- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Page 13

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Read online

Page 13

‘The universe has tried that on me before. You learn to live with it.’ I’d explained to her how it worked, how when it had happened to me there always seemed to be a way to step around the threat into one of the timelines where I survived. ‘Also, once the travel barrier is in place, my calculations show it will help shield us from those effects. Ellery was just unlucky to die before he understood what was happening to him.’

‘Hmmm.’ Mia seemed unconvinced.

‘The main thing for now is to see you safely through into 2012.’ I walked on, frowning. ‘I just wish I could put you in a box out of harm’s way.’

Mia dug her nails into my hand as we stepped through the doors. ‘Just try it.’

‘I could send you forward!’ I stopped halfway in, the elevator doors unable to close. ‘Just a year. You’d be in transit. Nothing could hurt you. I could send you into 2012 and it would all be over! It’s genius!’

Mia frowned. ‘Unless Demus lied about it happening in 2011.’ She always called him Demus, never ‘you’.

‘Why would I lie?’ I asked.

Mia shrugged. ‘Demus lied about just appearing in front of that police station. Why would his lies end there?’

I stepped into the elevator and pushed the button. ‘Why would I lie to myself?’ That bit had never made sense to me.

The plan was too perfect, too simple, for Mia to resist in the long run. I would send her forward into 2012. She’d be out of action for a year, but she had no major roles coming up for a while anyway and it wasn’t as if she needed the money. I would miss her, of course, but a lost year compared to her suffering a massive injury and brain trauma in 2011 seemed an easy choice. Ideally, I would have just travelled with her, but it seemed safer to have one of us still active, and I wasn’t the one in danger.

I set her travelling in the cave beneath the Tower of Tricks, since I had all the right equipment there and didn’t want her stuck in one of those government-approved warehouses. The nearest one, down in London, was actually closer to our Cambridge home, but having her travel at the Tower of Tricks meant I could visit her whenever I wanted and in private, rather than on scheduled appointments with a crowd of relatives strolling around the frozen ranks in London like it was a waxwork museum.

Everything was fine until the call I got on my landline at work in late October 2011.

‘Nick?’ A woman’s voice.

‘Hello, yes?’ I was sitting at my desk, avoiding administration niff-naff in favour of a tricky bit of paradoxical algebra requiring the use of not only imaginary numbers but hypothetical ones, too.

‘It’s me,’ she said.

I looked up from my calculations at that, shaking the equations from my head. ‘Mia?’

‘You’ve forgotten my voice already?’ A hint of amusement.

‘But . . . it’s too early. I sent you forward a year.’

‘Yet, here I am.’ Something rattled. ‘Making breakfast at four in the afternoon.’ A clatter of spoon in bowl. ‘Did you miss me?’

‘Of course I did . . . but—’

‘If you set off now you could be here in time for bed,’ she said. ‘And you could show me how much.’

‘I’m putting my coat on as we speak,’ I lied. I had missed her, though. ‘I’ll be there as soon as I can. Do. Not. Go. Anywhere.’

‘Yes, Master.’

‘Seriously. This shouldn’t have happened. I need to find out why and you need to stay safe. Lock everything! Don’t go near anything sharp or hot or—’

She hung up on me.

I drove at unsafe speeds and got speeding tickets from two different police forces. But it wasn’t me who was in danger of a massive head trauma, it was Mia, who had mysteriously emerged from her time trail, where she would have been safe from a close-proximity nuclear explosion, into a castle where not so very long ago a man had been killed by two kilos of ceiling plaster.

It had been dark for hours by the time I reached the castle. It stood unlit, a black fist among the silent fields of solar arrays. Behind it the great blades of wind turbines turned at their leisure in a gentle breeze. I activated the portcullises at a distance and roared through in my BMW, coming to a screeching halt in the main courtyard. From there I could see lights burning in the kitchen.

‘Mia!’ I pounded on the main door, heart thudding. She’d set the bolts, so at least she had listened to something I said.

A few moments later the bolts were drawn, the door opened, and there she was, her face a mixture of pleased and cautious.

‘Mia!’ It felt good to hold her in my arms again. I’d known that I had missed her: a dull ache on which I piled endless work to distract me. But pulling her to me, the relief was something physical, as if her absence had been a slowly increasing weight now removed in one instant.

‘Whoa there, stallion.’ She pushed herself free, grinning. ‘I should go on these trips more often.’

I grinned back. ‘Don’t.’

I knew that to Mia we had said goodbye a few hours ago, so I wasn’t hurt by her more reserved greeting. And since I had some serious investigation to do, it was probably for the best that she wasn’t feeling the separation the same way I did, or we’d have both headed for the bedroom and the night would have been wasted. Well, not wasted, but not productive when it came to answering the most important question: what the hell was going on?

We went back to the traveller cave where the equipment that had sent Mia forward still stood, enclosing the space she had until so recently occupied.

‘The easiest test to run is just to repeat the exercise,’ I said.

‘I’m game.’ Mia started towards the towering magnets.

‘Not you. This could be how you get injured, for all we know.’

‘Well, we can’t send you!’ Mia said. ‘If it went wrong, who would figure out how to fix it?’

‘This is why we should keep guinea pigs,’ I said.

‘Nuh-uh. That’s vivisection. Besides, we don’t visit often enough. They’d starve.’

‘I think vivisection means you have to cut the animals up afterwards rather than just experiment on them. But’ – I raised my hand, seeing that she was about to argue – ‘this will do.’ I bent to scoop up a woodlouse I’d just spotted crawling across nearby cabling. The lights had given the cave a whole new ecosystem over the years.

I put the bug in an abandoned coffee mug and set it where Mia had stood. The readouts on my shielded computer indicated that the capacitor banks above ground held sufficient charge for a forward journey, so I initiated the sequence.

The magnets emitted their normal creaks and groans as huge currents flowed around them. The resulting magnetic fields fluctuated in a swift but complex three-dimensional pattern, building a resonance within the fabric of space-time, pouring in more and more energy until the vibrations grew so large that a bubble of space-time should detach itself from the rest – just as the surface of a body of water may throw up a single droplet, breaking free of the surface tension, if the right frequency of sound is played through it at sufficient volume.

Stray magnetic fields escaped the array as usual, giving me a momentary trippy feeling, as if I were larger than my body, a god with boundless power who could step outside the universe and behold it all as a gem containing time within it, all the years from the Big Bang onward held as a single vision. The sensation passed, leaving me back in my own flesh with that familiar disappointment at having something glorious snatched from my grasp.

Mia went forward as the creaking died away and peered into the mug. ‘Nope. Ol’ crawly is still crawling.’ She frowned. ‘Should it work on bugs, anyhow? I thought it was about consciousness, not just life.’

‘Maybe . . .’ I hadn’t ever tested it. I examined the read-outs. ‘Doesn’t matter, though. No completion . . .’ The necessary power had been delivered, the components all seemed to be working, but the resonance hadn’t reached the levels required to break free the bubble of space-time that was supposed to be the veh

icle in which our woodlouse would speed into the future. The complex pattern of reinforcing feedback cycles feeding energy in at a rate calibrated to the elasticity of local space-time should have built relentlessly to reach the target level. But they hadn’t even come close. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘Maybe someone blocked it,’ Mia said.

‘Don’t be silly, how could th—’ But then I saw it. There in the background readings. It shouldn’t have been possible, but she was right. Exactly right. Someone had discovered my barrier theory and made their own.

CHAPTER 15

2011

When you are going to disbelieve an illusion, you need some kind of act of faith to strengthen you, to show your resolve and commit you to your course. Standing there with Mia in the travellers’ cave facing the only two remaining time trails, mine and hers, I already had my act of faith in hand, or rather, ‘on hand’. While Mia had been safe, speeding into 2012, I’d had my first ever tattoo done, a closed integral, , set across the back of my right hand. I actually asked for an infinity sign, ∞, but when the tattooist asked what it was and I showed him and he said, ‘Eight?’, I thought better of it. The point was that I now had a tattoo and Demus, both the one standing there before me and the one in my memory, did not.

‘Shit.’ I flicked through more screens of data in the vain hope they would suggest a different answer. They didn’t. ‘Someone has set up a barrier.’

‘I thought nobody was that close yet,’ Mia said.

‘So did I.’ I opened an internet browser and hit the BBC News website. ‘Nothing in the headlines, and it’s been hours now.’

‘Headlines?’ Mia blinked.

‘If this was a decent attempt, it would have covered the whole country. All the government facilities where they keep the forward travellers would be full of rather confused people right now making angry noises. The lack of news suggests they’re all still statues. Which in turn suggests that this is a localised effect. Whoever is causing it may not fully realise what they are doing. I’m guessing it’s one of the universities nearby. All the physics departments have their own research rigs now.’

‘So, we can’t go back now? Even if we wanted to?’ Mia’s gaze returned to her time trail. We had removed the covers, since nobody else would be coming into the cave again. At least not before the trails had vanished. ‘What will happen? You know, about the paradox, if we don’t go?’

‘I’m not worried about that,’ I said. Though I was. ‘I’m worried that they’ll boost the power and block the whole country before they know what they’re doing.’

‘Why would that be a problem?’

‘Rust and Guilder would hit it. And Guilder would see me as his best chance to fix the problem.’ Even as I said it, I wondered just how large an area was blocked right now and whether Guilder’s hideout was affected. ‘We need to get you some security.’

Mia shook her head. ‘I don’t need a bodyguard. Some beetle-browed thug following me everywhere.’

‘You do, and more than one,’ I said. And seeing her mouth opening to protest I added, ‘No Neanderthals, I promise. Jason Stathams, all of them. Two hundred and fifty pounds of hard muscle packed into a suit.’

She pursed her lips and pretended to consider it.

In the end, I hired the men and had them trail her covertly. Relationships should be based on trust, but until 2012 had been sung in on New Year’s Eve and the clock had struck midnight, my relationship with Mia was based on fear: the fear that she would meet her long-prophesied accident and the competing fear that Charles Rust would find her and steal her, holding her a prisoner against my solving an impossible problem for his boss.

I spent the days after Mia’s return to our time stream hunting down the source of the barrier. Rather than wander the countryside with the heavy gear necessary to detect it, I delegated that task to hired hands and organised the effort from my office as director of the National Institute for Temporal Studies, or NITS as it was more commonly referred to.

Unfortunately, no matter how much money you happen to have, some specialist equipment just can’t be had on demand, so I could only muster four trucks, which I sent out to hunt the edges of the barrier and map its strength in an attempt to estimate the source. I felt pretty sure I would only have to locate it with sufficient accuracy to say which university city it was nearest to. At that point I would know where to find the equipment and could hopefully buy off whoever was experimenting with it.

It was important for the researcher not to extend the area, as that would increase the risk of bringing Guilder and Rust’s journey to an end – though the current barrier might have already done so. My plan would bring their forward trip to an end soon anyway, but I wanted it to be next year at the very earliest. Additionally, if the barrier did reach London and bring all the travellers there to a halt, it would be very hard to hush up the technology, and if Mia did get hurt I still needed the option to go back to 1986 to ensure her recovery.

My mind whirled around all these competing desires, needs and possibilities, and, as they did so often at such times, my eyes returned to the closed integral tattoo on the back of my hand. Barrier or no barrier, that was an act I had taken myself to put a wall between me and Demus. At the time it had felt like a bold move; a brave one, even. But with Mia in jeopardy once more, it suddenly seemed like a very selfish decision.

Six days after the barrier went up, I was still at my desk in the NITS head office. On the screen in front of me a map of the UK glowed in glorious technicolour, shaded to indicate the likelihood of any given point being the source for the barrier. My software updated it each time new measurements were sent from the mobile units that I had out criss-crossing the country. I divided my time between refining the algorithms that calculated the probabilities and staring moodily at the screen. The latest data had shifted the bulk of certainty towards the Midlands, centred on Coventry, with Birmingham and Warwick almost as likely. I’d phoned to order a car to drive me to Warwick and had annoyingly been put on hold before I could protest. Instead of just calling a different company, I let my eyes return to staring at the hypnotic colours of the map, and found myself once more pondering my connection with Demus. I was still on hold and daydreaming when someone shook my shoulder.

‘Nick?’ The hand shook me again. ‘Nick! Did you hear anything I said?’

I looked up. Neil Watkins, my assistant director. ‘They’ve been trying to reach you. Mia’s been in an accident. You need to get to the hospital.’

And that’s how Mia and I ended up trying to escape Addenbrookes Hospital covertly, expecting that at any minute Charles Rust might come limping out of the shadows with murder in his eye and a silenced pistol in his hand.

Fortunately, the hospital had been surgically attached to a Burger House, perhaps so those overdosing on triple-decked layers of beef with double cheese could have their obese bodies wheeled directly to the coronary ward. In any event, it meant that along with the obligatory link in a chain of coffee franchises, there were plenty of ways in and out of the place with a steady flow of people.

We mingled with the burger munchers and left keeping our heads down. We abandoned my car in favour of a taxi summoned while still inside the hospital.

‘I should call the police,’ I said.

‘And tell them what?’ Mia asked.

‘Rust has a string of charges outstanding after the investigation.’

‘So I tell them I might have been attacked by a man nobody has seen for twenty years and who should be fifty now, but isn’t?’ Mia shook her head. ‘Turn left at the next lights,’ she called out to our driver.

‘We shouldn’t go home,’ I said.

‘Where, then?’

‘The castle.’ I nodded to myself. ‘It’s secure and we can see him coming. In town he can just ghost up on us out of any crowd.’

And so the rather surprised taxi driver found himself being offered a large sum of money to drive two lunatics across the width of the

country.

We left Cambridge on the A428 heading west and were soon driving through rural England, free and clear; or at least we would be until the next time Rust – it had to be him, nothing else made sense – tracked us down again. I wasn’t sure what the long-term solution was. Perhaps that’s why Mia and I still had time trails standing in the cave: we said to hell with paradox and ran to the past together to escape Rust once and for all. Maybe I decided not to show up for my death scene and just dared the universe to do its worst. At least Mia would be with me. It wasn’t the worst plan in the world, though I would miss some of the folks we’d have to leave behind. Also, I wasn’t sure how long I could survive without the internet.

I called John and Simon just to let them know what the situation was and got their voicemails in both cases. I left word for them, then turned round to give my phone to Mia on the back seat so she could call her mother, who against all predictions was still alive, and still consuming cigarettes and whiskey at a frankly scary rate of knots.

My thoughts returned to the cave. We wouldn’t be running anywhere, future or past, unless I got that barrier down. I was pretty sure I could knock out the generator causing the disruption and open a window for me and Mia to get away into the past. Rust, however, would want more than that. He would want me to knock out all barriers ever, or at least until he and Guilder had got as far into the future as they wanted. And that I could not do. The cat was out of the bag now. Whoever was generating the current barrier would be busy telling the planet about the technology soon enough. It wouldn’t take so very long before the world’s scientific community managed collectively to solve the reverse travel problem. I’d been edging them slowly towards it, more out of pride than need; I’ll admit it stung me to think someone else would be credited with the discovery. Once that particular can of worms was opened, and the dangers of paradox identified, then governments everywhere would ban it. And once governments started operating their own temporal barriers, the shutters would come down on the whole technology. There was nothing I could do about it. Only, Rust wouldn’t see it that way. He’d taken Guilder’s money, accepted an obligation, and from what I knew about the man he wouldn’t give up on that, no matter who he had to cut into pieces trying to make it happen.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

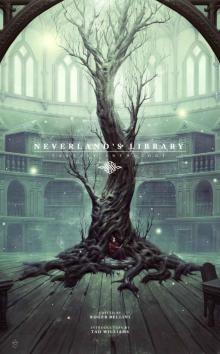

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology