- Home

- Mark Lawrence

Road Brothers Page 10

Road Brothers Read online

Page 10

“I wanted to see you go home,” Harrac said. The Snake-Stick would find them soon. The bush offered many places to hide but the surviving Laccoa left a trail any skilled hunter could follow and they didn’t have time to disguise it further.

“I was tracking raiders,” Snaga said, glancing back at Harrac. “Not going home.”

Harrac watched the Viking and said nothing. As leader of the fifth Laccoa division Snaga had the right to make such decisions, but tracking Snake-Stick raiders for ten days had taken them far beyond prudence, out past the furthest reaches of the king-of-many-tribes’s influence. Out to lands where even the Laccoa must tread lightly. The Snake-Stick raiders had led them into Ugand territory and set up an ambush with their allies.

Snaga grinned. “I always said the only way home for me was with a band of brothers around me.” He looked around at the Laccoa, their ranks thinned but the core of their strength remaining. “We made it further than I expected. Another week and I could have shown you the sea!”

“I would liked to have seen it,” Harrac said. “The gods were not with us though.”

Snaga pointed to the east. “You have the command, Firestone. Take the men and head back. If you reach the grey scrub you’ll stand a good chance. When the Snake-Sticks come disperse and make separately to the great rocks we saw after the river.”

“It’s a good plan. Harrac sat back in the creoat bush and ran his whetstone along the length of his blade another time. “Why are you telling me to lead?”

“I’m going back along our trail to make an ambush of my own. You know what I can do if I get in amongst them.”

Harrac didn’t argue. He knew where that led. He gathered the men and told them the plan while Snaga crouched a way off, scanning the bush. Nine of the Laccoa would not leave without arguing. Harrac sent them to Snaga and the big man held each by the shoulder, speaking softly to them, extracting a promise. They returned one by one. Hard men, killers, eyes red.

Harrac led the band away.

Snaga found his spot a few hundred yards back along their trail. The Snake-Sticks were close now, some still letting their dust rise to spook the Laccoa, others moving with more skill, almost unseen save for the occasional alarm cries of a kessot or the flutter of minta birds taking flight.

Snaga rolled under the skeletal branches of a thellot bush, letting the dust cake him, drawing about him armfuls of the ancient seedpod cases that lie in drifts beneath the thellot. Thus disguised he lay in wait.

The hunting party came by presently, confident in their numbers though stepping carefully so as to raise the dust only to waist height. Three slender long-haired Snake-Sticks led an Ugand war-party, squat men with long thin spears and heavy clubs of knotwood. Three dozen in all perhaps.

Snaga rose silently and ran into the midst of them while a Snake-Stick tracker paused to study the confusion in the trail. The Viking loosed his roar only at the last moment when the majority had turned their heads, if not their spears, his way.

His heavy sword sheared through the neck of the first man he reached, ploughing on to slice the next from collarbone to hip. The thrust of his foot broke a man’s knee. He drove his pommel into an Ugand’s face then spun, arm stretched, scything his blade through every man within his arc. The dust rose about him, battlefield smoke, the dark shapes of men closing on every side. Red slaughter followed.

Snaga lay on the ground, head raised, resting on the leg of a dead Ugand. The Ugand dead sprawled on all sides, the dust spattered with their blood, reaching out in dark arcs in all directions, too much even for the thirsty ground to swallow. Close on forty men butchered, tumbled in untidy heaps, broken limbed, red gore spread wide.

Three spears pierced the Viking, gut, thigh, chest. Harrac knew at least two of them were fatal wounds. His own leg had given out, perhaps broken, his eye closed by an Ugand club.

“You came back. I told you not to.” The blood around the spear in Snaga’s chest bubbled as he spoke.

“Just six of us. Aloor is leading the rest back as you ordered.”

“How many ... now...”

“Only me and you, I think. Some of the Ugand ran away.”

“They’ll bring the other parties quick enough.”

Harrac nodded and pulled himself closer to the Viking, wondering if the other men of the Viking tribe were as deadly. He would guess that Snaga had felled twenty of the enemy by his own hand. Even with the spears in him he had fought on, snapping off the hafts – falling only when there were no foes left to stand against him.

“I-” Snaga coughed crimson. “I’ll tell you a Haccu secret.”

Harrac grinned. He hoped the Ugand would kill him quickly. “You don’t know any Haccu secrets, old man.”

“Harrac.” Snaga had never spoken his name before. He paused as if forgetting where he was. “My other son is called Snorri. You would like him.” Snaga set a hand to Harrac’s shoulder. “You Haccu with your secret names.” He coughed again. “But the old Haccu, the wise ones, know this truth.” His voice faded and Harrac leaned in to hear, wincing at the pain in his ribs. “Your secret names are gifts, to share with those you honour or love – but it’s your use-names, the ones young boys are so eager to shed, that say the most about you. The names you wear in full view, simple, ordinary, shared with friend and foe alike. That’s where the truth lies. The stories behind them are the stories of where you came from ... where you’re going.”

Harrac saw the shapes of men, moving through the bush on several sides now. He reached for his sword, dulled by use, the point snapped off, lost in some Ugand’s corpse. “I won’t let them take me.”

“Find something worth holding to.” Snaga didn’t seem to hear him, his eyes fixed on the sky, sharing the same faded blue. His fingers gripped Harrac’s shoulder with surprising strength. “Tell my boy ... tell Snorri...” And the hand fell away.

The Ugand broke cover, screaming, and as Harrac struggled to stand a heavy net fell about him from behind. He tripped and fell, roaring. The first of the screaming Ugand reached him, spear raised to skewer him. Snaga’s sword carved the leg from under the man. A second Ugand drove his spear through Snaga’s neck but the Snake-Stick who had netted Harrac stepped over his prey to guard it.

Harrac lay unmoving, eyes on Snaga, now pierced by still more spears as if the Ugand couldn’t believe so big a man truly dead. The Snake-Sticks would sell him north, a prize Laccoa, a fighting slave for some sultan’s army or the blood-pits of a merchant prince. Snaga had said his life didn’t end when they put chains upon him – Harrac too would endure. The net tightened about him and he said nothing.

Snaga had found him at the gates, a boy-turned-man, angry, with blood on his hands, and he had held to him. Perhaps to replace his own lost son, but there was no shame in that. Snaga had spoken of Harrac, offering guidance, but so often he truly spoke of himself, his own struggles, his own choices. Snaga had been right though. Firestone was the name that said most about its owner and Harrac had worn it without shame before those he loved. Both of them, Snaga and Harrac were men who looked for something to commit to – something to guard – and once sworn to their cause both would die for it.

Harrac grunted as they lifted him in his net, the Snake-Sticks carrying him, hanging from a pole between four men, the Ugand whooping around, raising dust, thick as their anger. He watched until the bodies of friend and foe became lost. He travelled unseeing now, cocooned in the net, hemmed in by bodies. Perhaps it was like this to travel the oceans, swaying and bouncing with the waves. He had no knowing what lay ahead of him. Things as far beyond his imagination as Ibowen had been when he first walked from his village. Maybe there would even be snow. All he knew was that he would carry his name with him, Firestone. He had asked Snaga how it would sound in northern mouths.

“Kashta, my friend. That’s how we would speak it. Kashta. It’s good name. Hold it close.”

Footnote – I enjoyed writing this one. We see the father of Snorri ver Snagason’s (from T

he Red Queen’s War trilogy) and the Nuban as a young man. We see some similarities between the young Firestone and the young Jorg, and perhaps understand the relationship between them a little better.

Choices

“They say knowledge is power. But I know everything and have no power.” Jane gazed out across the dark lake. Her reflection burned there and the surface threw her glow at the cavern roof, each ripple written in light across the stone.

“You know everything that will happen. You could rule the world.” Gorgoth sat upon the shingle beach beside his sister, the water at his heels. “Instead we hide among the roots of a poisoned mountain.” Jane almost never spoke. She hadn’t answered a question in years, and though he loved her, her silence made him grind his teeth. To find her almost talkative filled him with both hope and fear in equal measure. “Are you going to tell me where Alithea has taken her babies?”

“Did you know that it is impossible for me to be good or evil, little brother?” She looked up at him, her eyes full of sunlight, her skin like molten silver across which shadows flowed.

“That’s not true,” he said. Time had burned its fingers on Jane and left off touching her after her tenth year. Gorgoth stood twice her height and outweighed her ten times over, but still his older sister awed him. Among all the leucrota she alone was perfect, formed in Eve’s shape, not a single deformity. Just the light that shone from her. He had always taken it for goodness – no matter what Jane had to say about it. “You have choices.”

“I’ve seen the choices I will make. It’s not in me to act otherwise. They are the right choices. But they were made before I opened my eyes to the world.”

“And Alithea?” Gorgoth asked without hope of an answer.

“You know why she ran.” Jane’s light flickered and for a heartbeat the cavern’s ancient night restored itself. There was a lesson there. Darkness is patient, always waiting for its chance, and swift to take it.

Gorgoth nodded to himself. “I know.” The boys were changing too swiftly. Every leucrota changed as they grew – save for Jane – but if the changes came too swiftly the child would die horribly and that death would be dangerous for everyone around them. Gorgoth remembered his own changes, the thickening and reddening of his skin, the alteration of his face. At least the poison had compensated his appearance with great size and strength. He just had to look at his fellow leucrota to see the winning hand he had been dealt: no sores, no weakness, no limbs withered or twisted.

“I should go and hunt for her.” Gorgoth stood, the shingle clattering beneath him.

Jane said nothing, only sat, small and bright, beside the darkness of the lake.

A growl rose in Gorgoth’s chest. “Jane!”

Jane looked up, and Gorgoth’s pupils narrowed to slits against the brilliance of her regard.

“She’s our sister, Jane!” Gorgoth kicked a shower of stones out across the water, peppering the still surface. “You must know how to help her … how to help our nephews.” If he found them they would be surrendered to the necromancers, an unholy exchange of doomed flesh to preserve the poisoned flesh of the leucrotas. If he didn’t find them, they would die a slower and more painful death, alone in the dark, and some other leucrota would have to be sacrificed to the necromancers’ hunger to save the tribe.

“Of course I know.” Her voice came closer to anger than he had ever heard it. “I have known you would ask me since before you were born, brother. And I have no reply for you. Do you still think me good?”

Gorgoth turned his back on her and began to walk toward the distant tunnels that would take him deeper into the mountain. He paused as he reached the larger rocks. “Yes, I think you good.”

“When I close my eyes, Gorgoth. Every time I close my eyes, I see the future. All of it. And all of the past. A glowing structure of light and air that reaches through the rock, through the mountain, out to infinity. Endlessly complex. Whole. There is no ‘now’ to it. Every part of it is a ‘now’. And I could look at it forever.” She turned and Gorgoth’s shadow swirled about him. “And when I open my eyes I am reduced to this … speck … this ‘now’, a point of no dimension travelling along a single thread in all that grand and beautiful chaos. And I come here for you, brother. For you and the others.” She fell silent and Gorgoth watched his shadow, wondering, feeling her light blaze across his shoulders. “One day you will all see it too.”

“You never talk this much!” A sudden conviction seized Gorgoth and squeezed itself from his throat. “You’re going to die soon.” His eyes prickled.

“You’re the soothsayer now, little brother?” She laughed. A warm thing. “Go and do what you will do. Change is coming. For this mountain. For all of us.”

And Gorgoth stood in wonder for his sister had never laughed, not once in all her life, for laughter is a form of surprise.

Gorgoth took Hemmac with him into the deep caves. Hemmac’s nose wasn’t quite as keen as Elan’s, but he was a lot quicker on his feet. Jane had once told Gorgoth the tribe had been named leucrota after the mythical monsters who spoke with a human voice. A cruel jibe from their enemies but less cruel than the spears and arrows that finally drove the leucrota to ground beneath Mount Honas. The mountain had been bleeding poison from its veins since the Day of a Thousand Suns. Every stream that issued from it ran clear and deadly, no fish or weed braving its waters. No tree would grow within fifty yards of the banks. The toxins beneath the mountain had twisted the tribe, occasionally squeezing out a miracle like Jane, but for the most part delivering children who would sicken, deform, and often die. The bit that Gorgoth had never figured out was why his ancestors were known as leucrota before they were driven into the caves.

“This way.” Hemmac lifted his head from the ground and advanced on all fours, sniffing. The raised nodules all along his spine cast strange shadows in the light of Gorgoth’s glow-bar. They followed the path of a long-vanished river that had chewed its way through the rock an age before man first climbed the slopes outside. In time the natural passage intersected a Builder tunnel. A bridge of poured stone had once crossed the passage to allow the Builder tunnel to continue without deviation, but it had fallen centuries ago and the supports were now a mess of broken stone threaded with rusting bars of steel.

“Up.” Hemmac nodded toward the Builder tunnel. The glow-bar’s light glistened on the sores across the left side of his head. The glow-bar was always much brighter close to Builder tunnels. Inside the tunnels it burned so fiercely it almost equalled Jane at full flow.

Gorgoth scrambled up, his short talons finding purchase. From the Builder tunnel he reached down to haul Hemmac up behind him. They progressed then through the ordered labyrinth of the Builders. In places they picked their way across falls of fractured Builder-stone, fallen from the walls to expose the natural rock beneath, gouged by the teeth of some great machine. Here and there shafts led vertically to other levels both above and below. At one junction the poured stone had fractured to expose metal tubes filled with coloured threads and a low voice burbled endlessly from no particular source, its word blurred to the point where the meaning tantalised but could not be grasped.

“Body.” Hemmac sniffed.

Gorgoth tensed, his grip tightening on the glow-bar, anticipating the worst. He saw nothing ahead, smelled nothing, but Hemmac was never wrong. Two more turns and a hundred yards brought them to the ruin of a man, a desiccated corpse tucked up into the corner of the passage as if his last thoughts had been of a tidy death.

“Not one of us,” Hemmac said.

The corpse, ugly as it was, bore no deformity. An empty scabbard hung at the man’s belt and he wore a padded jerkin sewn with iron-plates. A soldier from the Red Castle perhaps. Occasionally someone would lose themselves beneath the cellars of Duke Gellethar’s castle high on the shoulder of Mount Honas, but Gorgoth had never known one wander so deep before death claimed them.

“Mine.” He pulled the knife from the man’s belt while Hemmac searched him for c

oin. A good piece of castle-forged steel was quite the prize. Gorgoth held the glow-bar aloft, eyes hunting for the missing sword.

When the dead man turned his head his neck creaked and dry skin fell away revealing darker meat beneath. Gorgoth backed away quickly, lip curling in a snarl of disgust.

“They came this way.” The dead man’s voice emerged as a rasping, like leather over stone. “The woman and two infants.” His lips split as they pulled back over yellow teeth. “The young ones would be good tributes.”

Gorgoth raised his foot to stamp the dead thing into silence, then lowered it with a sigh. When Chella had first led her necromancers to the mountain the leucrota had fought them. It had gone poorly. Gorgoth’s parents had negotiated the peace. The remnants of the tribe had not been a position to resist Chella’s terms.

Hemmac led on.

An hour later he paused again. “It’s bad ahead.”

Gorgoth could smell it now, the faintest sweet-sour hint. While a low level of the Builders’ toxins pervaded Mount Honas, in some places they ran in veins or mouldered in hidden caches. The leucrota could survive high concentrations for a short time but their bodies would twist further to accommodate the new poisons. If Alithea had taken her young sons into such a place their changes would come still faster and still more powerfully. His sister wouldn’t have done that though – she was desperate but not insane.

Five hundred yards later they found the source. The floor had given way in an area some five yards in length and crossing the width of the corridor. The glow bar revealed a corroded pipe wide enough for Gorgoth to stand in, unbowed at over seven foot tall. The shattered top portion lay mixed with rubble along the pipe’s bottom and through it all ran a virulent green trickle. The stink of poison curled Gorgoth’s nose hairs. It made his eyes sting and his skin itch.

The collapse looked fresh, and if Alithea had fallen in with it then she would not have been able to manage the climb out.

Prince of Fools

Prince of Fools Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State

Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State Holy Sister

Holy Sister The Liar's Key

The Liar's Key The Wheel of Osheim

The Wheel of Osheim Emperor of Thorns

Emperor of Thorns Red Sister

Red Sister Prince of Thorns

Prince of Thorns The Girl and the Stars

The Girl and the Stars Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times)

Dispel Illusion (Impossible Times) Road Brothers

Road Brothers Grey Sister

Grey Sister King of Thorns

King of Thorns The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original

The Visitor--Kill or Cure--A Tor.com Original The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus

The Broken Empire Trilogy Omnibus One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1)

One Word Kill (Impossible Times Book 1) King of Thorns be-2

King of Thorns be-2 Prince of Thorns tbe-1

Prince of Thorns tbe-1 Emperor of Thorns tbe-3

Emperor of Thorns tbe-3 Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

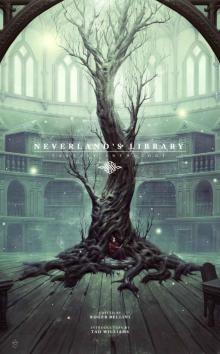

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3) Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology

Neverland's Library: Fantasy Anthology