- Home

- Mark Lawrence

King of Thorns be-2 Page 14

King of Thorns be-2 Read online

Page 14

The sight prompted Red Kent to curiosity. “What is a volcano, Jorg?”

“Where the earth bleeds,” I told him. Sim and Grumlow rode in closer to hear. “Where its blood bubbles up. Molten rock, like lead melted for the siege, poured red and runny from the depths.”

“It was a serious question.” Kent turned his horse away, looking offended.

Days later we could smell the sulphur in the air. In places a fine black dust lay on the new leaves even as they unfurled, and stands of trees stood dead, acre after acre bare and brown, waiting for a summer fire.

You know you’re entering the Dane-lore by the troll-stones. You start to see them at crossroads, then by streams, then in circles atop hills. Great blocks of stone set with the old runes, the Norse runes that remember dead gods, the thunder hammer and old one-eye who saw all and told little. They say the Danes choose one rock above another for troll-stones because they see the lines of a troll in some but not the next. All I can say is that trolls must look remarkably like chunks of rock in that case.

We hadn’t seen so many troll-stones before a rider joined us on the road. He came from the south, setting a fast pace and slowing as he caught our band.

“Well met,” he called, standing in his stirrups. A local man, hair braided in two plaits, each ending in a bronze cap worked with serpents, a round iron helm tight on his head and a fine moustache flowing into a short beard.

“Well met,” I said as he drew level at the head of our column. He had a shortbow on his back, a single-bladed axe strapped to his saddlebags, a knife at his hip with a polished bone handle. He gave Gorgoth a wide berth. “You should follow me,” he said.

“Why?”

“My lord of Maladon wishes to see you,” he said. “And it would be easier this way, no?” He grinned. “I’m Sindri, by the way.”

“Lead on,” I said. A band of warriors probably watched us from the woods, and if not, Sindri deserved to be rewarded for his balls.

We followed him a couple of miles along a trail increasingly crowded with traffic, wheeled and on foot or hoof. Occasionally we heard a distant rumble, not unlike a giant version of the lion Taproot had caged, and the ground would tremble.

Sindri led us past two grey villages and brought us along the side of a narrow lake. When the mountains grumbled, the water rippled from shore to shore. The stronghold at the far end looked to be made of timber and turf with only the occasional block of stone showing above the foundations.

“The great hall of the Duke of Dane,” Sindri said. “Alaric Maladon, twenty-seventh of his line.”

Rike snorted behind me. I didn’t bother to silence him. A voice was speaking at the back of my mind, just beyond hearing, a low moan or a howl…a stone face swam across my vision, a gargoyle face.

Men were gathered before the hall, some at work, others preparing for a patrol, each armed with axe and spear, carrying a large round shield of painted wood and hide. Stable hands came to take our horses. As usual Gorgoth drew the stares. When we passed I heard men mutter, “Grendel-kin.”

Sindri ushered us up the steps to the great hall’s entrance. The whole place had a sorry look to it. The black dust coated everything with a fine film. It tickled the throat like a feather. The patrol horses looked thin and unkempt.

“The Duke wants to see us still wearing the road?” I asked, hoping for some hot water and a chair after so many miles in the saddle. A little time to prepare would be good too. I wanted to remember where I knew the name from.

Sindri grinned. Despite the beard, he hadn’t too many years on me. “The Duke isn’t one for niceties. We’re not fussy in the northern courts. The summer is too short.”

I shrugged and followed up the stairs. Two large warriors flanked the doorway, hands on the hafts of double-headed axes, their iron blades resting on the floor between their feet.

“Two of your party should be enough,” Sindri said.

It never hurts to trust someone, especially when you’ve absolutely no other option. “Makin,” I said.

Makin and I followed Sindri into the gloom and smoke of the great hall. The place seemed empty at first, long trestle tables of dark and polished wood, bare save for an abandoned flagon and a hambone. Wood-smoke and ale tempered the stink of dogs and sweat.

At the far end of the hall on a fur-strewn dais in a high oak chair a figure waited. Sindri led the way. I trailed my fingers along the table as we walked, feeling the slickness of the wood.

“Jorg and Makin,” said Sindri to his lord. “Found heading north on your highway, Duke Alaric.”

“Welcome to the Danelands,” the Duke said.

I just watched him. A big man, white-blond hair and a beard down his chest.

The silence stretched.

“They have a monster with them,” Sindri added, embarrassed. “A troll or Grendel-kin, big enough to strangle a horse.”

In my mind a gargoyle howled. “You brought a snow-globe,” I said.

The Duke frowned. “Do I know you, boy?”

“You brought a snow-globe, a toy of the ancients. And I broke it.” It had been a rare gift, he would remember the globe, and perhaps the avarice with which a little boy had stared at it.

“Ancrath?” The Duke’s frown deepened. “Jorg Ancrath?”

“The same.” I made a bow.

“It’s been a long time, young Jorg.” Alaric stamped his foot and several of his warriors entered the hall from a room at the end. “I’ve heard stories about you. My thanks for not killing my idiot son.” He nodded toward Sindri.

“I’m sure the tales have been over-told,” I said. “I’m not a violent man.”

Makin had to cover his mouth at that. Sindri frowned, looking rapidly from me to Makin and back at the Duke.

“So what brings you to the Danelands then, Jorg of Ancrath?” the Duke asked. No time wasted here, no wine or ale offered, no gifts exchanged.

“I’d like some friends in the north,” I said. It hadn’t been part of my thinking but once in a long while I like a man on sight. I’d liked Alaric Maladon on sight eight years earlier when he brought my mother a gift. I liked him now. “This place looks to have missed a harvest or two. Perhaps you need a friend in the south?”

“A plain speaker, eh?” I could see the grin deep in his beard. “Where’s all your southern song and dance, eh? No ‘prithees,’ no ‘beseeching after my health’?”

“I must have dropped all that somewhere on the way,” I said.

“So what do you really want, Jorg of Ancrath?” Alaric asked. “You didn’t ride five hundred miles to learn the axe-dance.”

“Perhaps I just wanted to meet the Vikings,” I said. “But prithee tell me what ails this land. I beseech you.”

He laughed out loud at that. “Real Vikings have salt in their beard and ice on their furs,” he said. “They call us fit-firar, land-men, and have little love for us. My fathers came here a long, long time ago, Jorg. I would rather they stayed by the sea. I may not have salt in my beard but it’s in my blood. I’ve tasted it.” He stamped again and a thickset woman with coiled hair brought out ale, a horn for him and two flagons for us. “When they bury me my son will have to buy the longboat and have it sailed and carted from Osheim. My neighbour had local men make his. Would have sunk before it got out of harbour, if it ever saw the ocean.”

We drank our ale, bitter stuff, salted as if everything had to remind these folk of their lost seas. I set my flagon on the table and the ground shook, harder than any of the times before, as if I had made it happen. Dust sifted from the rafters, caught here and there by sunlight spearing through high windows.

“Unless you can tame volcanoes, Jorg, you’ll not find much to be done for Maladon,” Alaric said.

“Can’t Ferrakind send them to sleep for you?” I asked. I’d read that volcanoes slept, sometimes for a lifetime, sometimes longer.

Alaric raised a hairy brow at that. Behind us, Sindri laughed. “Ferrakind stirs them up,” he said. “Gods rot hi

m.”

“And you let him live?” I asked.

The Duke of Maladon glanced at his fireplace as if an enemy might be squatting there among the ashes. “There’s no killing a fire-mage, not a true one. He’s like summer-burning in a dry forest. Stamp out the flames and they spring back up from the hot ground.”

“Why does he do it?” I knocked back the last of my salt beer and grimaced. Almost as bad as the absinthe.

“It’s his nature.” Alaric shrugged. “When men look too long into the fire it looks back into them. It burns out what makes them men. I think he speaks with the jotnar behind the flames. He wants to bring a second Ragnarok.”

“And you’re going to let him?” I asked. I cared little enough for jotnar, or any other kind of spirit. Push far enough past anything, be it fire or sky or even death, and you’ll find the creatures that have always dwelt there. Call them what you will. “I heard tell there was no problem that a Dane couldn’t cut through with an axe.” It’s a dangerous business questioning a man’s courage in his own hall, especially a Viking’s, but if ever a place needed shaking up then this was it.

“Meet him before you judge us, Jorg,” Alaric said. He sipped from his ale horn.

I had expected a more heated response, perhaps a violent one. The Duke looked tired, as if something had burned out of him too.

“In truth I came to meet him,” I said.

“I’ll take you,” Sindri said, without hesitation.

“No.” His father, just as fast.

“How many sons do you have, Duke Maladon?” I asked.

“You see him.” Alaric nodded to Sindri. “I had four born alive. The eldest three burned in the Heimrift. You should go home, Jorg Ancrath. There’s nothing for you in the mountains.”

18

Four years earlier

Sindri caught us up before we’d got five miles from his father’s hall. I’d left Makin with Duke Alaric. Makin had a way with the finding of common ground and the building of friendships. I left Rike too, because he would only moan about climbing mountains and because if anyone could show the Danes true berserker spirit it was Rike. I left Red Kent also, for his Norse blood on his father’s side and because he wanted a good axe made for him.

“Well met,” I said as Sindri rode up between the pines. It had never been in doubt that he would give chase. He found us as we left the lower slopes and thick forest behind.

“You need me,” he said. “I know these mountains.”

“We do need you,” I said.

Sindri grinned. He took off his helm and wiped the sweat from his brow, blowing hard from the ride. “They say you destroyed half of Gelleth,” he said. He looked doubtful.

“Closer to a fifth,” I said. “Legends grow in the telling.”

Sindri frowned. “How old are you?”

I felt the Brothers stiffen. It can be annoying to always have the people around you think you’re going to murder everyone who looks at you wrong. “I’m old enough to play with fire,” I said. I pointed to the largest of the mountains ahead. “That one’s a volcano. The smoke gives it away. What about the rest?”

“That’s Lorgholt. Three others have spoken in my lifetime,” Sindri said. “Loki, Minrhir, and Vallas.” He pointed them out in turn. Vallas had the faintest wisps of smoke or steam rising from its western flanks. “In the oldest eddas the stories tell of Halradra being the father and these four his sons.” Sindri pointed to the low bulk of Halradra. “But he has slept for centuries.”

“Let’s go there then,” I said. “I’d like to watch a sleeping giant before I poke a woken-up one.”

“These aren’t people, Jorg,” Makin had told me before we left. “They’re not enemies. You can’t fight them.”

He didn’t know what I thought I could achieve wandering the landscape. I didn’t either but it always pays to have a look around. If I think back on my successes, such as they are, they come as often as not from the simple exercise of putting two disparate facts together and making a weapon of them. I destroyed Gelleth with two facts that when laid one atop the other, made something dangerous. There’s a thing like that at the heart of the Builders’ weapons, two chunks of magic, harmless enough on their own but forming some critical mass when pushed together.

The Halradra is not so tall as its sons, but it is tall. Its lower slopes are softened by the years, black grit in the main, crunching under hoof, the rocks rotten with bubbles so that you can crumble them in your hands, the fire so long gone that no sniff of it remains. Through the ash and broken rock, fire-weed grew in profusion, Rosebay Willowherb as they had it in Master Lundist’s books. The first to spring up where the fire has been. Even after four hundred years nothing much else wanted to push its way through the black dirt.

“Do you see them?” Gorgoth rumbled at my shoulder. The depth of his voice took me by surprise as always.

“If by ‘them’ you mean mountains, then yes. Otherwise, no.”

He pointed with one thick finger, almost the width of Gog’s forearm. “Caves.”

I still didn’t see them, but in the end I did. Cave mouths at the base of a sharp fall. Not that dissimilar from Gorgoth’s old home beneath Mount Honas.

“Yes,” I said. “They are.” I thought that sometimes perhaps Gorgoth should just keep holding on to those precious words.

We pressed on. Higher up and the going gets too steep and too treacherous for horses. We left our mounts with Sim and Grumlow, continuing on foot, trudging on through a thin layer of icy snow. The peaks of Halradra’s sons look broken off, jagged, forged with violence. The old man could pass as a common mountain with no hint of a crater until you scramble up through snow-choked gullies and find the lake laid out before you, sudden and without announcement.

“Happy now?” Sindri climbed up beside me and found a perch where the wind had taken the snow from a rock. He looked happy enough himself despite his tone.

“It’s a sight and a half, isn’t it?” I said.

Gorgoth clambered up with Gog on his shoulder.

“I like this mountain,” Gog said. “It has a heart.”

“The lake is a strange blue,” I said. “Is the water tainted?”

“Ice,” Sindri said. “The water’s just meltwater, a yard deep if that, run down off the crater slope. The lake stays frozen all year, underneath.”

“Well now. There’s a thing,” I said. And I had two facts by the corners.

We hunkered down in the lee of some rocks a little way below the crater rim and watched the strange blue of those waters as we ate a cold meal from Alaric’s kitchens.

“What kind of heart does the mountain have, Gog?” I threw chicken bones down the slope and licked the grease from my fingers.

He paused, closing his eyes to think. “Old, slow, warm.”

“Does it beat?” I asked.

“Four times,” Gog said.

“Since we started climbing?”

“Since we saw the smoke as we rode in from the bridge,” Gog said.

“Eagle.” Row pointed into the hazy blue above us. He reached for his bow.

“Good eyes as always, Row.” I held his arm. “Let the bird fly.”

“So,” said Sindri, huddled, braids flailing in the wind. “What next?”

“I’d like to see those caves,” I said. Gorgoth’s observation felt more important all of a sudden. Precious even.

We started to make our way down, strangely a more difficult proposition than the climb, as if Halradra wanted to keep hold of us. The rock seemed to crumble under every heavy downhill step, with the ice to help any faller on his way. I caught Sindri at one turn, grabbing his elbow as the ground broke away under his heel.

“Thanks,” he said.

“Alaric wouldn’t be pleased to lose another son up here,” I said.

Sindri laughed. “I would have stopped at the bottom.”

Gorgoth followed, kicking footholds for himself at each step; Gog scampered free rather than risk getting squashed

if the giant fell.

We found Sim and Grumlow sharing a pipe, sprawled on the rocks in the sunshine all at ease.

The caves were almost harder to see as we drew closer. Black caves in a black cliff with black interiors. I spotted three entrances, one big enough to grow an oak in.

“Something lives here,” Gorgoth said.

I looked for signs, bones or scat around the cave mouth. “There’s nothing,” I said. “What makes you say there is?”

Expressions came hard to a face like Gorgoth’s, but enough of the ridges and furrows moved to let a keen observer know that something puzzled him. “I can hear them,” he said.

“Keen ears and keen eyes. I can’t hear anything. Just the wind.” I stopped and closed my eyes as Tutor Lundist taught me, and let the wind blow. I let the mountain noises flow through me. I counted away the beat of my heart and the sigh of breath. Nothing.

“I hear them,” Gorgoth said.

“Let’s go careful then,” I said. “Time for your bow, Brother Row, good thing you didn’t waste an arrow on that bird.”

We tethered the horses and made ready. I took my sword in hand. Sindri unslung the axe from his back, a fine weapon with silver-chased scrollwork on the blade behind the cutting edge. And we moved in closer. I led in from downwind, an old habit that cost us half an hour traversing the slopes. From fifty yards the wind brought a hint of the inhabitants, an animal stink, faint but rank. “Our friends keep a clean front doorstep,” I said. “Not bears or mountain cats. Can you still hear them, Gorgoth?”

He nodded. “They’re talking about food, and battle.”

“Curiouser and curiouser,” I said. I could hear nothing.

We came by slow steps to the great cave mouth flanked by two smaller mouths and several cracks a man might slip through. Standing before the cave it seemed impossible that I had missed it from across the slopes. Apart from one shattered bone wedged between two rocks there was no sign of habitation. Except for the stink.

Gorgoth stepped in first. He carried a crude flail in his belt, just three thick chains on a wooden haft, set with twists of sharp metal. A leather apron kept the chains from shredding his legs as he ran. I’d never seen him take the weapon in hand, and somehow he seemed more scary unarmed. Gog walked behind Gorgoth with Sindri and me to flank him, then Sim and Grumlow, Row at the rear eyeing everything with suspicion.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

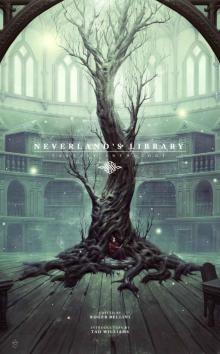

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology