouldn’t. I masked the tattoo beneath a layer of foundation then returned to the cave.

It was good that Mia was there to watch me, albeit in the form of the frozen trail through time. A journey that I had taken measures to prevent. I kissed her forehead once, my lips meeting the slickness of the discontinuity that wrapped her time trail. And then, with a last look around and a sigh of resignation, I stepped back into my own long-awaited return.

CHAPTER 18

1985

Dark.

Technically the journey back had taken me no time, but inside it felt as long as it was, it felt as if I had been travelling backwards most of my life. Always in darkness. And so the cold was the thing that alerted me to the fact that I had arrived. The cold and a tiny jolt as I fell the centimetre or so to the floor, the drop occasioned by the fact that my shoes had opted to remain in 2011 and head on into Christmas in the usual way.

I reached out to the side and found Mia’s slick, touch-defying curves readily to hand. That was good. She grounded me. Still in the cave. And gave me orientation in case I lost my own. Her time trail would always be present in the cave in the years between the date of her destination and the date of her departure, whether she used it or not. Part of me felt I had abandoned her, locked her in the future behind Elias Root’s barrier. But if she came back, she would try to stop me. If she succeeded in stopping my sacrifice, she would create a much more dangerous paradox than the one caused by simply not returning along her time trail. If she failed, she would have to watch me die and be stranded in the past with the aftermath.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

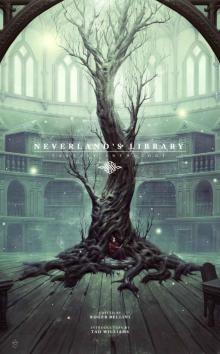

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology